When Boy Told of Sexual Abuse, His Parents Asked the Priest Who Raped Him to Counsel Him

By Sam Ruland

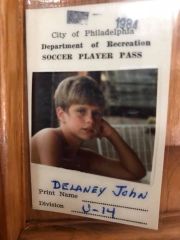

Soon after, he was acting out — starting fights in school, drinking, coming home late — hoping that someone would notice, that someone would care. "I couldn't understand why my parents didn't help me," Delaney said. Instead, he said, his behavior was dismissed, shrugged off by parents and teachers labeling him a “bad kid.” "And they were kind of happy that I was spending time with a priest, ya know — like he'd be the one to straighten me out." 'Nobody will believe you' He hit his breaking point when he was about 13 years old. An argument after detention led to him telling his parents what Brzyski was doing to him, and had been doing to him for years. His parents didn’t believe him though. “You don’t lie about a priest like that,” Delaney father's said as he slapped his son across the face. “They didn’t know what to do with me.” Delaney said his parents did reach out to the priest following his confession to them. However, it wasn’t to protect him like he had hoped, and said he needed. They asked his abuser to counsel him — “their son was troubled,” giving Brzyski even more access to him. So Delaney went to counseling. With the man who had been raping him. He threatened the priest, saying he would tell more people, but was confronted with an unbearable truth: Nobody believed him. “The priest said to me,” Delaney recalled, “‘Go ahead and tell. Nobody will believe you. Your mother and father already know about this and that’s why they sent you to me.’” He felt trapped. His abuser manipulated him and had a way of making Delaney feel alone and isolated. “He was a bully,” Delaney said. “That’s how these guys work. He made me feel like dirt. He said my father didn’t care about me, that he was only my step-father, so I wasn’t really his son.” And that only drove the wedge between him and his parents deeper. His father has passed away since then, never fully getting the chance to understand the abuse.

But, Delaney said, if his father was around one thing is certain: "it be hard, but he would have been with me every step of the way — every court hearing, every interview." "I think this would have rocked his faith," Delaney said referencing his father who worked as a detective in Philadelphia. "Here's a guy who was supposed to protect people all day as his job, and he couldn't protect his son. I think that would have destroyed him." The relationship with his mother, or lack thereof, is more complicated. She still criticizes Delaney for "going public" with his abuse, he said. Delaney said he last spoke with her four or five years ago. He lives in Tennessee now and doesn't even know her direct contact information at this point. The grand jury report shows that Delaney’s parents weren’t the only ones to respond with anger, or to ignore the allegations of abuse, when their children told them. In a case outlined in Pennsylvania’s grand jury report, one woman was met with even more abuse when she told her father about the priest who abused her — her father beat her with his belt. The woman was allegedly sexually assaulted by Father Francis Fromholzer while she was a student at Allentown Central Catholic High School. According to the grand jury report, Fromholzer touched her and her friend “inappropriately” while on a trip to the Poconos. She told the high school principal, but not her parents. As noted in the report, her parents were both alcoholics, and father physically abusive. The principal did not engage in the conversation for long. Instead, he told her she was expelled from school and needed to bring her father in to his office for a meeting. That’s when the principal asked her this question: “Now, I want you to tell that story that you said — the made-up story that you said about the priest to your father — with your father here.” So before she even told her father about the sexual abuse she had endured, she was labeled a liar, just as Delaney had been. 'This is something that is black and white' There isn’t a “right” way for a parent to react when they are told their child has been abused, according to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network’s official website. But according to Delaney, there certainly is a wrong way, a way that he says makes things worse. “When a kid tells you they’ve been abused,” Delaney said, “that’s it. You put everything else aside. You don’t hold them acting up against them. You support them and you believe them.” The website offers parents some advice, telling them to repeat the following messages through both their words and actions if their child discloses abuse to them: I love you. What happened is not your fault. I will do everything I can to keep you safe.

“For it being a such a complex issue, child sexual abuse,” Delaney said, “this is something that is black and white.” Why don’t some parents seem to understand that though? Or why don’t they share a similar perception? Delaney said for his parents, maybe it was their generation that was to blame, growing up as such devoted Catholics. He recalled how his grandmother was a real “church-goer,” attending Mass every day and twice on Sundays. “It’s ingrained in you through that Catholicism,” Delaney said. “Priests really were treated like they were above everything else. And I can understand why then it was hard to accept that — but that doesn’t excuse it.” And while experts have stressed that there is no acceptable excuse, they have tried to provide some explanations as to why some parents responded this way, expressing anger or disbelief. “The culture of the church plays in to their response,” said Nick Ingala, communications director of the Voice of the Faithful, a lay organization of Catholics that formed because of the sexual abuse crisis. The abuse is about power, Ingala said — the child is powerless and the abuser has all the power. More: Will more states follow Pa.'s lead and investigate priest abuse? Here's what they say More: After the grand jury report's release: How to talk to kids about sexual abuse “It’s power over the weak,” Ingala said. “So if a parent doesn’t believe their child, it discourages them from coming forward again. The child suppresses the memory.” Delaney said he could relate to that. Telling his parents, and being rejected in a sense, deterred Delaney from reporting the abuse to anyone else until years later when he was an adult. “I was an out-of-control kid,” Delaney said. “But I was no dummy. You beat me once for something, I’m not going to come back again and get beat again. I wasn’t that stupid — so I didn’t tell anyone else.” It’s a way to test the waters, Haven Evans said. Evans works as the director of training at the Pennsylvania Family Support Alliance. Her experiences with children have taught her many things, but in regard to this particular topic, she said it reminds her just how perceptive children are. “They [children] may not initially elaborate on the full scope of the abuse,” Evans said. "And it’s not them changing the story, it’s them asking ‘Is mommy going to be OK if I tell her this.’” And Delaney said based on his parents’ reactions, it was clear that it wasn’t OK. "Nothing that I told them was OK with them," Delaney said. "They were in denial." Evans said that denial is a common emotion for parents to go through when they learn that their child has been abused — "a parent loses their ability to be a good parent." "They don't want to believe that this could happen," Evans said. "They don't want to believe that someone they trusted could hurt their child like this." So, Evans said, they ignore the situation. She described it as a form of neglect on the parents' part. Instead of dealing with the allegations, it's easier for them to pretend it didn't happen, or that they weren't told. "Because once they know," Evans said. "It falls on them, too. They become responsible, and for some people that's too much to handle." Delaney spent a part of his childhood locked behind bars. After he came forward to his parents, and his temper worsened, they sent him away. “They had me charged incorrigible, and I became a ward of the state,” Delaney said. He bounced around to different boys' homes and institutions for three years. Delaney, now 47 and a parent himself, said he’ll never understand how his mother or father didn’t do more — how they didn’t get to the root of his violent and erratic behavior and give him the help he said he so desperately wanted and needed. “I needed to hear that somebody believed me, especially my mom and dad,” Delaney said as he continued to list off the things he wished would have happened when he came forward as a child. “I needed someone to tell me they loved me. And I needed somebody to just listen and get me some help and make it stop.” “Nobody was there, NOBODY,” his voice escalating, as he emphasized the word. “The people who were supposed to protect me and care about me, weren’t there to do it. And that changes you.” Now, working as an advocate for survivors like him, Delaney said he hopes his willingness to share his story will inspire others to do the same. And he’ll be there to listen.

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.