|

One bishop could lead the way to another bishop being the first charged for sex abuse

By Judy L. Thomas

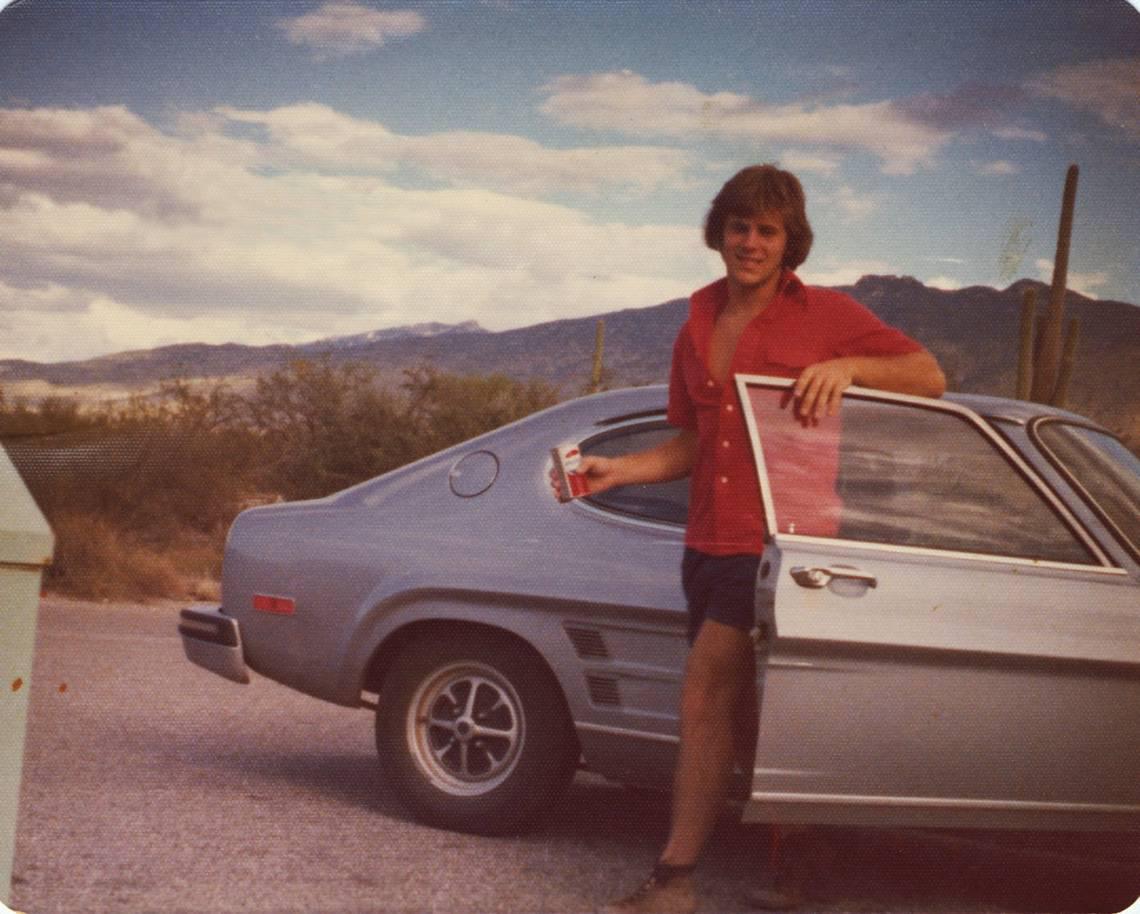

[with video] The call last year from Pope Francis’ representative in Washington took the Rev. Steven Biegler by surprise. A priest in South Dakota, Biegler learned he was the choice to become the ninth bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Cheyenne, Wyo., leading the state’s 55,000 Catholics. Though sad to leave his parishioners in Rapid City, Biegler was eager to begin ministering to a diocese that encompasses the entire state of Wyoming and covers nearly 100,000 square miles. Biegler said he was excited to be continuing his journey “of saying yes to the Lord.” But as it turned out, one of his first major decisions upon arriving in Cheyenne involved saying no. No to a man who for nearly a quarter century had run the diocese he was now going to lead. A man who spent his first two decades as a beloved priest in Kansas City. And a man who — in large part because of Biegler’s persistence — could become the first Roman Catholic bishop in the country to be prosecuted for sexual abuse of a minor. Bishop Joseph Hart, 87, stands accused of multiple acts of sexual abuse now deemed credible by both the Missouri and Wyoming dioceses that he served. And though the allegations involve incidents from decades ago, Wyoming stands out from most states when it comes to criminal prosecutions. It has no statute of limitations on criminal cases. Biegler learned about the complaints against Hart from outgoing Bishop Paul Etienne on his initial visit to Cheyenne. Then Biegler heard that Hart wanted to attend his bishop ordination ceremony. “So I went to visit him shortly after I arrived in Cheyenne, prior to the ordination,” Biegler said in an interview with The Star. “And I said that I wouldn’t allow him to concelebrate because of the allegations and because Bishop Etienne had already put a protocol in place regarding limitations on his public ministry.” Hart didn’t take it well, Biegler said. “He said, ‘That will be the most embarrassing day of my life.’” Biegler didn’t waste any time confronting the issue in his new diocese. He began looking into why a 2002 criminal investigation into allegations against Hart was dropped and obtained the Vatican’s permission to hire an investigator to re-examine the case. And when the investigator — who had handled more than 200 other sex abuse cases across the country — reported back, Biegler turned the information over to the district attorney in Cheyenne. Then he flew to the East Coast for an emotional meeting with the former Wyoming man whose story prosecutors had deemed not credible 16 years before. In July, Biegler issued a news release that stunned Catholics and non-Catholics alike. He announced that the diocese had reopened its investigation into Bishop Hart, proclaimed that the previous investigation was flawed and said two allegations had now been deemed “credible and substantiated.” Not only that, Biegler