|

Parishioners Gather to Support Bronx Bishop Accused of Sexual Abuse

By Emily Palmer

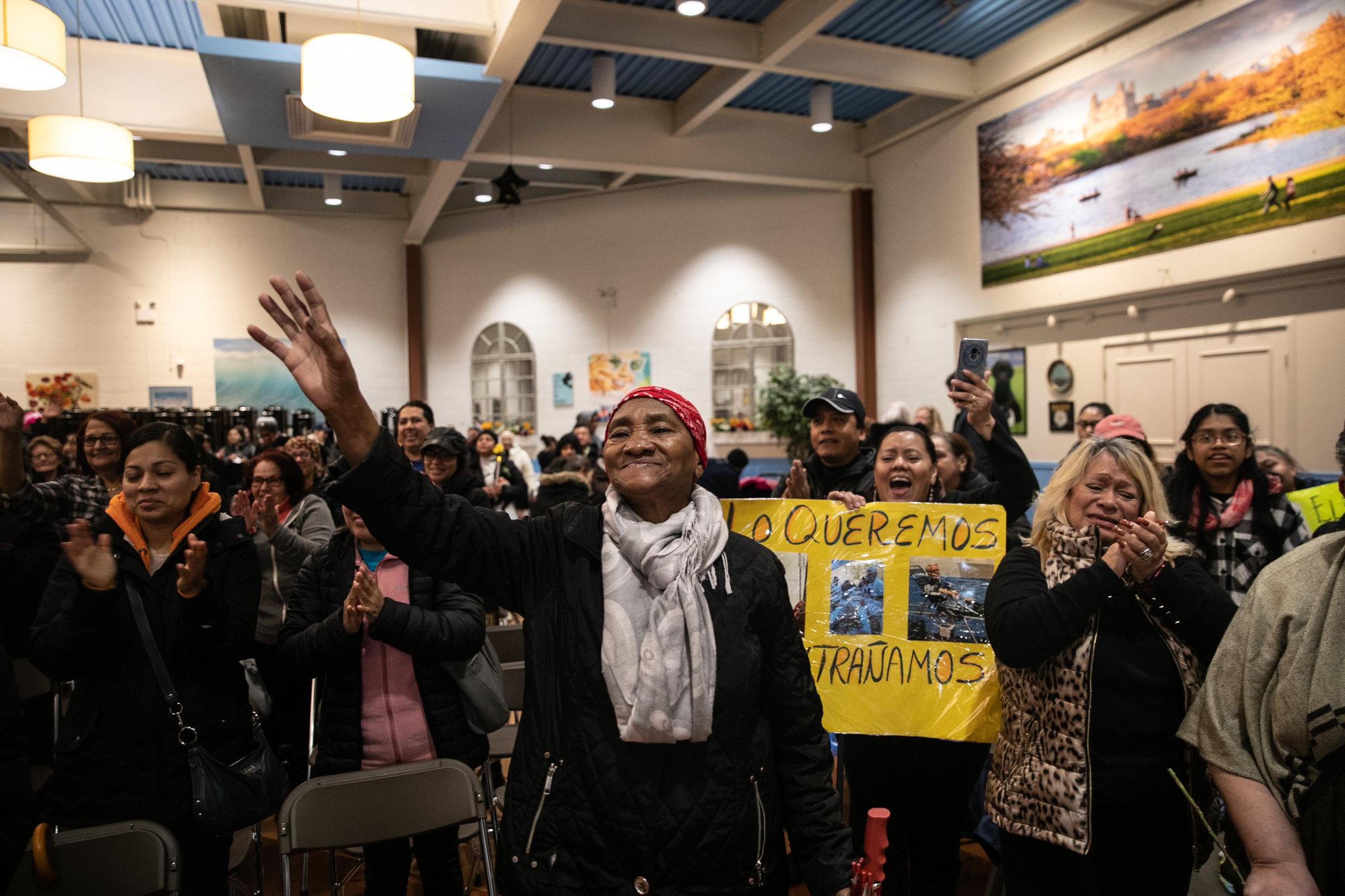

On Friday evening, inside Our Lady of Refuge church in the Bronx, a man tapped on his phone and then raised it high, so each of the approximately 250 people in attendance could see the screen. Rushing toward the man with the phone, the crowd shouted out the name of John Jenik, an auxiliary bishop who was barred from the church on Oct. 29, following a recent allegation that he had an inappropriate relationship with a teenage boy in the 1980s. Bishop Jenik has denied the accusation, but after an investigation by the Archdiocese of New York, Cardinal Timothy M. Dolan called the allegation “credible and substantiated.” An independent commission affiliated with the archdiocese is considering the claim for a cash settlement, and the case has moved to the Vatican for a review process that could take years. Since his banishment, Bishop Jenik, 74, has been living at a rehabilitation center without access to his parish. Many in the church do not believe the allegation, and some gathered on a rainy Friday evening in support. But they were not expecting to see and greet the bishop — even through a FaceTime call. “Muchísimas gracias a todos,” Bishop Jenik said, thanking them for their support. In recent years, as additional allegations of sexual abuse by priests surface — more than a dozen states are investigating abuse claims after a cover-up in Pennsylvania involving at least 300 priests — it is not uncommon to see a parish support the accused. But the size of the crowd on Friday was noteworthy. As the church bells rang at 5 p.m., parishioners gathered in the church hall to wrap handmade signs — written in English, Spanish and Vietnamese — and a framed depiction of Jesus in clear tape before marching into a deluge of rain through the very neighborhood the bishop helped restore. A canopy of umbrellas snaked along the sidewalks. A nun prayed in Spanish through a megaphone. Some supporters carried electric candles, others rainproofed signs. One man, standing across the street with his own sign, yelled, “Support Jenik’s victim.” The marchers remained silent as they passed, continuing onward about a mile. Michael J. Meenan, 52, accused Bishop Jenik in January, and said in an interview last month that he became close to him when he was 13. According to Mr. Meenan, the bishop often invited him to sleep at his home and served alcohol. Once, while sharing a bed, the bishop touched his body through the sheets, Mr. Meenan said. Mr. Meenan’s attorney, Mitchell Garabedian, who has worked on more than 2,000 clerical sexual abuse cases, said on Sunday he is exploring allegations by two other people that question the bishop’s “moral