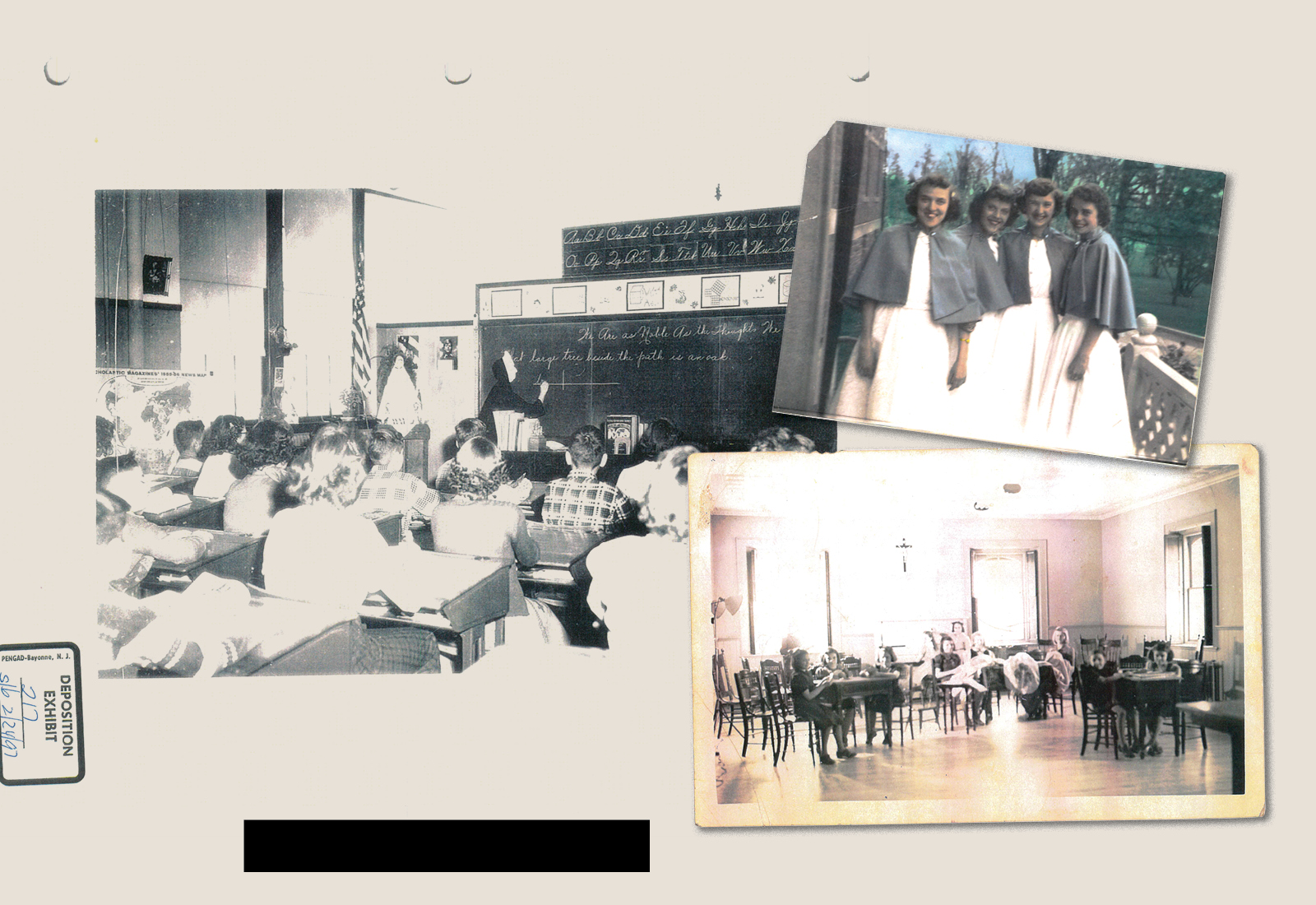

We Saw Nuns Kill Children: The Ghosts of St. Joseph's Catholic Orphanage

By

Christine Kenneally, Buzzfeed, Senior Contributor

Buzzfeednews.com

August 27, 2018

It was a late summer afternoon, Sally Dale recalled, when the boy was thrown through the fourth-floor window.

“He kind of hit, and— ” she placed both hands palm-down before her. Her right hand slapped down on the left, rebounded up a little, then landed again.

For just a moment, the room was still. “Bounced?” one of the many lawyers present asked. “Well, I guess you’d call it — it was a bounce,” she replied. “And then he laid still.”

Sally, who was speaking under oath, tried to explain it. She started again. “The first thing I saw was looking up, hearing the crash of the window, and then him going down, but my eyes were still glued—.” She pointed up at where the broken window would have been and then she pointed at her own face and drew circles around it. “That habit thing, whatever it is, that they wear, stuck out like a sore thumb.”

A nun was standing at the window, Sally said. She straightened her arms out in front of her. “But her hands were like that.”

There were only two people in the yard, she said: Sally herself and a nun who was escorting her. In a tone that was still completely bewildered, she recalled asking, Sister?

Sister took hold of Sally’s ear, turned her around, and walked her back to the other side of the yard. The nun told her she had a vivid imagination. We are going to have to do something about you, child.

The back of the now-closed St. Joseph’s Orphanage in Burlington, Vermont.

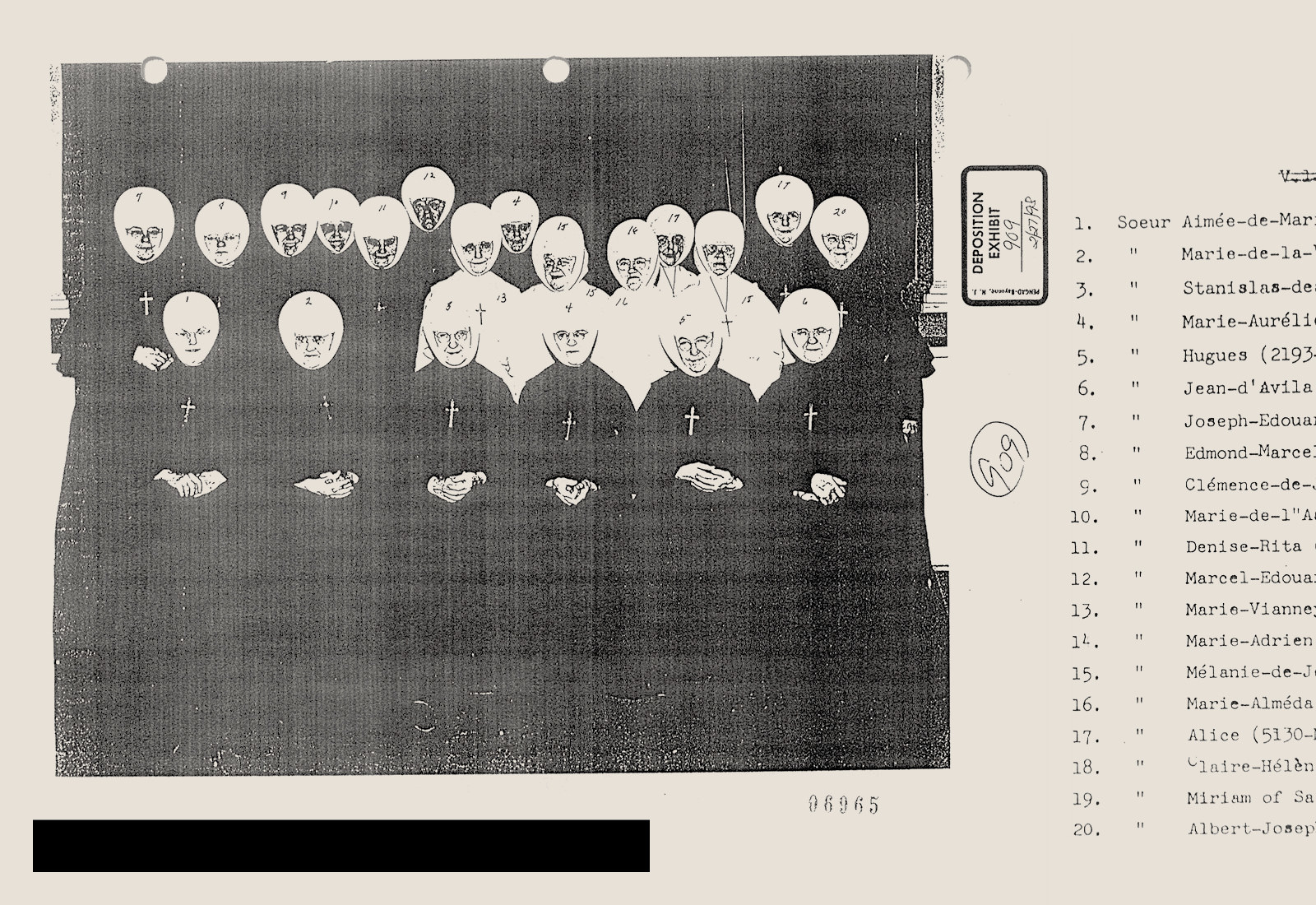

Sally figured the boy fell from the window in 1944 or so, because she was moving to the “big girls” dormitory that day. Girls usually moved when they were 6, though residents of St. Joseph’s Orphanage in Burlington, Vermont, did not always have a clear sense of their age — birthdays, like siblings and even names, being one of the many human attributes that were stripped from them when they passed through its doors. She recounted his fall in a deposition on Nov. 6, 1996, as part of a remarkable group of lawsuits that 28 former residents brought against the nuns, the diocese, and the social agency that oversaw the orphanage.

I watched the deposition — all 19 hours of grainy, scratchy videotape — more than two decades later. By that time sexual abuse scandals had ripped through the Catholic Church, shattering the silence that had for so long protected its secrets. It was easier for accusers in general to come forward, and easier for people to believe their stories, even if the stories sounded too awful to be true. Even if they had happened decades ago, when the accusers were only children. Even if the people they were accusing were pillars of the community.

But for all these revelations — including this month’s Pennsylvania grand jury report on how the church hid the crimes of hundreds of priests — a darker history, the one to which Sally’s story belongs, remains all but unknown. It is the history of unrelenting physical and psychological abuse of captive children. Across thousands of miles, across decades, the abuse took eerily similar forms: People who grew up in orphanages said they were made to kneel or stand for hours, sometimes with their arms straight out, sometimes holding their boots or some other item. They were forced to eat their own vomit. They were dangled upside down out windows, over wells, or in laundry chutes. Children were locked in cabinets, in closets, in attics, sometimes for days, sometimes so long they were forgotten. They were told their relatives didn’t want them, or they were permanently separated from their siblings. They were sexually abused. They were mutilated.

Darkest of all, it is a history of children who entered orphanages but did not leave them alive.

From former residents of America’s Catholic orphanage system, I had heard stories about these deaths — that they were not natural or even accidents, but were instead the inevitable consequence of the nuns’ brutality. Sally herself described witnessing at least two incidents in which she said a child at St. Joseph’s died or was outright murdered.

It’s likely that more than 5 million Americans passed through orphanages in the 20th century alone. At its peak in the 1930s, the American orphanage system included more than 1,600 institutions, partly supported with public funding but usually run by religious orders, including the Catholic Church.

Outside the United States, the orphanage system and the wreckage it produced has undergone substantial official scrutiny over the last two decades. In Canada, the UK, Germany, Ireland, and Australia, multiple formal government inquiries have subpoenaed records, taken witness testimony, and found, time and again, that children consigned to orphanages — in many cases, Catholic orphanages — were victims of severe abuse. A 1998 UK government inquiry, citing “exceptional depravity” at four homes run by the Christian Brothers order in Australia, heard that a boy was the object of a competition between the brothers to see who could rape him 100 times. The inquiries focused primarily on sexual abuse, not physical abuse or murder, but taken together, the reports showed almost limitless harm that was the result not just of individual cruelty but of systemic abuse.

In the United States, however, no such reckoning has taken place. Even today the stories of the orphanages are rarely told and barely heard, let alone recognized in any formal way by the government, the public, or the courts. The few times that orphanage abuse cases have been litigated in the US, the courts have remained, with a few exceptions, generally indifferent. Private settlements could be as little as a few thousand dollars. Government bodies have rarely pursued the allegations.

So in a journey that lasted four years, I went around the country, and even around the world, in search of the truth about this vast, unnarrated chapter of American experience. Eventually I focused on St. Joseph’s, where the former residents’ lawsuits had briefly forced the dark history into public view.