said, the diocese was cooperating with a new police investigation, and he hoped the Vatican also would find the allegations to be credible and take disciplinary action. Hart has categorically denied all allegations, both in Kansas City and Cheyenne. He recently responded to a knock on the door of his Cheyenne home. “I’ve been told not to talk,” Hart said, “but you could call my lawyer.” He was on oxygen but told The Star that “I feel fine. Doing great.” Then he closed the door, which bore a plaque that said, “Peace to all who enter here.” Hart’s attorney, Tom Jubin, said he was not commenting further about the case. He issued a news release following the diocese’s July announcement, calling it “a bizarre press release that is both shocking and appalling.” Jubin’s news release included a statement from Hart, who noted that the 2002 investigation had concluded that the accusations against him had no merit. “I am confident these processes will, in the end, come to a similar conclusion,” Hart said. He said he would fully cooperate with the new investigation and “will continue to pray that those who have suffered abuse, no matter at whose hands, receive justice and healing.” In August, the Cheyenne diocese issued another statement. A third Wyoming man had come forward and reported that he had been sexually abused by Hart in 1980. That allegation, the diocese said, also was found to be credible and substantiated. Hart’s accusers — some of whom left the church long ago — say Biegler, 59, is giving them a renewed hope for justice. The bishop, they say, is “the real deal,” an honorable man of God who is trying to do the right thing. “After he became bishop, he called and asked if I would meet with him,” said the sister of the former Cheyenne man whose allegations prompted the investigation in 2002. “And the first thing out of his mouth was, ‘I believe that your brother was a victim of molestation by Joseph Hart.’ “And I just broke down. It was like this big weight had been lifted off my shoulders. I started sobbing, and he got teary-eyed himself. He’s a good man.” A Kansas City familyThe sight nearly made Susie Hunter McClernon sick to her stomach. She was at a St. Patrick’s Day party in 1992, and there was Bishop Hart joining in the celebration. Hart had been a dear friend of the Hunter family for years; their mother worked for him when he was a priest in the Kansas City-St. Joseph Diocese, and his gold-framed picture hung on the family’s living room wall. “I was very, very close to Bishop Hart,” McClernon told The Star in a recent interview. “He was like a father to me. I remember writing a story about who was the most influential person in your life, and it was him. I loved the man, I really did.” When her youngest brother, Kevin, had trouble adjusting during his freshman year at Rockhurst High School, their mother turned to Hart for help. And in the summer of 1971, Stella Hunter saw it as a blessing when Hart offered to take Kevin on a road trip with him through the American Southwest.