fitness” but do not allege sexual abuse. The archdiocese did not immediately return a request for comment regarding Mr. Meenan’s case. Bishop Jenik is the first seated bishop to be accused of sexual misconduct against a minor since a new wave of allegations flooded the Roman Catholic Church this summer, spurred by the resignation of Cardinal Theodore E. McCarrick after allegations of decades of abuse against children and adults. In September the New York State attorney general issued subpoenas to all eight of the state’s dioceses and announced a statewide civil investigation into allegations of sexual abuse and cover-ups. A month later the Department of Justice instructed every Roman Catholic diocese in the country to maintain documentation of their handling of child sex abuse — signaling a deepening investigation into an issue that has largely remained within the Catholic Church’s purview. “The Catholic Church is guilty of criminal acts over the course of decades upon decades, worldwide,” Mr. Garabedian said. “It’s not reasonable to then think that the Catholic Church can self-police in a fair manner. Take away their robes and their religion and they’re just criminals.” Letters of support for the bishop, written in English and Spanish, have expressed discontent with the church-run system and indicated the preference of a court trial. (Mr. Meenan’s allegation does not fall within the state’s statute of limitations.) John Garcia, the executive director of Fordham Bedford Community Services, a nonprofit organization that Bishop Jenik chairs, said the bishop had fought for the community. “He’s been our voice, our fighter. He stood up for us when no one else did,” he said, adding, “There’s nothing short of a smoking gun that will make us believe he could have done this.” On Friday night, Mr. Garcia, one of the few people who has been allowed to visit the bishop, addressed the crowd in Spanish: “I see the bishop almost every day, and he loves you so, so, so much.” Then, on a whim, he dialed the bishop’s number. When Bishop Jenik answered, Mr. Garcia held the phone so parishioners could see him over FaceTime. “Oh my God, he’s there,” shouted Nancy Nguyen, who had traveled from Staten Island to attend. An older woman cried from the corner, and Katty Amato wrapped her arms around her. Ms. Amato, 46, recalled that after she was evicted, Bishop Jenik helped her secure a two-bedroom apartment through the Fordham Bedford Housing Corporation, an affordable housing program that he helped start when he joined the parish in 1978. “I keep asking every night, ‘Why is this happening to him?’” Ms. Amato said. “But I think God is testing the community: us, and him too.” She added: “We’re not giving up on him.”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.