The former residents of St. Joseph’s told of being subjected to tortures — from the straightforwardly awful to the downright bizarre — that were occasionally administered as a special punishment but were often just a matter of course. Their tales were strikingly similar, each adding weight and credibility to the others. In these accounts, St. Joseph’s emerged as its own little universe, governed by a cruel logic, hidden behind brick walls just a few miles past the quaint streets of downtown Burlington.

When I first started looking, it seemed that all that remained of St. Joseph’s were deposition transcripts and the sharp, bitter memories of the few remaining survivors I was able to find. But over the course of years I found that there was far more to discover. More than the former residents themselves knew, and more than was uncovered during the 1990s legal battle. Through tens of thousands of pages of documents, some of them secret, as well as dozens of interviews, what I found at St. Joseph’s and other American orphanages was a vast and terrible matrix of corroboration.

The Diocese of Burlington, Vermont Catholic Charities, and the Sisters of Providence, the order of nuns who worked at St. Joseph’s, all chose not to speak with me about these allegations. At the end of my reporting, Monsignor John McDermott, of the Burlington Diocese, provided a brief statement: “Please know that the Diocese of Burlington treats allegations of child abuse seriously and procedures are in place for reporting to the proper authorities. While it cannot alter the past, the Diocese is doing everything it can to ensure children are protected.”

Sally Dale

For decades, Sally Dale, like so many of the children of St. Joseph’s, avoided speaking about what happened there. Many of the orphans went on to marry, and to have children and grandchildren, without letting on that they had spent any time in an orphanage. Some, their trust forever shattered, had been unable to forge any close connections. Robert Widman, the attorney who sat beside Sally, offered them a chance to be heard, and to force the world outside the orphanage to reckon with what went on inside its walls.

That legal effort lasted three years. It cost Widman’s law firm dearly, and it pushed him to the edge emotionally. Decades later, he described it as one of the most wrenching cases of his life.

For the former residents of St. Joseph’s — and for people in Albany and Kentucky and Montana who emerged from orphanages with similar stories — the fight was something much more. It was a chance most of them had never had before: to be heard, and maybe believed.

For the Catholic Church, too, the stakes were enormous. If the Burlington plaintiffs won, it could create a precedent and encourage civil cases at a massive scale. The financial consequences would be hard to fathom. Widman and his band of orphans posed a profound threat, and the church was going to bring all its might to oppose it.

Philip White was sitting in his large, third-floor law office one afternoon in 1993 when the mysterious caller arrived. He said his name was Joseph Barquin.

White invited him to have a seat and tell his story. Barquin asked White to send his secretary out so the two men could speak privately.

Barquin said he had recently married, and that his new wife had been shocked by the sight of terrible scars on his genitals.

Barquin told White what he had told her: that in the early 1950s, when he was a young boy, he had spent a few years in an orphanage called St. Joseph’s in Burlington, Vermont. It had been a dark and terrifying place run by an order of nuns called the Sisters of Providence. Barquin recalled a girl who was thrown down stairs, and he remembered the thin lines of blood that trickled out of her nose and ear afterward. He saw a little boy shaken into uncomprehending shock. He saw other children beaten over and over.

A nun at St. Joseph’s had dragged Barquin into an anteroom under the stairs and forcefully fondled him, and then she cut him with something very sharp. He didn’t know what it was; he just remembered that there was blood everywhere.

Barquin’s wife had encouraged him to go to therapy. To get help with the cost, and to get an apology, Barquin spoke to two priests at the diocese, but he received very little response. Now he wanted to sue.

He had come to the right lawyer. As a prosecutor in Newport, Vermont, and then as a private attorney, White had devoted his career to challenging and changing the prevailing wisdom about young victims of sexual abuse.

Before 1980, White told me, social services typically steered child abuse victims away from court, because the process was thought to be too traumatic for the children and the cases were too hard to prove. White maintained that the fear of trauma had more to do with the adults’ discomfort than with the actual needs of the children. So he and some of his colleagues brought together social services, police, and probation officers and created a new set of protocols for how abuse should be addressed. White and his colleagues traveled around the state, and eventually the country, encouraging different agencies to work together, and educating mental health workers and teachers about how and why to report abuse. When prosecutors said they didn’t go after child sexual abuse because they couldn’t face the guilt of losing, White would reply, “If you don’t bring the case, how can you sleep?”

White’s team developed a way for children to testify on closed-circuit TV so they wouldn’t have to tell their story in front of their abuser. Whenever a young client testified, White threw a party, with cake and balloons and streamers. He told the children that regardless of how the case was decided, they had spoken their truth, and that was the victory.

When bearing witness to the most disturbing experiences of Vermont’s children became too much, White would find the steepest ski slope and fly down, screaming his head off all the way, until he felt calm enough to return to his work.

For all the cases he had worked on, however, he had never heard a story quite like Barquin’s.

He knew from experience what it was like to challenge the diocese. Barquin’s assault had taken place decades ago, which would make it hard for White to find corroboration — and easy for the church to question Barquin’s memory. And as hard as it would still have been, in that era, to convince jurors that a priest could be a sexual predator, making that argument about a nun was going to be much harder.

Still, White decided to take Barquin’s case. He lodged a complaint in the US District Court at Brattleboro, Vermont, on June 7, 1993, seeking damages for Barquin’s injuries from physical, psychological, and sexual abuse at St. Joseph’s Orphanage 40 years before. The defendants he named were the Burlington Diocese, Vermont Catholic Charities, the orphanage, and, because Barquin didn’t know the name of the nun who abused him, Mother Jane Doe.

The diocese was represented by Bill O’Brien, a lawyer who worked for the church, as had his father before him. O’Brien noted that according to Vermont’s statute of limitations, adults who were abused as children have six years from the moment they realize they were damaged by the abuse to bring suit. Barquin had had 40 years to work out what had caused his injuries, O’Brien said, during which time relevant evidence or witnesses may have been lost. In a long memo to the judge, the church’s lawyers lectured White on points of law, quoting an opinion from a medical malpractice suit that said “the law is not designed to aid the slothful in evading the results of their own negligence.”

White arranged a press conference for Barquin to tell his story, in hopes it might bring other St. Joseph’s survivors out into the open.

In his years since leaving the orphanage, Barquin had led an adventurous life. He had worked as a diver, unearthing old shipwrecks and ancient fossils. He had spent time at the famous Naropa Institute in Colorado, hanging out with Ram Dass and Allen Ginsberg. He’d even led dolphin encounters. But the day of his press conference, Barquin felt like he was lighting a match inside a dark and ominous cave. He was scared, but hopeful that he might inspire others to do the same.

White hoped he might hear from a few more former St. Joseph’s residents. He heard from 40. Soon a support group called the Survivors of St. Joseph’s Orphanage and Friends formed. Participants said it grew to 80 members.

The meetings were unpredictable. Some former residents said that the orphanage was the best thing that ever happened to them. Others recounted constant cruelty and physical abuse. Some threatened violence against clergy members. One woman said she was writing a book. Another, who had been at the orphanage in the 1920s, called to tell her story, weeping in fear that God would punish her for saying it aloud. One man turned up outrageously drunk. Another spoke about how, at home, he would regularly lock himself in a box. Someone wrote to White to warn him that the diocese had sent a spy.

Around that time, one former resident killed himself. Survivors fought among themselves about what strategy to pursue. At one meeting, a woman was shouted down when she suggested that they all contact the bishop together. Some wanted therapists present at the meetings, but others were appalled by the suggestion.

Eventually White decided to convene a big gathering at the Hampton Inn in Colchester, Vermont, on the weekend of Sept. 18, 1994.

Sally Dale received an invitation. It said the event was a reunion for “survivors” of St. Joseph’s, which struck Sally as an odd word to use. She hadn’t been in touch with people from the orphanage for a long time, and she thought about it as little as possible. But she was curious to see some of the old faces and find out who was still around.

She was only a few steps inside the conference room when a man exclaimed, “You little devil!”

It was Roger Barber, one of the boys from St. Joseph’s, who was there with his two sisters. Little devil: That’s what they used to call her. She hadn’t thought of it in so long.

“Sal, you look good for everything you went through,” one of Barber’s sisters said.

“You were our Shirley Temple of the orphanage!” said the other. She reminisced about the way Sally sang “God Bless America” and “On the Good Ship Lollipop” when she was little.

Sally remembered some of those things. She sometimes remembered bad things too, such as times when the nuns hit her. But it was a long time ago. She recognized few of the 50 or 60 people in attendance. Little Debbie Hazen was there, and so was Katelin Hoffman, along with Coralyn Guidry and Sally Miller. Some of the women recognized each other not by name but by number: Thirty-two! Fourteen!

