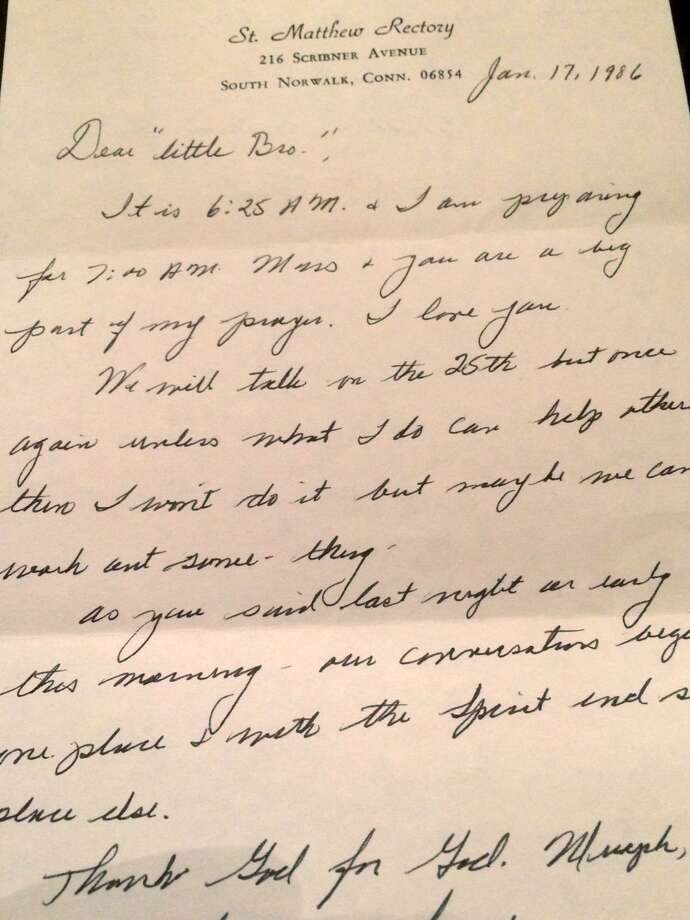

http://www.ctpost.com/local/article/Priest-s-sex-assault-in-New-Fairfield-11209556.php  NEW FAIRFIELD — When The Rev. Martin Federici looked out the window of the rectory of St. Edward Confessor Church that spring afternoon in 1984, he spied a 15-year-old boy getting the best of another in a fistfight. “Father Fed,” was drawn to athletic boys. Thirty-four years later the boy— who said he was sexually abused by Federici over a six-year period, starting that very day — accepted a settlement from the Roman Catholic Diocese of Bridgeport. The Church’s action this past week was the last to address the more than 60 people who claimed in lawsuits they were similarly victimized by priests in the 1970s and 80s. Related StoriesNow an adult, that boy says he is still suffering the aftershocks of those long ago sex assaults. Because he hasn’t told members of his family about the abuse, including his four teenage sons, he asked that Hearst Connecticut Media identify him only as “Patrick.” “People need to understand that this priest murdered the soul of this kid who grew up in New Fairfield,” Patrick said. “I didn’t know who that kid was anymore. That kid was murdered when he was 15, when the abuse began.” He said his troubled past has haunted him for years and even led to estrangement from his sons — but that one day soon he hopes to renew their relationship. “They may be old enough now to understand what made me what they thought was a monster as a father,” he said. “He went through a living hell and his story should remind us of the exploitation that is possible of our youth at the hands of a pedophile allowed to continue to prey upon the innocent,” said Patrick’s lawyer, Jason Tremont of Bridgeport. The parish shuffle In Patrick’s case the abuse occurred in church rectories in New Fairfield, Norwalk and at a religious retreat in Norwalk in the 1980s, all part of the Bridgeport Diocese. “The diocese’s lawyers wanted to put a money figure to each time I was abused,” he told Hearst. “They were all about the money. I told them I didn’t remember exactly how many times it happened, it was over and over again for six years.” In November 2014, Federici, who died in 2013, was named by the diocese as one of 29 “credibly accused clergy,” on a list it published on its website. But diocese records obtained by Hearst Connecticut Media through court action show the diocese was aware of abuse accusations against Federici going back to the 1960s. “The leaders of the diocese transferred Father Federici from parish to parish despite being aware of multiple complaints of sexual abuse of minors, all for the purpose of giving the priest a fresh start,” said Tremont, whose law firm sued the diocese on behalf of the more than 60 alleged victims, winning more than $35 million in total settlements. In 1968 Federici was pulled over while driving in Westport. Police noted there was a young boy in the car with him who appeared upset and whose clothing was in disarray. While the officer suspected Federici had been molesting the boy, he didn’t arrest the priest. But the incident was reported to diocese officials, according to their records. In 1971 Federici was accused of molesting a boy at St. Ambrose Church in Bridgeport. A psychologist told diocese officials Federici had "poor contact with reality ... the situation is not going to get better. He needs to be watched over and cared for like a child," the documents state. But in 1983, Federici was transferred by the diocese to St. Joseph's Church in Shelton, where he was accused of sexually assaulting a young boy in the confessional. Subsequently, Federici was transferred in 1984 to St. Edward the Confessor Church in New Fairfield. And in 1985, the diocese assigned him to St. Matthew's Parish in Norwalk. There, according to the documents, Federici ran up phone bills by calling sex hot lines. In 1989, Federici was assigned to Kolbe-Cathedral High School in Bridgeport. A counselor there reported that Federici had approached a young man during a weekend religious retreat, the documents state. In 1993, a Norwalk teenager said Federici forced him to watch as the priest masturbated at All-Saint's Catholic School in Norwalk. Patrick, now 50, and still trying to understand what happened to him, is employed as a respiratory therapist. Much of his story echoes that of abuse victims who have come forward around the country since the priest scandal became public. He grew up in a very religious family. Priests played a big role in the family and he was encouraged by his parents to seek the counsel of priests, who were looked on as being on a higher plane than ordinary people. Like many abuse victims, Patrick said he continued to hide his shame over what happened, leading him to become an alcoholic, he said. An early marriage ended in divorce and until recently he