Kevin’s siblings said their brother, 14 at the time, was never the same after he returned. He became brooding and insular, transferred to another high school and got into drugs before he graduated. By his mid-20s, his life had spiraled downward into a world of drug abuse. At the same time, Hart was rising through the Catholic hierarchy, serving several Kansas City parishes after his ordination in 1956. In 1976, he was promoted to auxiliary bishop of the Diocese of Cheyenne. Two years later, he became bishop of the sprawling diocese. But Hart never lost sight of his Kansas City roots, coming back often to visit his mother and brother, who also was a priest. In the spring of 1984, Mike Hunter arranged for Kevin to meet with Bishop Hart during one of his Kansas City visits in hopes that Hart could help his struggling brother. But when Mike Hunter picked Kevin up afterward, his brother was a mess. And his words have haunted the family ever since: “You don’t understand. Bishop Hart is the reason I am the way I am.” Kevin Hunter said he was a victim of sexual abuse by Hart, molested on the summer road trip and forced to sleep with him. Kevin’s siblings were devastated but never breathed a word to their parents. Kevin died of AIDS in 1989 at age 31. As much as McClernon loved Hart, she never doubted Kevin. “I went to him a few days before he died,” she said. “I didn’t want to believe, and I knew Kevin had taken a lot of drugs and thought maybe this was a trick of his brain. And I said, ‘Is there any way that you may have misunderstood what happened between you and Bishop Hart?’ And he looked me straight in the eyes, and his eyes just filled with tears, and he said, ‘No, Susie, it happened.’ And I knew he was telling the truth.” Something their mother did led the siblings to believe that Kevin eventually told her about Hart as well. Before she died, Stella Hunter wrote a confidential letter that was to be delivered to him upon her death. They don’t know if their father ever gave it to Hart, who said the eulogy at Stella Hunter’s funeral. McClernon and another sister also wrote to Hart. Hart wrote McClernon back. “He said that his life wasn’t the same since all of this had happened,” she said. “It was more about him. He didn’t deny it. He didn’t say he did it. Basically, he said that he was praying for our family.” McClernon couldn’t let it go. “It was very hard,” she said. “I remember trying to decide what to do, and then we were invited to a St. Patrick’s Day party with all my parents’ old friends.” That’s where she saw Bishop Hart. “And he had a boy that was probably 12, 13 years old with him that he had brought from Cheyenne,” Susie said. “We were all very close to his mother, too. She was a sweet lady. And she said to my sister Patty, ‘I’m so proud of him, because every time he travels, he brings a young boy with him. It’s just so wonderful how much he loves the boys.’ “That was the point where I realized that I couldn’t keep quiet.” The family met twice with representatives of the Kansas City-St. Joseph Diocese. They were told at the second meeting that Hart had been sent away for evaluation, giving the impression that he had a drinking problem. Mike Hunter asked if Hart would remain Bishop of Cheyenne, and they said yes. “We didn’t understand,” McClernon said. “And I said, ‘Will he be kept away from boys?’ And they said, ‘Oh, yeah. But you know, he’s out of our jurisdiction.’” The diocese then offered counseling for any of the siblings who wanted it. Two of the sisters accepted. But what the diocese didn’t offer the Hunters was the rest of the story. They later found that they weren’t the first to bring forth allegations against Hart. Another Kansas City man also had contacted the diocese, saying Hart had sexually abused him as a sixth- or seventh-grader in the mid-70s. That man told The Star years later that the diocese put him in touch with a psychologist and paid for his counseling for about a year. And in July 1993, the diocese paid $12,100 toward a new extended-cab pickup for the man. It wasn’t until 2002, in the aftermath of the national church sex abuse scandal exposed by The Boston Globe, that the diocese issued a statement acknowledging that it had received two allegations and had helped pay for counseling and provided “some limited financial assistance” to one man. The diocese said it had deemed both allegations not credible but had informed the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and the Papal Nuncio of the complaints. The vicar general told The Star, however, that there was no indication in the diocese’s records that law enforcement authorities had ever been notified. The statement said the diocese had recommended that Hart undergo a full psychiatric evaluation and that he had done so at an institution in Tucson, Ariz., in February 1993. The month-long evaluation found that Hart “does not