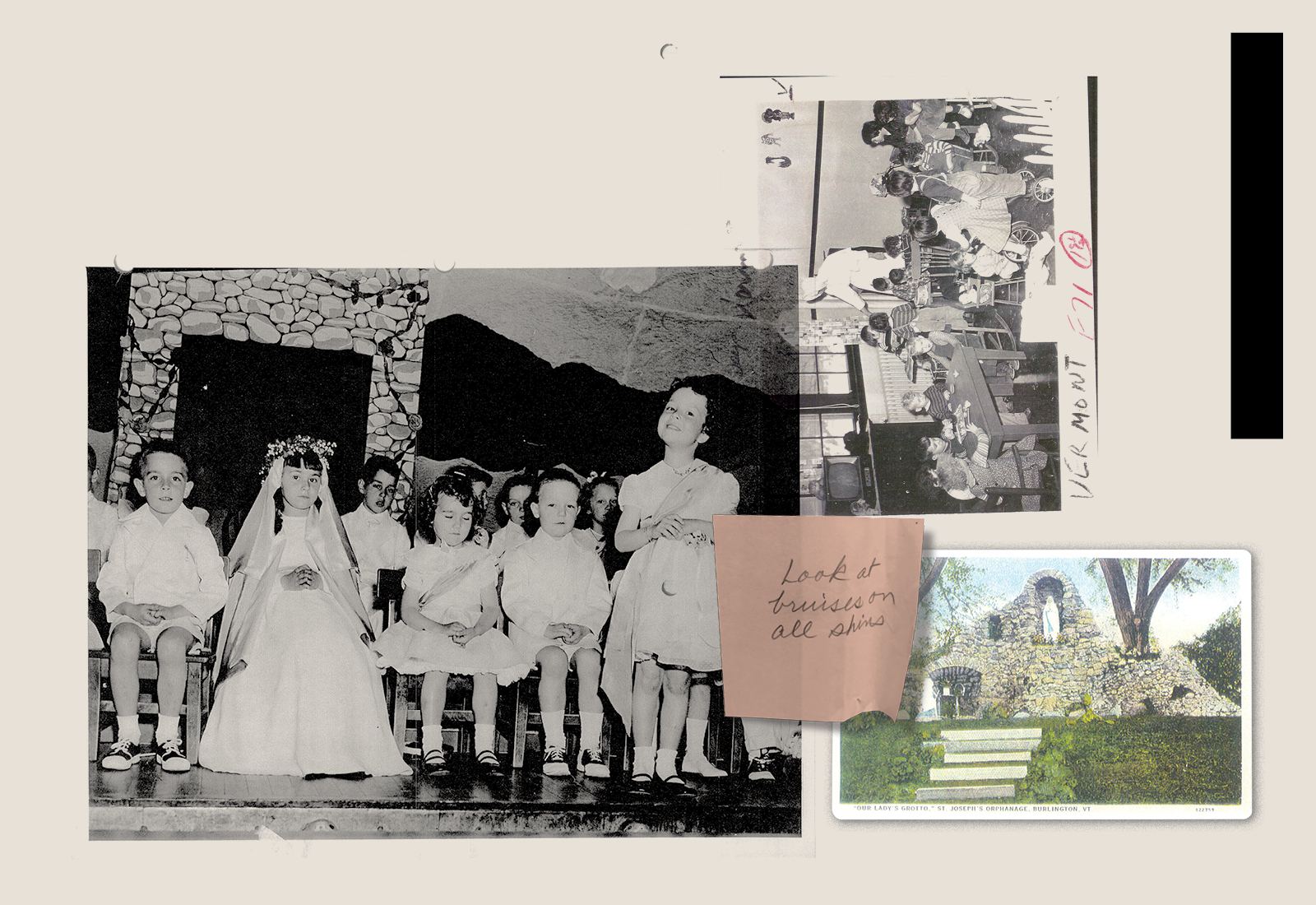

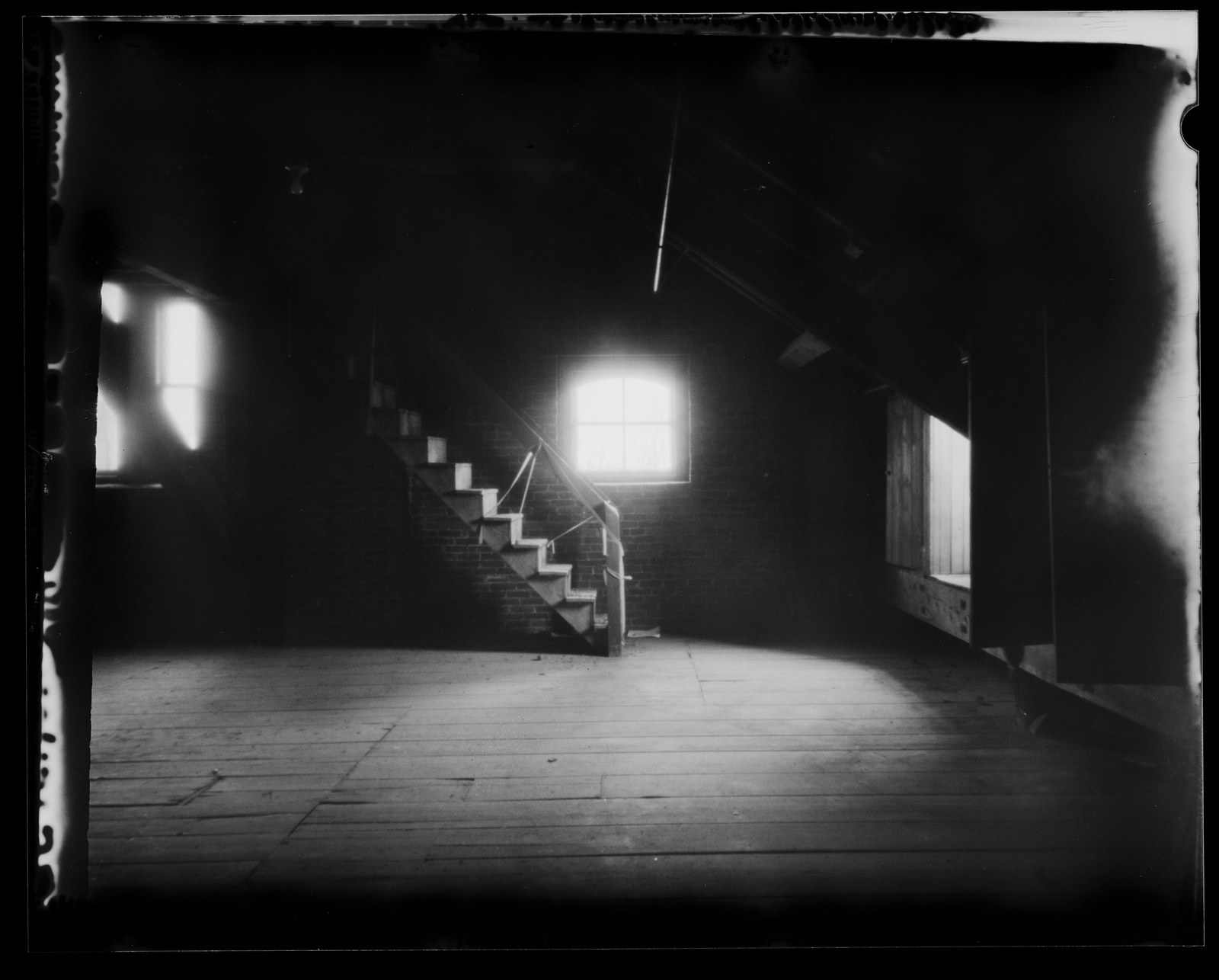

Details in the attic of St. Joseph’s Orphanage.

White began the day by introducing Barquin and some other people who were there to help. A man spoke about the Bible and turning to God in times like these, and two therapists said they were available for anyone who wanted to talk. Local journalists were on hand too.

Then Barquin told everyone about the nun taking him into the closet. Roger Barber spoke next. Sally remembered him saying that a nun told a group of older boys to rape him. As the stories tumbled out, former residents melted down in the meeting room and in the hotel’s hallways. A lanky, weathered man stood up and addressed another man before the whole crowd. I’m here because back in the orphanage I bullied you, he said. I felt bad about that all of my life. I just want to say I’m sorry. Then one woman spoke about how nuns wiped her face in her own vomit, and Sally started to remember that the same thing had happened to her. She could hear the voice of one sister telling her, after she threw up her food, You will not be this stubborn! You will sit and you will eat it.

A woman said she’d watched a nun hold a baby by its ankles and swing its head against a table until it stopped crying. As Sally listened to the awful stories, something ruptured inside her. She shook her head and began to say, “No, no, no, no, no, it’s not true.” But the memories were already flooding back.

Though the reunion was a two-day event, Sally left that first afternoon with a crushing headache. The next morning she had diarrhea and was unable to speak without heaving. She spent that night sitting bolt upright, remembering things she hadn’t thought about for decades, and saying, “No, no, no, no, no.” When her husband asked her why she was saying “no,” she just replied, “No.”

The old girls dormitory of the now-closed St. Joseph’s Orphanage in Burlington, Vermont.

South of Lone Rock Point, where North Avenue runs high above the eastern shore of Lake Champlain, beyond the winding paths that meander through the cemetery, behind the heavy doors of the large redbrick building, Sally was back in the orphanage. Probably not yet 6 years old, she was being marched toward the sewing room, compelled by a furious nun.

Sally had been caught running and giggling in the dormitory. The nun, Sister Jane of the Rosary, was known for her constant companion: a thick razor strap that the girls called “the green pill,” bitter medicine for any child who came near it.

Sister Jane of the Rosary took Sally to the little bedroom off the sewing room and made her lie facedown, dress yanked up, panties pulled down. Then the nun sent in Eva, a seamstress, who along with another lay employee, Irene, was one of the only two people that Sally felt safe with.

Eva came into the little room, looked at Sally — face down, dress up, defenseless — and stood frozen for a few long moments. The strap lay beside her on the bed. Then she left. Irene came in next, but she couldn’t do anything, either. Even Sister Jane of the Rosary, usually so quick to punish, came in but did nothing.

At last Sally heard Sister James Mary announce that she had “no problem” performing the task. Entering the room, she brought the strap down hard on Sally, from the back of her neck all the way down to her ankles. Once, twice. Ten times. Too many times to count.

Sally recoiled with each downstroke, but she tried her best to hold back the tears. The silence only enraged Sister James Mary, who kept hitting her. On and on, the blows kept coming. “You will cry!” the nun insisted.

Eventually Sally did. She began to weep.

Sally couldn’t twist around far enough to see the damage. But when Irene looked, she gasped.

“How many times do we have to tell you?” Sister Jane of the Rosary demanded from above. “If you cry, you cry alone. If you smile, the whole world smiles with you.”

Irene brought Sally across the long hallway, down the marble stairs, past the foyer, and into the office of the mother superior herself. Irene showed her Sally’s wounds. It wasn’t right to do that to a little girl.

Mother Superior replied that Sally was going to end up in reform school anyway.

The next time Sally was sent to Irene and Eva for a beating, Irene said she would deal with the child herself.

Irene hit her, but only on her bottom. Sally was so overwhelmed with gratitude that the next day, she told Irene that she loved her.

As the Burlington survivors group gained momentum, Joseph Barquin emerged as an extraordinary force for change. A judge had allowed his sexual assault case to go forward, and he was proving himself to be a tenacious litigant, rallying others to the cause and even doing his own investigative work. He visited a number of Sisters of Providence nuns at the local motherhouse, interviewing them on tape: “Who was the sister that was a real disciplinarian?” But his outsize role and expectations complicated matters. Having been the first to come forward, he believed that his ideas should carry extra weight. His relationship with White deteriorated over what Barquin perceived to be a lack of respect. Relations with the group frayed as well. Eventually a delegate said several members felt threatened by Barquin.

White came to the painful conclusion that he could not continue to represent Barquin and encouraged him to find new counsel. White planned to focus on the claims of the other former residents. But as all that was going on, White’s doctor told him that he had adult-onset diabetes. He had two children, one of them newborn, and it became clear that his firm was too small to provide all the resources needed to handle all the cases coming his way. White realized that if he was going to represent the orphans with integrity and competence, he would have to sacrifice everything else. “I’d basically have to leave my family, find a miracle drug for my diabetes, and find a new law firm,” he said later.

Around the same time, the bishop made a formal offer: $5,000 per person, in exchange for which the recipients would waive their right to further legal action.

White hated to see the cases end like that, but he knew that the statute of limitations would have prevented some of the plaintiffs from ever getting their day in court. And for many of them, $5,000 was serious money. He told his clients that he could not advise them what path to choose, but if anyone wanted to settle, he would help.

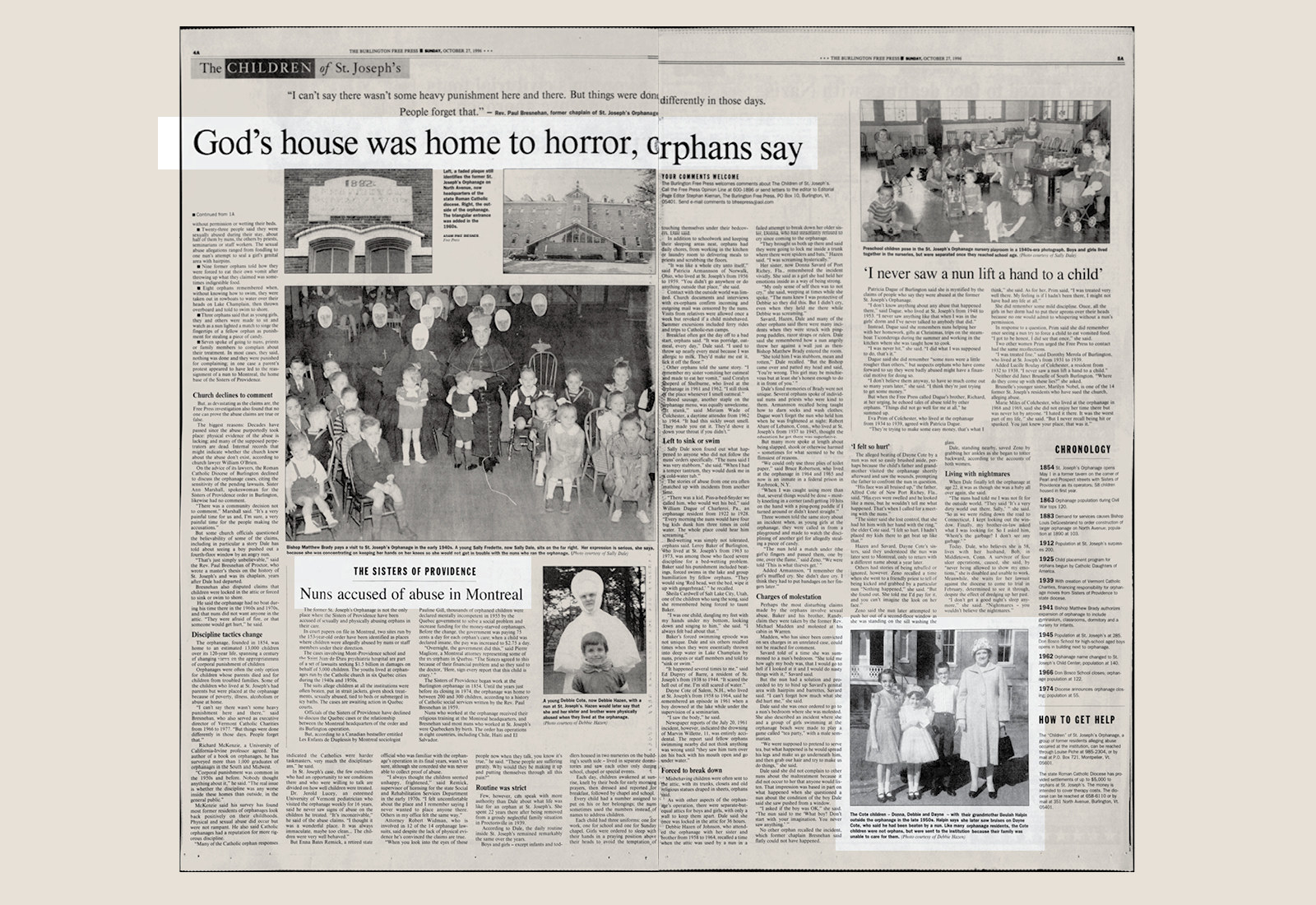

The Burlington Free Press reported that according to church officials, 100 people accepted the payment, for abuse they said they suffered. Plaintiffs said as many as 160 individuals, who had been at the orphanage from the 1930s to the 1970s, pursued the bishop’s offer.