said he hasn’t been able to have a long-term relationship with a woman. Weekly counseling has helped he said, along with a supportive girlfriend. “I’m functioning,” he said. “Work helps. I’m working like 100 hours a week. When I’m not helping sick people I’m working my side job as a landscaper or doing something else. I’m still living in this prison that’s between my ears. The only cure is when I die, because then I don’t have to suffer anymore.” Priest and predator “In the early to mid-1980s when I was 15, I was getting off the school bus at the church — which was our bus stop— and I got involved in a fist fight with a classmate,” he recalled. “I didn’t remember what it was all about, but whatever it was, it was enough to get us swinging,” he said. “Father Federici saw us fighting from the rectory and after the fight he stopped me as I was walking by and that’s how it began.” At the urging of his parents, Patrick said he agreed to let Federici take him under his wing and counsel him at St. Edward the Confessor Church. “He was really impressed with my fighting ability he told me. After school he would call me to come into his room in the rectory to demonstrate how I fought,” he said. “He would ask me to remove my shirt and face the wall and talk about fighting. Eventually I caught on to what he was doing, he was masturbating behind my back while I talked about fighting,” Patrick said. “I probably should have told someone but who would have believed me?” Patrick admits he has trouble explaining why it just didn’t end there. In one sense he craved the attention the priest was giving him, but was horrified by what the priest went on to do to him. Over the next several years he said Federici sexually assaulted him. “He made me question my identity, telling me being with girls was bad but it was OK to be with him,” he said. “I knew I wasn’t gay, but here was this priest telling me that what he was doing to me was right,” he said. Patrick said the assaults continued when Federici was transferred to St. Matthews Church in Norwalk. It happened in Federici’s room in the rectory and in the basement of the church itself. “I can still tell you the colors of the walls in his room. I remember looking out the window in his room at a small pond outside and zoning out as it was going on,” he said. He said Federici also abused him during religious retreats the priest organized at Central Catholic High School in Norwalk. Edward Egan, who became Bridgeport’s bishop in 1988, took on the responsibility of continuing to hide the allegations of sexual abuse against priests in the diocese, according to diocese records, shuffling not only Federici but many other accused priests from parish to parish. Later, in a video-recorded deposition that was played during one of the court cases, Egan, who was elevated to cardinal of New York in 2001, tried to distance himself from the growing abuse scandal in the diocese claiming that priests were independent contractors. Mortification of the flesh When Patrick said he managed to get up the courage to call the diocese in 2014 to complain about the abuse he said he suffered at the hands of Federici and ask for help, he got a less than satisfactory response. “No one from the diocese returned any of my phone calls,” he said. “Instead, I was contacted by the state police who were concerned that I might be a danger. Can you imagine that? All I wanted was help and they instead reported me to the state police. That’s when I decided to call Jason (his lawyer).” Patrick said he is encouraged by actions the diocese is now taking. “The diocese continues to reaffirm its commitment to zero tolerance of child abuse, to remove from ministry anyone who has been credibly accused, and to bring healing and support to the victims and their families,” said Bridgeport Diocese spokesman Brian Wallace. As part of the settlement Patrick recently got to meet face to face with Bishop Frank Caggiano, who took over the diocese in September 2013. “He was sitting across the desk from me and I looked into his eyes as I told my story, and when I finished I could see he was really mortified,” Patrick said. “And then I showed him all the letters Federici had sent me and he was really upset.” Patrick spread out a number of letters Federici had sent him in the 1980s on the dining room table during a recent interview in his home, the same ones he said he showed the bishop. Each one is signed, “Father Fed.” In one dated Oct. 6, 1986, Federici writes, “I love you with a big hug! Praise to Jesus Christ.” “Meeting with the bishop was the step in that phase when the doors are beginning to open again,” Patrick said. “He set my mind at ease that things are being dealt with and I think the bishop understood that I never would have gone the court route if they had only called me back.”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.