appear to be a threat to himself or others on any level,” the diocese said, and he returned to his ministry in Cheyenne. Allegation surfaces in WyomingIn Cheyenne, the Kansas City story quickly caught the eye of a woman whose brother as a young teen had worked for Hart at the bishop’s residence. She called her brother, who was living in New York City. “I was in shock,” the man told The Star in a series of recent interviews. “It’s like you feel horror that it happened to more people, but there’s also a relief that I wasn’t alone somehow.” His sister begged him to come forward with the story that he’d shared with her just the year before, on the eve of his wedding. He soon contacted Cheyenne authorities to report that he, too, was a victim of sexual abuse by Hart. He told them that he was coerced into exposing himself in front of Hart in 1977, while Hart was auxiliary bishop in Wyoming. Some of the abuse, he said, took place during the sacrament of confession. He also said he had memories of Hart taking him on out-of-town trips, including to a Royals game in Kansas City. “The reason I spoke up was because the kid in Kansas City, his brother said he was fine until he started going on these trips with the bishop,” the man told The Star. “And I said, ‘Wait a second. I went on those trips with the bishop, and whatever he’s saying is true. And I can’t let this kid be maligned when he’s dead, because I know his family and him spoke the truth.’” One Kansas City trip is “crystal clear” to him, he said, but his memory is fuzzy on other incidents. “I don’t know what month it was, but I can remember that his breath smelled like cigarettes,” he said. “And that there was a pack of cigarettes and a glass with bourbon next to the bed on a Saturday morning.” After contacting police in 2002, the man said, a detective interviewed him. “He basically said to me, ‘This is a pillar of the community you’re attacking. Is this really something you want to do?’ He was not at all interested in getting to the facts. Didn’t even care about any of the details.” He had already been through two traumatic incidents in his life since leaving Cheyenne after high school graduation. One nearly killed him. The other was 9-11. He lived 10 blocks from ground zero. The man asked not to be named because he does not want the abuse to define who he is. He saw a therapist after the life-threatening incident. During his sessions, he told her he’d been sexually abused by Hart. But when he mentioned that to the Cheyenne police detective, thinking it would lend credibility to his story, the investigator immediately downplayed the significance, he said. “He said to me, ‘So these recovered memories that your therapist got out of you’ ... and I was like, ‘No, no. They weren’t recovered memories. I just had never told anybody about them before.’” By then, the man started feeling like he was the one on trial. “So at that point I just said to my wife, ‘I can’t be the person for this. I’m just wiped out from the rest of my life.’” The Laramie County District Attorney had cited a conflict of interest in the case and referred it to a special prosecutor to investigate. Kevin Meenan, the Natrona County District Attorney in Casper, Wyo., issued a news release in July 2002 saying Hart had been cleared of any wrongdoing and that “it is clear that the allegations are without merit.” Keeping tabs from Kansas City, Mike Hunter questioned the thoroughness of the Wyoming investigation. No one in Cheyenne ever contacted any of his family members, he said. “When you’re investigating, you think that you’d talk to someone who has raised similar concerns,” he said. “What kind of investigation is that?” Those weren’t the only concerns raised about the case. Some people in Cheyenne said there were too many close connections between the Catholic Church and those conducting the investigation. The lead investigator was a Catholic convert, and a former diocesan official told The Star that Meenan was a parishioner of Hart’s when Hart was auxiliary bishop and serving at St. Patrick’s Church in Casper. The Wyoming accuser’s sister said the cozy relationships with the church rendered her brother’s case dead on arrival. She said she never doubted he was telling the truth. She vividly recalls the times Bishop Hart would call their mom, asking her to send her brother over to help with something, such as unloading his luggage after returning from a trip. And the hours she’d spent on the back steps of the bishop’s house, waiting for her brother to come out so they could walk home together. And the look of despair on his face when the door was flung open. “And then they said, ‘Well, the victim didn’t cooperate so we didn’t have anything to go on,’” she said of investigators. “But he did give enough information to where they could have looked into it. The thing is that they just didn’t believe