For every one of those he represented, White sent a letter to Bill O’Brien, the church’s attorney.

“Dear Bill,” one of the letters said, “K remembers that Sister Madeline and Sister Claire … slapped her head and face, pulled her hair, struck her face with the backs of their hands, so that their rings split her lips, and tripped her and knocked her down.“

“Dear Bill … To this day, C will not enter a closet if it has a hanging light.”

“Dear Bill … If L was caught not paying attention, the nuns would take a needle and regularly prick his fingertips.”

“Dear Bill … The nuns would also force G and other children to hold their arms up at their sides, with their palms up in the air, balancing a book on the palms. If G dropped his arms before the requisite time was up, he would be beaten and forced to repeat the punishment all over again.”

The bishop published a letter around the same time. In a larger sense they were all victims, he said: children who had been abused, as well as the good priests and brothers and nuns. “If anyone has been hurt by any church official in anyway,” he wrote, “I am heartily sorry.”

Sally Miller, the woman who had suggested contacting the bishop at one of White’s survivors meetings, went ahead and visited him herself. She said he told her that if modern-day laws had been in place when he was a child, his own father would have been charged with child abuse, and yet he had got over what had happened to him. He didn’t understand why other people couldn’t get over what had happened to them.

They were just kids, Miller later testified that she told him.

Well, these nuns were just frustrated ladies, she said he replied. They didn’t have children of their own, and they didn’t know how to handle them.

Retired lawyer Robert Widman at his house in Burnsville, North Carolina.

Joseph Barquin contacted Robert Widman, a well-regarded lawyer near where he lived in Sarasota, Florida, whom he’d heard of from a friend of a friend. Much like Philip White, Widman didn’t immediately form an opinion as to whether Barquin was telling the truth, but he thought it was worth exploring further.

Widman decided that he would go to Burlington, Vermont, and with Barquin’s help, he would talk to as many of the former residents of St. Joseph’s as he could. He gave himself a few weeks to try to get to the bottom of what had happened.

The two men toured Vermont in early 1996 and Widman met with the survivors of St. Joseph’s in houses and homeless shelters and rustic B&Bs, and he had searing encounters in the most bucolic settings.

The more people he spoke to, the starker the patterns that emerged. People who had been at St. Joseph’s in different years, even different decades, described how they had been confined in the same water tank or how they had watched other children be put into the same nursery closet. They remembered a ruler, a paddle, a strap, a small ax, a light bulb, clappers, and a set of large rosary beads. They spoke about lit matches being held against skin. They described a cavernous attic. When they were good, they had gone up there two-by-two to retrieve Sunday clothes, play clothes, and winter gear. When they were bad, they were pushed, dragged, and blasted up the stairs to sit alone and scream into the void.

Details within St. Joseph’s Orphanage.

The aftershocks of the orphanage reverberated through their entire lives. Many of the people Widman met had spent time in jail or struggled with addiction, facts that a defense lawyer could use to discredit them in front of a jury. He wanted to help them, but he wasn’t sure if he should take on the enormous job. Not until the day he made the four-hour drive to Middletown, Connecticut, to meet Sally Dale.

Sally took him in through a mudroom with lots of tiny boots flung about, to a kitchen filled with the inviting smell of cooking. They sat down at the table and ended up speaking for hours.

Then, and in subsequent conversations, she told him about the little boy who was thrown out of a fourth-story window by a nun. She told him about a day when the nuns sent her into the fire pit to retrieve a ball and her snow pants caught on fire, and about how weeks later, as the nuns pulled blackened skin off her arms and her legs with tweezers and she cried out in pain, they told her it was happening because she was a real bad girl. She told Widman about a boy who went under the surface of Lake Champlain and did not come up again, and a very sad and very frightening story of a little boy who was electrocuted, whom the nuns made her kiss in his coffin.

When Widman walked out of her house that day, he stood in her driveway with tears in his eyes. He couldn’t quite say what it was about Sally — her strange fearless innocence, her stubbornness — but he trusted every word she said. She “was the most believable person I’ve met in my life,” he later told me.

Widman asked Sally to write down what she remembered. He told her that he didn’t care about spelling or anything like that, he just hoped it might help her sort things out. She liked the idea, and over many months, she sent him a series of powerful and detailed letters.

July 12, 1996

I had a dream last night about the orphanage. But the funny part is my eyes were wide open. I saw a sister come into the girls small dorm and she came over to my bed and told me to come with her. She took me by the hand and brought me to her room. She put me on her bed and started to touch me all over, I was so afraid but would not make a sound so she would get mad and [unclear] me. Then she took my hands and told me to rub her all over while she put her fingers were it really hurt and I did not like it. Then she told me to put her fingers were she had touch me on her and I said no.

She got so mad that she gave me a strapping real hard and sent me back to my bed in the dorm and told me to never say anything about it, so I did what she sayed because I really was afraid she would hurt me again.

1996

I remember when I was real little and would get mad I would throw a temper tantrum. They would get so mad at me they would grab me wherever they could and bring me into the bathroom and put me on my back over the tub and pour cold water into my face until I would stop scream and kicking. The water would come down so hard on me.

1996

As I really got older they used to make me babysit the real little ones in the nursery. There were times when I would see things the nuns were doing to them but did not know where to go to tell someone. Sometimes I would ask them why they did those things and they would say because they were very bad boys or girls.

In the winter we would have these funny looking things that heat and steam would come out off. They would put the little kids on them sometimes just to sit but others they would stand them on it and then push them and of course sometimes there little legs would get caught between the wall and radiator and the little kids would really scream and cry. They would pull them out and some kids would have real nasty burns and blisters from it. If they did not stop crying they would then lock them in the same closet they used to put me in. You could here them but you could do nothing for them because they would keep the keys on them till they were ready to let them out. But what could I do I was still just a kid myself. Boy sometimes I would pray that either we would get killed or they would but it never happened. I really believed that nobody even God did not love any of us and that we would have to stay there forever.

One by one, in their homes, or at the offices of the Burlington law firm Langrock Sperry & Wool, Widman sat down with the survivors who had not yet settled and told them that he would represent them — but that it would be a risky, difficult business. Church lawyers would ask the most painful questions possible. If plaintiffs had ever visited a psychologist or psychiatrist, the lawyers could demand to see their files. If they were divorced, the church would want to talk to their exes and their children. And after all that, there was no guarantee that they would win.

He threw himself into the discovery process. He learned fast, but the more he heard, the more questions he had. How had St. Joseph’s been run? Who had lived there? Where had they come from? How did money flow through the place? And one of the hardest things to understand: How could atrocities and happiness exist in the same place? Even residents who spoke about extreme abuse also laughed about sliding down bannisters, appreciated learning how to sew, or expressed pride about starring in an orphanage play.

A woman called Marilyn Noble gave Widman the manuscript for a memoir called Orphan Girl No. 58. Noble lived at St. Joseph’s at the same time as Sally Dale. As a girl, she had been forced to slap herself 50 times in the face, and when she didn’t do it hard enough, a nun did it for her. When a cut under her fingernail developed into a throbbing, toxic infection, she had been too afraid to tell the nuns until it was almost too late. But she still cherished the memory of when the von Trapps, the Austrian family whose flight from the Nazis inspired The Sound of Music, came to visit St. Joseph’s. For the singing of the benediction, Noble was placed next to Maria herself. The kindest and most beloved stepmother in the world leaned down and told Noble that she sang beautifully.

Even basic information about how orphanages operated was hard to find. Widman located no books or studies on the subject. What little press coverage the institutions had received over the course of the century was usually about jolly excursions or the happy recovery of a runaway scamp.

The more Widman spoke to people who had lived at St. Joseph’s, which had been founded in the mid-1800s, the clearer it became that the hole in the public record was not an accident. Thousands of people all over the United States had at some time worked in an orphanage, yet none had come forward to reminisce about their time, at least not anywhere that Widman could find. The diocesan hierarchy had oversight of the orphanage, and the nuns had lived and worked there, but none of them were forthcoming with their recollections.

It was the same with the children. Siblings who had once been in the same orphanage together had often not discussed it with each other, much less with friends or even spouses.

The loft above the attic of the now-closed St. Joseph’s Orphanage.

In the earliest days of the orphanage, it had housed the aged as well as the young. One woman recalled lying in bed at night, as a child, listening to old souls trudge up and down the long hallways making “screaming and moaning and scraping sounds.” She realized only later that the terrifying sounds came from old folks pushing a chair in front of them, like a walker. Eventually, the elderly residents left.

The children remained. Hundreds of them. As Widman came to see, however, many of them were not actually orphans.

They had been born into local families, Catholic French Canadians but also English or Irish Americans and in a few cases African Americans or Abenaki, Native Americans of the region.

Most were extremely poor. One girl had milk for the first time at St. Joseph’s and thought it was the most delicious thing she had ever tasted. One girl had seen an egg at the dining table only a few times a year. But lack of money was usually just one of their problems.

The children’s parents were often ill or addicted, jailed or divorced, or bullying, monstrous, or violent. Some parents delivered their own children to the nuns, believing they were leaving them in a safe place. Many were brought by the state, after their homes were deemed unacceptable. Sometimes they ended up in an orphanage simply because their mother was unmarried. They arrived in every imaginable condition, dirty and lice-ridden, covered in bruises, recently raped, or perfectly healthy. No matter where they had come from, many of the children didn’t know where they were going until the moment they turned around and discovered that whoever had brought them there was gone.

Once the doors of St. Joseph’s had shut behind them, the children played a part in a strange, private theater, with many actors but no audience. They even took on different identities, as the nuns addressed them by number, not by name. The women of the Sisters of Providence had been renamed, too, when they joined the order and took their vows. Leonille Racicot became Sister James Mary. Jeanne Campbell became Sister Jane of the Rosary. Marie-Rose Dalpe became Sister Mary Vianney. And various men moved in and out of the drama: priests, seminarians, counselors, and others, recurring characters who kept their given names and who would appear for a time, then step back offstage and into the rest of the world.

In 1994, members of the survivors group asked for permission to return to the old brick building, which had stopped admitting children back in the 1970s and now housed only a few church offices. Initially they were turned away at the door. Months later some were allowed to walk through, but usually just one at a time. The diocese reached out to one former resident, whom they believed would testify for them, and flew her in from Utah for a tour. She told me they said they didn’t want plaintiffs in the building because “it would cause false beliefs” and “they could make up things by going through it.” Walking down the long hallways and standing in the empty dorms, the woman found, brought back many vivid memories.

Widman wanted to get in too, but he knew the diocese would be even less likely to arrange a tour for him than for the building’s former residents. So one day he just walked in the front door, said he was visiting from out of town, and politely asked if he could look around. The person at reception told him to go ahead.

The new elevator in the orphanage.

