|

Priest named on molestation list was Texas sniper’s scoutmaster, friend and confidant

By Jo Scott-Coe

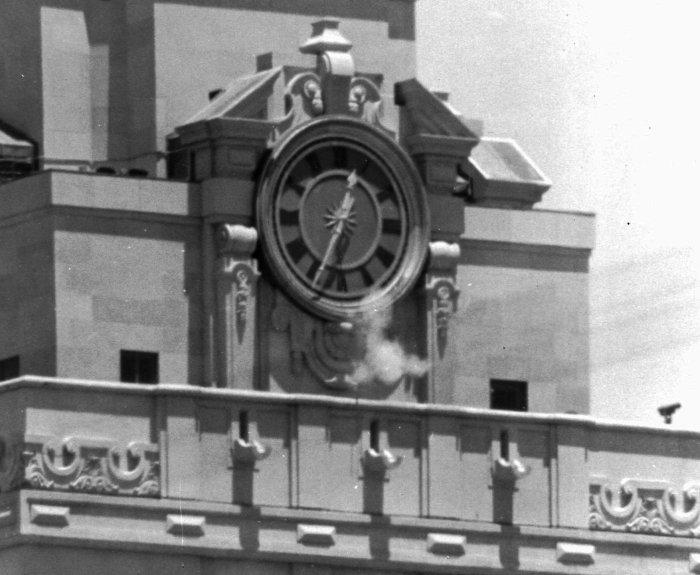

I could not let go of my nagging sense that the Rev. Joseph G. Leduc mattered more deeply than he had been credited On January 31, I saw the stunning, awful news. In Texas, the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston included the Rev. Joseph G. Leduc on its list of forty priests “credibly accused” of abusing children since 1950. As a writer who spent the past six years tracking Leduc’s life and its strange intersection with the story of the 1966 shooting at the University of Texas at Austin, I never thought I would see that revelation in my lifetime, though I had long suspected, and feared, the worst. In 2012, it had piqued my attention to discover that the FBI interviewed Leduc two weeks after Charles Whitman’s shooting rampage. Due to a combination of factors, however, the priest had virtually ghosted the historical narrative, meriting only a passing (and, as I later realized, often misspelled) mention in coverage of the massacre. As a Catholic by tradition and education, I could not let go of my nagging sense that Leduc mattered more deeply than he had been credited — as scoutmaster, friend, and confidant to a mass shooter. A lack of religious understanding may have caused others to overlook this part of Whitman’s story, and I knew that the priest’s presence was significant enough to merit more thoughtful interpretation. But how could I approach this elusive subject as an essayist? Leduc had been dead nearly three decades. When I started my search there was no public accusation against him, although I knew all too well the milieu in which I would be asking questions. More than a decade after The Boston Globe (think Spotlight) documented countless cases of abuse and a systemic pattern of cover-up by bishops and cardinals, my inquiries about a buried priest would be a minefield. Never mind that Leduc was connected to one of the most iconographic mass murders in American history. “MASS: A Sniper, a Father, and a Priest,” published in April by Pelekinesis, traced my wary portrait of Leduc as gleaned over six years of research, including primary documents and interviews, photographs and archives. I studied the secondary record intensely and foraged through newspaper reports, Catholic directories, military records, and genealogy resources. I visited homes and churches, libraries, schools, and seminaries in Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maryland, Florida, and Texas. I delved into the research of experts on Catholic history, culture, theology, and the priesthood to develop clearer insights and context for what I discovered. In all of the murky details, I found that Leduc was a troubling individual as well as an evocative symptom of a much larger pattern of secrets in the Church. I aimed to be as even-handed as possible, balancing fairness with skepticism. I worried about blowback from Catholics. I worried about over-idealizing. I worried that I hit my mark too well. I had to make room for simultaneous possibilities in order to preserve the broadest record. In his 1931 book Counter-Statement, Kenneth Burke explored the value of writers and critics who create narratives “at home in indecision, to humanize the state of doubt.” His point remains a valuable one. We often impose expectations on essays that make them easier to digest and to categorize. We recognize elegy, a song of mourning, or encomium, a song of praise. Some view the nonfiction essay, in particular, as a spittoon for linked facts more than reflection. What do we call a literary song for a shadow, especially when preserving that shadow may enable more knowledge to grow? We live and write at a time when audiences seem to demand certainty. But the essay forms I employed — lyric structures as well as narrative reportage — were ideal for a meditation on gaps in the story, on secrecy and shadows as well as my own doubts. Weaving Burke’s notion with my experience of Catholic tradition, I see essays as an opportunity for pilgrimage, a step-by-step encounter with the unknown alongside the evolving knowable. I found an inspiration and ally in this approach in my friend, Richard Sipe, a psychologist and former priest who authored groundbreaking and comprehensive research on the priesthood years before he died. Sipe was also a man who loved art and understood how literature can capture what is true before it becomes what readers call “history.” After MASS was released, I was nervous about the dark journey I had taken and also preserved. When asked by a writer friend whether I had any anxieties about potentially negative reactions from bishops or other church authorities, I told her I was doing all right for now. That’s when another writer chimed in with a blithe shrug. “It’s just a book,” she said. “It literally doesn’t matter at all. They have many more important things to care about.” It sounds almost funny now, the certainty of that dismissal, but it points to the larger problem of pre-emptive erasure. I know that Leduc’s story does matter, and that people other than myself have indeed cared, and will. But where are they? Have I created a pathway through MASS where we might encounter each other, to understand what is necessary for healing? Any vindication in seeing Leduc’s name on a list of abusive priests is balanced by what his inclusion continues to hide. The diocese has not revealed how many victims or counts of abuse are alleged, or when complaints were made. We do not know whether any survivors are still alive, or whether some are bound by nondisclosure agreements. I cannot help but wonder whether Whitman himself complained about Leduc before he took his guns to the top of the tower.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.