him.” Investigations gain momentumWhen he became Bishop of Cheyenne in June 2017, Biegler said, his predecessor had already laid some of the groundwork. Bishop Etienne had contacted the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith at the Vatican in June 2010 and asked them to open an investigation into the claims against Hart. That September, Etienne went to Rome to attend training for new bishops. While there, Etienne visited with Vatican officials about Hart’s case. And in 2011, they began an investigation. At the time, Biegler said, there were nine allegations against Hart. But Etienne never heard back from the Vatican. So as Biegler prepared to become the new bishop, he contacted the Papal Nuncio in Washington, D.C., to ask about the status of the investigation. “And the results were that they could not come to a moral certainty regarding the allegations,” Biegler said. “However, there were three allegations that raised serious questions.” One was from Cheyenne. The other two were from Kansas City. When Biegler attended bishops’ training in Rome in September 2017, he met with the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith to talk about Hart’s case. “We had information about each of those nine allegations because we had been in contact with the Diocese of Kansas City-St. Joseph, and we had information that came from Rome’s investigation,” Biegler said. The Vatican officials told Biegler they still could not come to a “moral determination” on Hart’s case but authorized him to investigate. The diocese hired an experienced investigator who interviewed the accuser and his family members. He spent hours talking to the former Cheyenne man in person, recorded an interview and got a signed affidavit. He also filed open records requests with Cheyenne police to obtain information from their 2002 investigation. “Not only did they have details, but they had several elements of corroborating evidence,” Biegler said. “Two of the family members offered around seven corroborating facts, and Bishop Hart himself corroborated a few of the facts in terms of what took place.” Armed with the investigator’s findings, Biegler met with the Diocesan Review Board and members of his staff. They agreed that there was now enough information to report a credible allegation to law enforcement. Biegler paid another visit to Hart, this time to tell the retired bishop that the diocese was going to contact authorities. “Obviously, he was disturbed,” Biegler said. “But the reaction wasn’t as strong as I anticipated it would be.” The next day, Biegler turned over the investigation results to the district attorney in Cheyenne. This time, Hart’s accuser said when he talked to police he was encouraged by how he was treated. “The guy that spoke to me was really great,” he said. “And you realize that they’ve been through some kind of sex crime training by their gentleness. You could just tell by the way he asked the questions that he had experience with speaking to people who were traumatized.” Once police had conducted their interview, there was one more thing Biegler needed to do. Book a flight to New York. ‘We both cried’Hart’s accuser and the resolute bishop met face-to-face in May. “He sat with me for hours,” the man said. “We both cried. It was an unbelievably wrenching experience. “I thought, here’s somebody who seems like he’s a hero, but he’s actually just doing what he’s supposed to do. But then I have to say that he went beyond that. He went beyond somebody who’s not protecting the guilty. He did and said everything with the utmost sincerity.” Biegler was deeply moved by the meeting. “My gosh, this man has endured so much,” he said. “I was impressed by the resilience of the human spirit, and then the goodness of not just being stuck in hurt for himself, but the goodness of a man who’s trying to deal with the healing that he needs, but raising a family, concern for other victims. “That’s pretty moving to experience that kind of goodness in a man.” Did he believe the man after meeting with him? “I believed him before meeting with him,” Biegler said. “I suppose that strengthened in the personal meeting with him, but I was already there. I already had a good sense that he was credible.” Biegler said he was particularly struck by one question the man asked. “Toward the end of our conversation, he said to me, ‘If others come forward, will you listen to them?’” Biegler said. “So this is a man that’s not just focused on himself. And I think it’s the question that victims have. Should I even speak, and will I be heard? I think the church and society have both failed to offer an atmosphere in which victims feel that they will be heard.” The bishop has stayed in touch, the man said, and kept him apprised of progress on the case. “He’s just been somebody that when I lose faith in the hierarchy, here is our lonely bishop out in Wyoming still waving the banner,” he said. Hope for justiceThe Hunters say that, even after all this time, the pain hasn’t gone away. And it intensified in July when they saw the stories from Cheyenne saying the investigation had been reopened. “I was very upset because the reports said that our family was not deemed credible,” McClernon said. “So I called Bishop (James) Johnston and I broke down and told him pretty much the whole story.” Johnston, who became bishop in Kansas City in 2015, asked to meet with her. When they did, she said, he came with a victim’s advocate, not a lawyer. “I said, ‘Do you believe me?’ And he said yes. He said, ‘I’ve heard the story, but I have not heard your family’s side of the story.’ He said he would pray for me and he thought my story was very moving.” Soon after, she called him back and said it wasn’t right that news reports were still saying that the Kansas City-St. Joseph Diocese didn’t think their allegations were credible. “That’s not fair to my family,” she told Johnston. “The diocese knew there was another accusation when we went to them. That in itself should have given our family some credibility. And he said, ‘You’re right, Susie, and I will make it right.’ And they did.” In August, a diocesan spokesman called The Star to request that future stories about the case note the diocese and Bishop Johnston now deem those allegations credible. “I think what they haven’t grasped and they are just beginning to grasp is the collateral damage,” McClernon said. “And that’s why we need to tell this story. They do need to see that it’s not just the one victim. There are many victims.” McClernon was living in Arkansas when the original story came out in 2002. The stress, she said, caused her to have a nervous breakdown. “We’ve lost five people in the family now,” she said, referring to her parents, Kevin, their oldest sister Mary Lou, and Mike, who died in 2015. “I truly believe in my heart that for all five of them, this contributed to their early deaths.” The church’s investigation is now complete, Biegler said, and the Vatican is reviewing the case. The criminal investigation in Cheyenne will likely be wrapped up early next year, said police spokesman Kevin Malatesta. Biegler said his hope is for a final resolution to the case, both for the diocese and especially for the victims. “Part of their healing is that they have been heard and that there is a response that shows that they’ve been heard and that there are actions that are being taken,” he said. “I want to state clearly that we have credible allegations and I do strongly believe that they require disciplinary action.” Hart’s accusers have mixed feelings about what they think should happen to him. “I don’t have a desire to see Bishop Hart go to jail,” McClernon said. “I pity him, but best-case scenario for me would be that he would say, ‘I did this and I’m sorry.’ But that’s probably never going to happen.” McClernon is the only one of her siblings who remains a Catholic. “I’m brokenhearted by what men in the church have done,” she said. “I love the Catholic church. I will be Catholic until I die. And I have tried to use it to change what is happening in the church. “But unless the truth comes out, we can’t begin to heal.” Her brother, Darrel Hunter, said his hope is for a greater understanding of the issue. “So when a boy comes forward, he’s listened to and the assumption isn’t that this kid decided out of the blue to say something bad about father so-and-so,” he said. “And when a woman has an issue, she doesn’t wait to say something because she’s afraid.” Kathy Donegan said Hart destroyed her best friend and soul mate. “And it wasn’t just that I lost Kevin,” she said of her brother. “I didn’t have my mom. She was doing absolutely everything for Bishop Hart. She was his secretary. She did all his Christmas shopping, birthday shopping, and he never paid her back. He always used her car when he came in town. Mom, bless her heart, I just didn’t have the right kind of teenage years. And I blame Hart for all of that.” The former Cheyenne man said he would take no pleasure in seeing Hart go to prison. “As much as I’m a fan of punishment for his actions, sending an 87-year-old man to a state pen is not my idea of justice,” he said. “But having the State of Wyoming say, ‘We believe the victims,’ is a good start.” Thanks to Biegler, the man’s sister said, there’s finally hope for justice. And healing. “He has changed my life,” she said, fighting back tears. “For 20 years, I have had lots of friends who have died who are Catholic. But I have not been able to go into St. Mary’s Church without feeling physically ill. Now, I walk up and I feel so good. It’s like, ‘Yep, they believe him. They believe my brother.’ “Hart could die tomorrow, and I wouldn’t even care. Because now I know that they know.”

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.