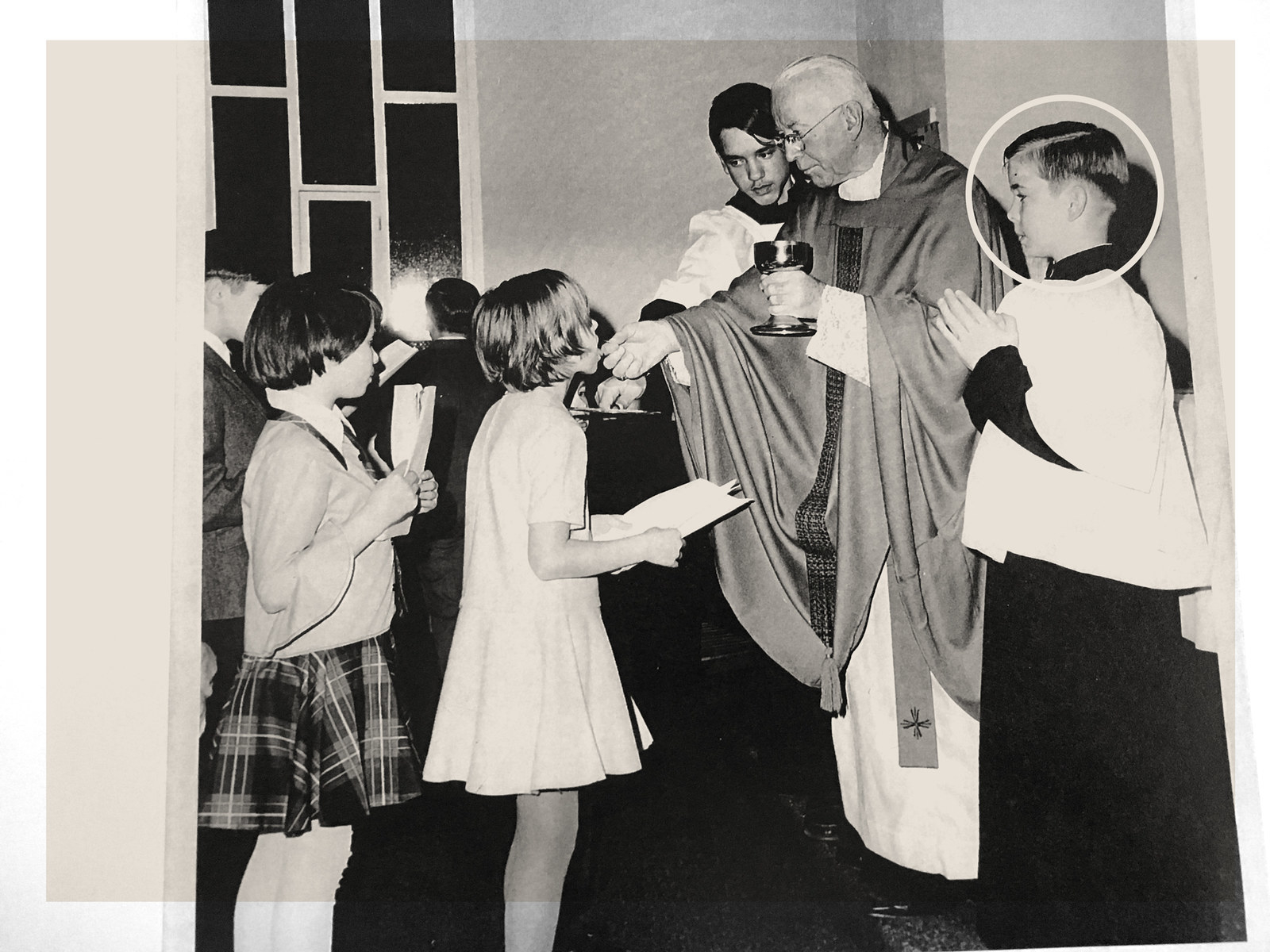

The grand, marble, circular staircase, up which children had trudged, and down which some had fallen or been thrown, was removed in the 1960s to accommodate an elevator, an innovation that was exciting enough to warrant a newspaper article, bearing a photograph with a spectacled, smiling nun and grinning, well-dressed children.

The replacement staircase, now old and chipped, was narrow and utilitarian. Widman followed it straight up to the top floor.

Stepping through the oddly small door to the attic was like stepping into a different universe.

Several orphans had told him it was a terrifying place inhabited by scurrying mice and the occasional bat, along with sheet-draped statues that seemed to come to life when the wind blew through. Sally had told him about an electric chair — or something that looked just like one — that a nun used to strap her into for hours, taunting her that the chair would fry her.

Even for an adult, the shadowy chamber was immense and disorienting. Widman gazed at the rafters and the loft and the door that concealed the spiral staircase to the cupola. Names had been scratched in the wood of the doorframe.

Widman found a huge metal water tank with pipes coming out of it. It had a big lid, and as he stood there and looked at it, he remembered that Sally Dale had told him that nuns made her climb up the little ladder and drop herself in. Then they pulled the lid back over and left.

Jack Sartore

Sally Dale’s case was filed in the US District Court of Vermont on June 13, 1996. Widman always went with the best case first. Along with his partner, Geoff Morris, and the local firm Langrock Sperry & Wool, he took 25 cases before two different courts. The first 12 new cases, including all the out-of-state plaintiffs, went to federal court. The other 13 went to state court. “We didn’t want to have our eggs in one basket,” Widman told me. Other St. Joseph’s cases cropped up, too, as a few more orphans launched suits with different attorneys.

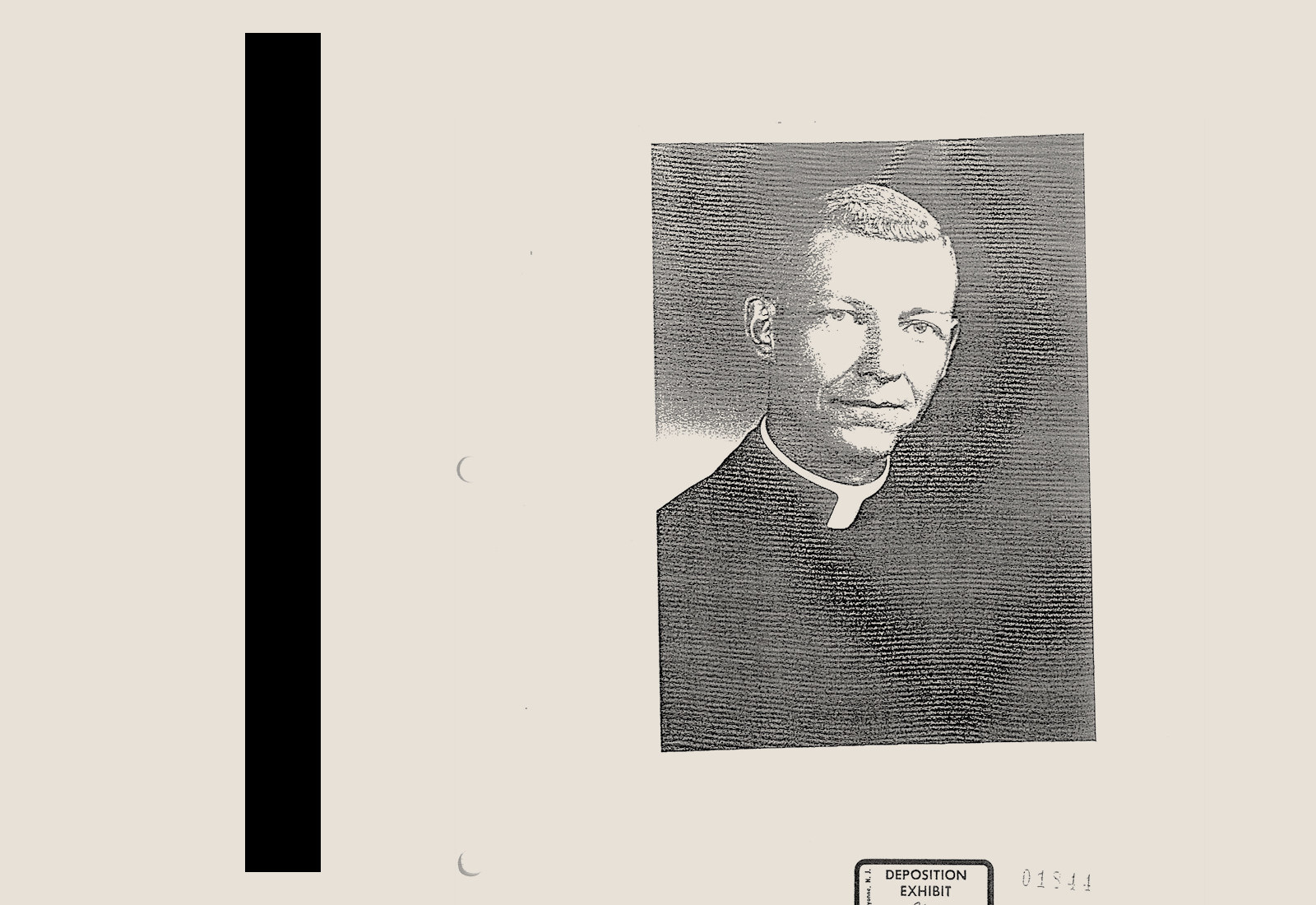

Widman’s lawsuits named three defendants: the Roman Catholic Diocese of Burlington, Vermont, represented by Bill O’Brien; Vermont Catholic Charities, represented by John Gravel; and the Sisters of Providence, who hired Jack Sartore, a litigator with a reputation for being uncompromising. One attorney told me that local lawyers referred to him as Darth Vader.

Traveling back and forth from Florida for a week or two at a time, Widman drove through Vermont in search of St. Joseph’s alumni who might join the plaintiffs or serve as witnesses. One person would lead him to five more, and those five would lead to another 25. And the more stories that Widman gathered, the more they began to knit themselves together, as happened in the case of the girl who stole a piece of candy.

A number of women separately told Widman they remembered a day when they were gathered together to witness a punishment. One thought it happened near the girls dining room. Another thought it was in the room where the children took off their coats and hats. Everyone agreed it happened downstairs.

Three women recalled that a girl was placed facedown over a desk and beaten. Two remembered that the nun used a paddle. One recalled that the nun had started out hitting the girl with a piece of wood 2 or 3 feet long, but it broke, and that’s when she reached for the paddle. Eventually the handle of the paddle snapped, so she got another paddle and used that one until she was finished. “You could always tell when they were done,” one woman explained, “because the last one was the hardest.”

All the women remembered that the nun pulled out some matches. One woman thought the nun had a whole box of them. Another remembered only a single stick. One thought the nun said, “I am going to show that I don’t tolerate stealing in here.” Another remembered it as, “This is what happens to people who steal.” A third thought the nun said, “This is what happens when you do things like this.” But they all remembered that the match was lit and the girl was held.

One recalled that the girl had struggled and cried; another remembered that all the girls cried; one believed that she herself had spoken out, but that no one else said a word. Still, they all remembered what happened next.

“She lit the match and she held her hand right over the match, and her hand was touching the flames, and I sat there and I cried and I told them to stop,” one said. The nun “took matches out of her dress and she burned the tips of each one of her fingers,” recalled another. The woman said the girl, weeping, confessed to taking the candy and said she wouldn’t do it again.

If the children mentioned the incident, one witness remembered a nun saying, they would never see their parents again.

Piecing together some background details, Widman figured that the girl’s name was Elaine Benoit. He was desperate to find her, but none of his searches yielded anything. Until one day he got a call.

I’m Bob Widman, what can I do for you?

His caller asked him if he was looking for Elaine Benoit.

Yeah, I’m looking real hard.

Well, I’m Elaine, the woman said.

Widman was stunned. I’ve heard this story… he began.

About the burning? she said. That was me. Then she told Widman her story. It was just as everyone had said.

The women’s stories about the candy thief provided Widman a lesson in how traumatic memory can work. The witnesses remembered that the girl had stolen some candy, and they all remembered that a nun caught her. Three of them remembered the name of the girl correctly, and although there was no consensus on the nun’s identity, most of them remembered that one nun administered the punishment. Specific details diverged, but the story’s center held.

Often, traumatic memory worked just like normal memory, meaning that an episode might blur over time. For some people, the more intense an experience had been, the likelier they were to retain it as a vivid narrative. But there was a threshold, at least for some. If an experience was too disturbing, it sometimes vanished. Whether the experience was actively repressed or just forgotten, it seemed to disappear from consciousness for decades, returning only in response to a specific trigger, such as driving by an orphanage or seeing a nun at the supermarket.

After each interview, Widman took notes on who he met, what had happened to them, and who they named. Inside his bursting binder was not just a list of events or a big picture; it was a whole world that had spun quietly for decades on the edge of a small and oblivious community. Every story that Widman gathered was a kind of proof of concept for every other. It might be hard for someone to believe that a child at St. Joseph’s was punched in the face — until you heard that another child was held upside down out a window and yet another was tied to a bed with no mattress and beaten. It strained credulity to think that a nun would hold a child’s head underwater, until you also heard about the nuns who covered babies’ mouths until they turned blue.

A pinhole photograph of the attic at St. Joseph’s Orphanage.

Around three years after Joseph Barquin’s suit was first filed, the diocese agreed to resolve it through mediation rather than a trial in open court. Widman wasn’t surprised. In the relatively short amount of time that he had known Barquin, he had watched with fascination as his client became an intense irritant clamped tight to the church’s side. Emerging from a lifetime of silence and fear, Barquin was compelling in front of a microphone. And he had been a powerful leader, at least until relations deteriorated. He had inspired many reluctant former residents to join him in speaking out.

The mediation was not an easy process, and there were a few false starts. In the end, Barquin said, the church settled for a significant amount of money — and a provision that the agreement and the amount be kept secret. (I was unable to obtain any of the documentation for the settlement.)

In his final meeting with the chancellor of the diocese, Barquin recalled, he and the chancellor asked their attorneys to leave the room, and with only a mediator present, they hashed out the details of the settlement. Both men wept.

Barquin’s sense of reconciliation with the giant institution proved to be a powerful one. He reversed course and started contacting Widman’s other plaintiffs, trying to persuade them to abandon their legal counsel.

In an interview with the Burlington Free Press, Barquin said that he wanted to find a non-adversarial way for his fellow orphans to resolve their claims. “Rage and anger is never going to work for the future of these people,” he told the reporter. Barquin began to phone Sally Dale to suggest that he could have the bishop and some nuns drop by her house to talk about things. Dale, who was horrified by the suggestion, said no.

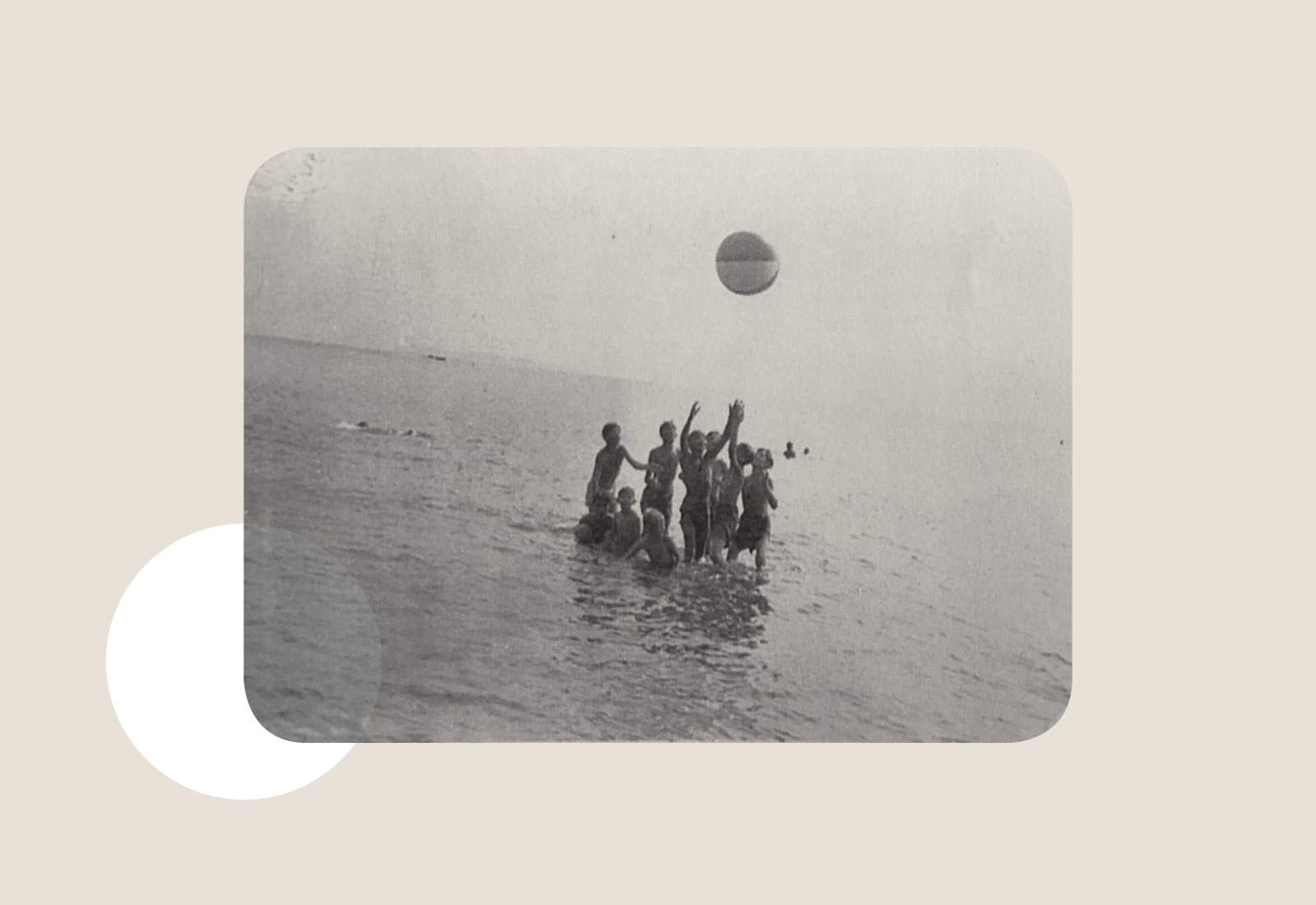

Sally was back in the orphanage. It was a summer day, and the girls had gone down a huge green hill and through a field of lilac bushes, scattered wildflowers, and floating cottonwood that went right up to the edge of a thick oak forest. They plunged in, following a steep, winding path, crossing over a railway track, and continuing down through the trees until the forest stopped so abruptly that when they came out the other side of it, it was like they had walked through a solid green wall.

There in front of them was North Beach, where the water was clear and lovely and shallow, with tiny little fish darting around as the girls chased each other.

As she waded in the shallows, Sally saw two nuns and a boy in a rowboat head out to where the water was deep.

Sally had been taken out in that boat too, as had many other children, and she knew what came next: The nuns threw you in the water. They said it taught you how to swim. When it was her turn, Sally had discovered she was in fact a strong swimmer, making her way back to the beach on her own with some pride.

But the boy in the boat was screaming. Sally watched as the nuns threw him in, then she waited and wondered what had happened to him. When the children trudged back up the hill, Sally asked a nun if the boy had drowned.

Oh, don’t worry, the nun said. He’s gone home for good.

There were other mysterious disappearances, such as the little girl whom a nun had pushed down the stairs. Irene, one of the lay employees, told Sally to keep the girl awake and get her to talk, but the little girl just moaned. She had a huge bump coming up on her forehead and big, dark bruises around her eyes.

Sally helped Irene take her to the hospital. Someone took the girl from them. Oh, another mishap? Another accident-prone...? someone there said.

Later, Sally asked the nuns if the girl was okay, and they told her the same thing she had heard about the others: The girl’s family had taken her home for good. Sally didn’t dare ask any more questions.

She also didn’t ask questions about Mary Clark, her favorite little girl from the orphanage’s nursery.

The nuns who worked there hated the sound of crying. Mary didn’t cry, however. She just made tearless little sobbing sounds, and the nuns hated that most of all.

They did everything they could to make her weep properly. They slapped and punched her and kicked her feet out from under her. Twice, Sally watched them rub onions in Mary’s eyes.

Finally Sister Jane of the Rosary — she of the “green pill” razor strap — grabbed Mary by the scruff of her neck and announced that she was taking her to Mother Superior. Anybody who couldn’t cry, she said, was “completely nuts.”

That was the last time Sally saw Mary, although a short while later, one of the older girls announced that Mary had it made. She was with her parents, the other girl said. Mary, too, had gone home for good.

There was another child, a boy, who she heard had run away from the orphanage with his cousin. He was wearing a metal helmet, and somewhere along the way he crawled under a fence and was electrocuted. To teach Sally a lesson, the nun brought her, along with other naughty children, to his funeral.

The little boy lay in a small open coffin. He didn’t even look like a boy, Sally thought, just a blackened thing with holes all over him from being burned. A nun made Sally go up to the coffin. Then she told her to kiss the boy.

Sally was trapped. She leaned over the coffin, because she had to, but all she could see were the holes in the boy’s face.

As she bent down toward the boy, the nun whispered that if Sally ran away, the same thing would happen to her.

Sally didn’t let herself think about the strange disappearances or the gruesome death. During the day, she went about her business, and at night, lying there in the darkened dormitory, she tried to go right to sleep.

The nuns made the girls lie on their side and face the same direction. They had to put their hands together, as in prayer, and rest their head on them, then stay like that all through the night. If a girl’s hands slipped under the covers as she slept, a nun would wake her with a slap or send her to the attic. When Sally moved, a nun yanked her up by her hair and whipped her, before sending her back to bed — once more, hands in prayer on the pillow.

Robert Widman

I met Robert Widman at his house in Sarasota, Florida, on a balmy day in spring 2018. He had slightly wild gray hair and a deep tan, and his face crinkled up when he smiled, which he did a lot. He had retired from legal practice, and that morning, like every other, he had gone for a three-hour bicycle ride. Now he was dressed casually, in jeans and sandals. He was 70, but he stood and moved like someone who was much younger.

We sat down in a bright, airy room that opened out to a garden. Widman explained finer points of law, pausing to illustrate them with stories from his long career. Sometimes his wife, Cynthia, joined us.

I showed Widman some videos of his plaintiffs’ depositions. We watched a middle-aged woman with a sweet, soft face and a young girl’s voice talk about the day that she was standing in line at St. Joseph’s and the girl in front of her vomited. Enraged, the nun who was in charge that day told her to clean it up. When she couldn’t find anything to clean it up with, the nun replied, You know what I mean. You get down there and you lap it up. “It’s not fair,” the woman remembered thinking, but she knew if she spoke back, then the girls would suffer the consequences. So, she testified, “I did what I needed to do to survive and get out of there.” And as she spoke she started to cry. “I got down,” she said, “and I lapped up that vomit.”

Widman knew that kind of unfairness. Growing up in Norwalk, Ohio, in a Catholic family with its fair share of nuns and priests, he had been sent against his will to a Jesuit boarding school in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin. Give us a boy, the Jesuits told the parents of prospective students, and get back a man. Every night before bed, he said, boys who had earned a demerit were made to pull down their pants, bend over, and grab their ankles, so they could be beaten with a footwide paddle.

Decades later, he still remembered so many of the details from the St. Joseph’s fight, and still felt the injustice to which the institution’s former residents had been subjected. I showed him the video of Sally Dale talking about the boy she saw pushed out a window. “Ooh, she’s clear, isn’t she?” he said. He sounded proud of her. On the video, Sally recalls looking up to the fourth floor. “I saw the little body coming out,” she says. Widman let out a big sigh. “It’s depressing.”

Of all of the plaintiffs, Sally occupied a special place in his memory. When I asked about her, Widman’s eyes watered. Holding his fist to his heart, he said, “I just loved Sally Dale. I just loved her. She was really a special person.”

He believed Sally’s story about the boy being thrown through the window. But whenever Sally or another orphan told Widman about witnessing a death, his silent reaction was that there were no bodies, no witnesses, and no proof of any kind. He thought, “What the heck am I going to do with this?”

He wasn’t the only one.

Even countries that have conducted official government inquiries into the terrible stories of the orphanage system have shied away from stories about children who died there. Some, like Australia’s recent Royal Commission Into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, restricted themselves to an investigation of sexual assault. The narrowed focus distinguished between tortures in a way that made little sense to the people who had experienced them, and it made the stories about deaths seem more like hallucinatory one-offs than inevitable outcomes in a world of dehumanizing brutality.

Canada is perhaps the only country to have convened a special investigation into the thousands of Indigenous children who had gone to residential schools and never returned home. Kimberly Murray, an assistant deputy attorney general in Ontario who led the Missing Children Project, told me about former residents who recalled witnessing other children beaten to death or pushed from a window. For a number of these cases, Murray’s team found a record from the school that noted the death but did not include a cause or said that the child had died from accidentally falling out a window.

The stories I read of dead children at St. Joseph’s were just as brutal. In addition to the boy thrown from a window and the other one pushed into the lake, there was a story about another boy tied to a tree and left to freeze, and a newborn smothered in a crib. The stories haunted me, but despite the many resonances with tales from different orphanages, I found some of them just too much to believe. Like Sally’s wild tale about the boy who was electrocuted. She said there were holes in his face? And that he had been wearing a metal helmet? The details were too awful, too bizarre. Surely there was at least an element of delusion at work. And if it could creep into that story, what other recollections might it have colored? How could anyone ever nail down the facts?

At the start of the litigation, the stories of dead children were already between 30 and 60 years old. As with any cold case, the more time that passes between a crime and its investigation, the more likely it is that evidence will get corrupted or lost, that details will blur, that witnesses will die.

These cases presented additional challenges. They depended on accounts that took years to emerge into public view. In some cases, including Sally’s, they depended on memories that took decades to fully surface. That lag is common among victims of trauma, from children who were abused by family members to soldiers who suffered a devastating event on the battlefield. But at the time, psychology and neuroscience were only beginning to understand that delay; even now there remains tremendous cultural anxiety about the reliability of memories from the distant past, especially from childhood.

Finally, understanding these deaths required stepping fully into an eerie otherworld that few people today even know existed. Even when they were ubiquitous, orphanages were walled off from the rest of society. No one on the outside really knew what went on in them. Few really cared to.

Beds in the girls dormitory.

Two months after Widman filed Sally Dale’s case, in June 1996, he filed a case for Donald Shuttle, who said, “I lived in fear every day I was there.” In September he filed another three, including one for Marilyn Noble, who said, “She kept hitting me and hitting me and hitting, telling me to admit the truth. And I told her I was telling the truth, that I didn’t do it. And she kept hitting me until finally I said okay, I did it, to stop the hitting.”

Widman was also preparing more cases, like that of Debbie Hazen, who recalled, “Rather than just put me in the attic where there was windows, there was light up there, she put me in the trunk, because it was dark, and I was afraid of the dark.” William Richards: “They put a poker in a wood stove. … I watched the poker get red. Then I watched it get white.” Robert Cadorette: “He said, Bob, where are you, where are you, and then I came out of the bushes, and that’s when he grabbed me and took me down to the lake — and that’s when he tried to drown me.”

It had been obvious to Widman from the beginning, and only more so as the stories of his witnesses started to knit together, that he needed to bring all the plaintiffs together in front of the same jury in a consolidated trial. Each orphan’s account helped explain the context of every other account. In isolation, any one account could be more easily picked apart and cast into doubt. The plaintiffs would be vulnerable outcasts going up against one of the most powerful institutions in the world. Together they had a chance.

Joining the cases was critical on a practical level, too. The plaintiffs would need to call on each other as witnesses, but if each case was tried separately, they would have to return to the court and tell each story perhaps a dozen times, in front of strangers, an experience that many of his clients would find unbearable. The expert witnesses would have to be summoned again and again, and the court would need to assemble different juries for each case. The cost would be extraordinary.

The defense fought hard against letting all the plaintiffs join their cases together for a consolidated trial. It argued that it could prejudice a jury to hear stories from such a long timespan. And it challenged Widman’s witnesses, arguing that if they weren’t at St. Joseph’s at the exact same time as a given plaintiff, then their experience wasn’t relevant and would unfairly prejudice a jury. Sartore, the Sisters’ lawyer, later described the legal strategy to me as “traditional divide and conquer.”

The defense also fought Widman’s attempts to get the letters that Phil White had written on behalf of the survivors who took the initial $5,000 settlements. The letters would have been invaluable, practically a database of abuse and abusers. They could have offered proof that residents who didn’t even know each other faced the same tortures — and more importantly, that people in charge should have been aware of the problems. (Widman was also unable to get the letters directly from White, for reasons neither lawyer can now recall.)

The defense argued that when the bishop had asked former orphans to share their stories with him, he had done so out of a sense of compassion, and that he had given them the settlement money out of concern for their well-being. (If by paying the money, the diocese had also bought itself protection from further legal action, well, that was just incidental.) Sharing the letters with Widman, the argument continued, would undermine the bishop’s efforts to help the orphans, compromise the church’s freedom of religion, and violate the privacy of the people on whose behalf they had been written. Ultimately, the lawyers claimed, releasing the letters would harm the former residents’ relationship with the church.

But most of all, the church’s strategy was to emphasize the length of time that had passed since the alleged abuse took place. Long enough, the implication was, that no plaintiff’s memory, no matter how compelling, could ever be reliable. Long enough that no allegation, no matter how concrete, could ever be verified. There was simply no way to know any of it. The facts were lost in the mists of time.

At every opportunity the defense lawyers called the orphans’ claims, some of which dated back to the 1940s, “ancient,” “antediluvian” and “impossibly stale.” “Some claims were already stale before the onset of WWII!” went one memo from Sartore. “Indeed the hackneyed adjective ‘stale’ is hardly descriptive for these superannuated claims.”

It was a smart strategy. For the plaintiffs, it was also a cruel one. From their perspective, their long silence was not an accident; it had been forced on them, a direct result of the abuse they had suffered.

How many times had the children learned the lesson that no one was interested in their pain? If you cry, you cry alone. If you smile, the whole world smiles with you. How many times had they been punished for speaking up, leaving them to conclude that no one in power was interested in their problems? That their pain had no meaning inside or outside the orphanage walls? Again and again, they learned that their firsthand observations were not valid. The nun told Sally she had a vivid imagination. We are going to have to do something about you, child.

It took years — decades — for these survivors of St. Joseph’s to undo that indoctrination, to learn to trust their own perceptions, to reclaim their own experiences.

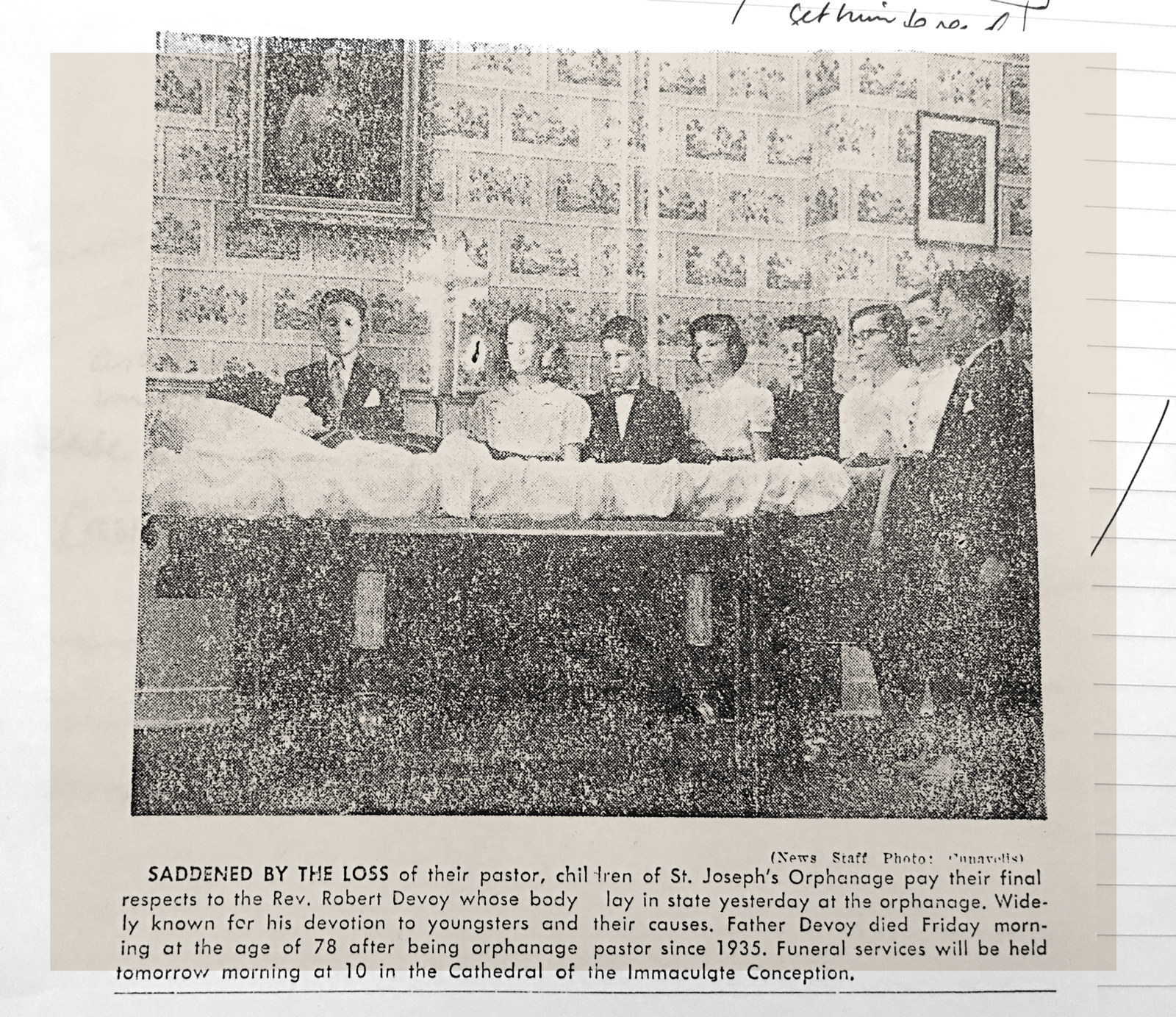

Still, the list of victims was growing, and so was the list of abusers. Sister Jane of the Rosary was remembered by a number of residents, as were Sister Claire, Sister Pauline, Sister Dominic, Sister James Mary, Sister Albert, and Sister Louis Hector. Of the men at the orphanage, Father Robert Devoy and Father Edward Foster, among others, were named.

Multiple laymen were also accused of molestation and other abuse. Fred Adams, who worked at the orphanage in the 1940s and sometimes wore a Boy Scout uniform, still haunted some of the boys of St. Joseph’s. Adams told one boy he would one day go to battle for America and needed to be able to tolerate torture if captured. Adams trussed the boy up and hung him from the ceiling. Then he tied a string to his penis. As he pulled on the string, the boy swung back and forth and smacked repeatedly into a hot bulb that was hanging behind him. Adams said, You can't say anything to jeopardize your fellow man… This is definitely going to happen to you. It’s just a learning.

Vivid though these images were, Widman was nervous about how they would fare in the litigation. In sex abuse cases across the United States, defense lawyers had started to challenge recovered memories. And privately, Widman was mystified by the various and inconsistent ways that plaintiffs’ childhood memories manifested themselves.

Then in Bennington, Vermont, he deposed two siblings, a brother and sister, former residents of St. Joseph’s who were serving as witnesses for the defense.

The sister, a slight woman in her forties, spoke positively about her time in the orphanage. At some point, Widman told me, he mentioned the name of the nun who had sewn with the girls, and who was said to have sexually assaulted more than one of them.

All of a sudden the woman became immobile, mute. It was like she was having a seizure.

Are you okay? Widman asked her.

She said, Oh my god.

He asked her again if she was okay, and she said, I remember.

Everyone froze.

She said, I remember what that nun did to me.

For one beat, no one moved. Then, Widman recalled, pandemonium broke out. The defense attorneys started yelling and screaming. What had Widman done? Had he given her money? Widman himself was frantic. What are you talking about? he asked her.

The woman said that she remembered what the nun had done to everyone, and that she had done it to her too.

Right there, in the middle of her deposition, one of the defense’s witnesses had recovered a memory of her own abuse at St. Joseph’s. She continued to serve as a witness — but for the plaintiffs.

It was happening in Canada too. In Montreal, less than 100 miles north of Burlington, former residents of Catholic orphanages were now coming forward to say that as long ago as the 1930s and as recently as 1965, they had been subjected to the most extraordinary abuse.

Just as with St. Joseph’s, the movement had started with a few voices and grown quickly from there. Just as with St. Joseph’s, the local press ran articles about the allegations and protestations from people defending the nuns. Just as with St. Joseph’s, one of the orders of nuns who ran the orphanages were members of the Sisters of Providence. Widman went to Montreal to learn more.

The survivors called themselves the Children of Duplessis, after Maurice Duplessis, Quebec’s conservative Catholic premier for much of the 1940s and 1950s. Duplessis observed that orphanages received only half the amount for each resident that hospitals and mental institutions received. So, working with the church and the medical establishment of the province, he engineered a plan to reclassify thousands of abandoned children as “deficients.”

As many as 5,000 children who had previously shown normal intelligence were diagnosed as “mentally handicapped.” Their education ceased. And they were pulled out of the orphanages where they had lived and moved into mental institutions. Often it was the defiant ones who were shipped off first. Some orphanages were simply rebranded as asylums, and untrained nuns were elevated to the status of psychiatric nurses — armed not just with their wooden paddles but with all the tools for treating mental illness in the 1950s, including restraints and intravenous sedatives.

The orphans’ lives after they left the institutions looked like the lives of the former residents of St. Joseph’s in Burlington. Many killed themselves or struggled with addiction and other damage. But many of those who survived were ready for a fight.

The Children of Duplessis were considerably more organized than Widman’s plaintiffs in Vermont. Their struggles had been chronicled in a book, Les Enfants de Duplessis, by the sociologist Pauline Gill. They had filed more than 100 criminal complaints against individual members of religious orders. The orphans’ attorney had filed a class-action petition asking for more than $1 billion in compensation. (The Canadian government eventually offered survivors compensation, ranging from $15,000 to $25,000.)

I asked one of the enfants, a woman named Alice Quinton, if she had seen any children die. She told me that one of her friends, an especially strong-willed girl named Evelyne Richard, died after being injected with the drug we now call Thorazine. Quinton especially remembered a little girl called Michelle, who was only about 4 years old, was said to have a brain tumor, and was often bruised and marked from beatings. Michelle cried all the time and was beaten all the time. A year after she arrived, one of the nuns discovered her body, stiff in the little straitjacket that she had been tied into.

Decades later, when Alice told her story to the police, they informed her that one of her tormentors had died at some point along the way. “They asked why I cried,” she told me, “and I said it was because I really wanted to take her to court.”

Hearing how the St. Joseph’s case echoed stories from other countries energized Widman. He also heard that a similar story was unfolding in Ireland. Adults who had grown up in residential schools run by Christian Brothers and different orders of nuns were starting to discuss how they had been assaulted, raped, and brutalized, and the police were investigating some of the cases. The Irish government was not doing much — the statute of limitations ruled out the pursuit of criminal charges — but it seemed clear that a storm was building.

A first-floor hallway of the now-closed St. Joseph’s Orphanage in Burlington, Vermont.

Around the time that Alice Quinton told me about the children who had died in the institution where she grew up, I was trying to track down all the stories about deaths from the St. Joseph’s litigation.

Scattered through the witness depositions, the stories were hard to piece together: How many deaths were claimed? Who saw them? When in the 40-odd-year period covered by the litigation had they occurred? Transcripts of witness depositions are usually very long documents, of which key excerpts are often all that’s filed in court. When I first came across the horrifying tales about a boy who drowned and a child who froze, I turned the page...only to find that the next 50 were missing. I frantically tried to cross-reference the accounts in other depositions and track down the witness, but usually I found only a whisper of the original story.

The orphanage was in operation for over 120 years. Thousands of people passed through its doors. It stood to reason that there would have been some fatalities along the way, even if only from natural causes. But the defense never offered an accounting of who had died and how, except in a few narrow instances when forced to.

Responding to Sally Dale’s story of the falling boy, Monsignor Paul Bresnehan — a handsome and articulate priest who was a leading light of liberal Catholic values in Vermont — told the Burlington Free Press it was “just simply unbelievable.” Which, for many people, it was.

A former resident named Sherry Huestis told a story that she had confided to her sister decades before: In the middle of the night, the seamstress, Eva, would sometimes pull Sherry out of bed to keep her company as she walked the hallways checking the doors. One night, Huestis testified, awful screams broke the silence, and Huestis followed Eva to a room where two nuns were hovering over another nun in the bed. The one in bed had her legs up and wide open. A little black baby was coming out.

The next day, Huestis went to her work in the nursery, and sure enough, the little baby was there, sweet and tiny. Huestis was off to one side when a nun came in, picked up a little satin pillow, and put it over the baby’s face.

The baby flailed its arms and legs at first. But when the nun lifted it up, its limbs dangled.

Huestis told the orphanage’s social worker what she had seen. Later, the nursery nun walked up to Huestis and slapped her good and hard across the face.

The idea that such heinous acts could have unfolded in one’s own town without anyone knowing was almost too much to take in. The church’s attorneys made the most of that skepticism.

I read the depositions of a number of former residents who, separately, described being made to kiss an old, dead man in his coffin at the orphanage. It was uncanny how many remembered the event. But the response of the defense was often to challenge the plaintiffs’ memories and even their very grasp of reality.

To one woman, David Borsykowsky, one of the attorneys for the Sisters, said:

“Now if I tell you that there is no record, no memory, no information that there was ever a funeral or ever a dead person at St. Joseph’s Orphanage, and that none of the sisters and none of the people responsible for children at St. Joseph’s have any memory or any record or recollection of any such event, does that help you to know that it didn’t happen at St. Joseph’s?”

That was more or less where the conversation ended. Borsykowsky didn’t actually say, and perhaps didn’t actually know, whether any deaths or funerals had transpired at St. Joseph’s. He just asked the plaintiff what she would say if he said that.

In another deposition, a man called Joseph Eskra, who spent time at St. Joseph’s in the 1950s and early 1960s, spoke about a hot summer day when an 11-year-old boy named Marvin Willette went missing at the lake. Another resident who was there at the same time described a large group of children standing on the shore of Lake Champlain and joining hands to form a human chain. Slowly the children walked into the water to search for a missing boy.

The children had to walk in a long way before the water reached their waists. Before they got to the sharp drop-off, the word came down the line that the boy had been found.

Eskra had last seen Willette out in the lake, where some bullies were trying to keep him from grabbing onto a floating log. Now someone carried him to the beach and laid him out on the sand in his striped bathing shorts, legs splayed. Soon firefighters were crouched around him trying to push air in as the sheriff, who had arrived in his patrol boat, stood nearby. But it was too late.

Eskra talked about another boy who failed to turn up at dinner one night. A group of about 20 set out with flashlights to look for him. They found him near the swing set, tied to a tree, frozen to death.

“That boy, for example, the boy who was — you say was frozen to death?” asked Borsykowsky. “That was something I’ve never heard about.”

Eskra took Borsykowsky at face value and tried to be helpful. “If you went back in the records, which I presume back then they kept records in Burlington, you would see if you looked through the deaths that there was something there, unless they hid it from the newspapers or from the records.”

“Okay. We’ve been looking for that and so far we haven’t been able to find it,” said Borsykowsky. “We view with skepticism much of what you’ve described.”

A tree at the edge of the property of the now-closed orphanage.

It was happening in Albany too, with survivors of an orphanage called St. Colman’s Home. The two cases played out in isolation, but I was amazed by the similarities: Though they were run by nuns from different orders, the orphanages were only 150 miles apart. The claims of former orphans — and the counter-claims of church supporters — were tearing each community apart. The stories made the front page of each local paper, but not a single person I interviewed from either case seemed to know about the other.

The Albany case had one crucial difference: Orphanage survivors had managed to get a police investigation.

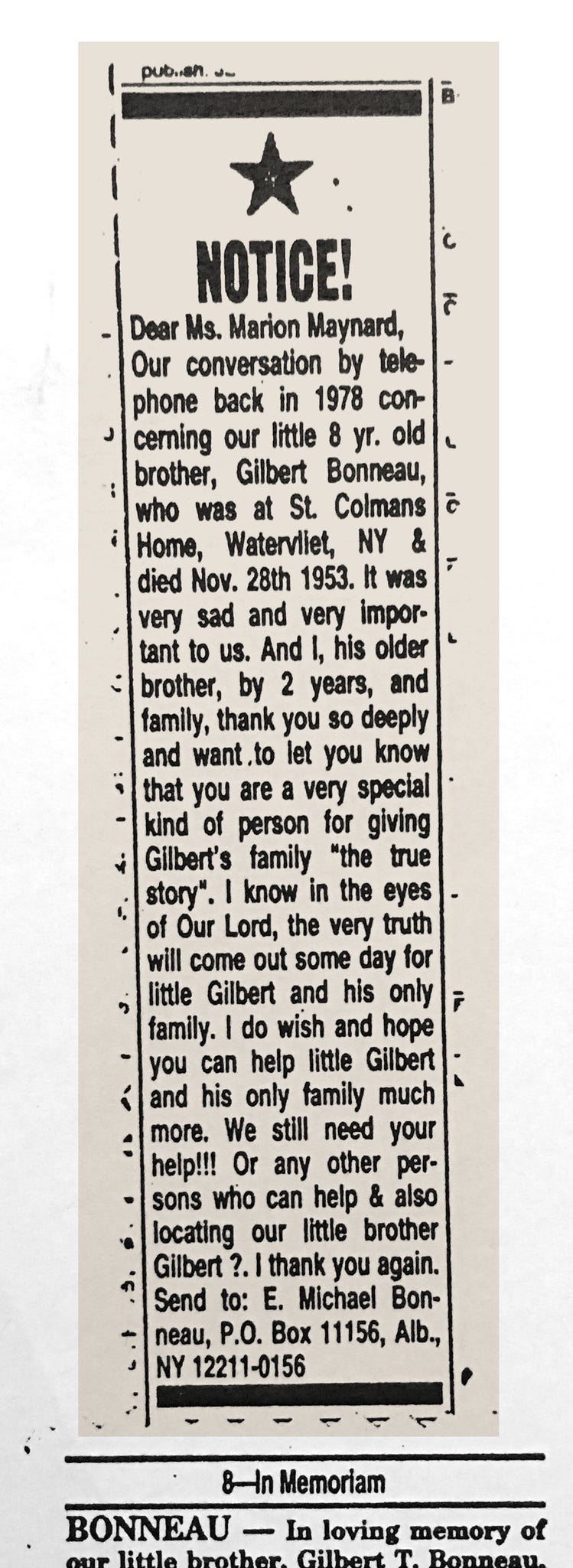

The Albany fight began with Bill Bonneau, who had seen his three younger brothers hauled off to St. Colman’s back in the 1950s. Only two made it out. The youngest, Gilbert, died when he was 8. Doctors said it was meningitis.

But in 1978, more than two decades later, Bill got a phone call from a stranger who said her name was Marian Maynard. Bill told me that Maynard had an urgent message about Gilbert: Before Gilbert died, he was beaten by a nun.

Maynard said the nun had savagely hit Gilbert in the head and he died the next day. For decades Maynard had kept the story to herself — but she happened to catch sight of the nun in Troy that day, then raced home and worked her way through all the Bonneaus in the phone book.

Bill was so stunned by the call that though he did his best to scribble down everything Maynard was saying, he didn’t think to ask her for a contact number. She ended the conversation promising to call him back. But days and then weeks and then years came and went, and the call never came.

One of Bill’s brothers placed an ad in the local newspaper begging Marion Maynard, or anyone who knew her, to get in touch with him. The ad ran for many years.

The ad that ran in local papers seeking more information.

It was 1995 when a local reporter named Dan Lynch noticed the ad and wondered if it came with a story.

The article that Lynch wrote for the Times Union in Albany asked, “Did Gilbert die after a beating by a nun? Was he a victim of a brutal institutional environment? Has the truth surrounding his death been covered up?” It ignited the same kind of angry, dismayed chaos that was engulfing Burlington. Dozens of former St. Colman’s kids came forward to talk about their time at the orphanage. One spoke of being thrown down concrete stairs, one was forced to kneel for hours in punishment, one was hung upside down in the laundry chute, and one was forced to eat his own vomit. Multiple witnesses said a nun stood on a boy’s leg until it broke. One heard it snap.

The police opened an investigation into Gilbert Bonneau’s death, but it quickly expanded to include the death of an older man with a disability, whom an aid worker said the nuns had deprived of oxygen; of Andrew Reyda, an orphan whom a witness said was savagely beaten by a nun shortly before he died in 1943 (police found two inconsistent sets of notes about the circumstances of his death); and of a boy named Mark Longale. He died in 1963.

Longale’s mother said a doctor at the hospital initially said that her son had injuries consistent with a bad blow or fall. But she was told later that the autopsy showed that her son’s appendix had burst.

In the 1990s, a witness would tell police that she had seen a nun brutally beat the boy days before he died.

A lawyer for St. Colman’s told me the institution declined to comment for this article.

The investigation into Gilbert’s death dragged on through the tenures of two different district attorneys.

Three forensic pathologists considered the case, one of whom examined Gilbert’s remains, which the family paid to have exhumed after more than 40 years. All three pathologists agreed there was no evidence that the boy died of meningitis. Finally, a witness who lived all the way in Florida came forward to say that he’d seen Gilbert in the infirmary bloody and screaming — and that he kept screaming until one of the nuns straddled him, put a pillow over his face, and smothered him. The man said he knew nothing about the investigation. He had simply posted a message to an internet forum that Bill Bonneau’s brother stumbled across.