In the Rear of St. Joseph's Roman Catholic Church, the Old School Friends of the Man in the Casket Were Growing Agitated. the Funeral Service for Jim Cunningham Was about to Begin.

By Maria Panaritis

It was a terrible loss: A 45-year-old father, prison counselor, and hostage negotiator dead by suicide. Handkerchiefs were out in the other pews. But near the back, fury decades in the making was boiling over. "No. I can't do it," Kevin Emery told the others. "We can't stay here for this." Like Cunningham, each had been a student in the same Northeast Philadelphia parish school, St. Cecilia's, in the 1980s when the Rev. James Brzyski turned their community into a stalking ground. Brzyski (BRISH-kee) had sexually assaulted possibly more than 100 boys during stints at St. Cecilia's and a prior parish, St. John the Evangelist in Lower Makefield, a grand jury later asserted, but like so many abusers had eluded prosecution. As far as any of Cunningham's boyhood friends had known, the scrawny bookworm with a million-dollar smile had been among the lucky altar boys to avoid the predator's reach. He had earned a master's degree, built a career, even won a seat on his local board of supervisors. But in truth, his world had spiraled over a simmering torment: long-ago abuse at the hands of Brzyski. His anguish peaked one February night in Doylestown, surrounded by the same Bucks County SWAT team he had helped with suicide standoffs. His mom had called the police to save her distraught son. Inside, Cunningham had posted a note on Facebook: "This is the face of being raped as a child." Emery had a screenshot of that message on the smartphone in his pocket. He thought about it as three priests hovered near Cunningham's casket. This was the second funeral in a year for the St. Cecilia's crew. Classmate Jimmy Spoerl, raped by Brzyski as an altar boy, died in March 2016 after his trauma- and addiction-ravaged body gave up on him. Another victim, John Delaney, sobbed in a pew at the Mass for Cunningham. Others, like Gerad Argeros, stayed away from both funerals, afraid of the demons they might stir. These men and those who loved them were among a lost generation at St. Cecilia's. Casualties of long-hushed childhood horrors that seemed to have no end. Yet since being labeled a pedophile and walking away from the church decades ago, and despite little dispute about the damage he inflicted on children while wearing a collar, Brzyski roamed the country a free man. His whereabouts had long been a mystery though one soon to be solved.

Until he began telling friends last year, Cunningham wasn't known to be one of the priest's victims. Even then, he had kept specifics mostly to himself. Experts say as many as one in four girls and one in six boys endure some form of sexual abuse by age 18. Many hide, ignore, or repress the memories for years until they confront their secret trauma or are destroyed by it. As Emery and others left the Warrington church in protest, Cunningham's mother, a secretary at another Catholic parish, remained in the front row. A few pews back was Mike Bruzas, another St. Cecilia's alum and Cunningham's best friend. Brzyski had never targeted him, but he, too, felt damaged. "Why did I survive and they didn't? Was it just luck?" Bruzas would later wonder. "It just doesn't seem fair that they kind of stole a part of everyone's childhood." Ripe to be exploited St. Cecilia's was more than a sanctuary full of pews. Its buildings the rectory, school, gym, and the church itself blanketed an entire block in Fox Chase, a neighborhood so full of Catholic families in the 1980s that thousands of worshipers made the parish among the region's largest. The Rhawn Street compound, as one altar boy called it, was the center of prayer and social identity. Kids spent almost as much time there as at home. Their neighborhood was packed with police and firefighters, factory workers and secretaries, and stay-at-home moms. They raised their children with sometimes unyielding discipline, some with an unflinching devotion to the church. Being an altar boy conferred status.

Cunningham's family moved from Summerdale into a small twin on Lawndale Avenue in the late 1970s. His dad was a shipping company worker and a eucharistic minister at Sunday Mass. Jamie, as his family called him, was the oldest of four children. Bruzas lived next door; his dad was an auto parts factory worker. Mike and Jamie became fast friends. With a third boy around the corner, the son of an officer, the trio became the Three Amigos of the neighborhood, playing all day long, in woods behind the house, stealing factory cardboard to make forts, walking on the railroad tracks. "You've seen the movie Stand by Me?" Bruzas asked. "That always reminded me of our childhood." Jamie was a good student and dapper little guy who never left for school without tucking in his shirt or combing his hair neatly to the side. "He looked like a politician," a fellow alumnus of the class of 1985, Louie DiNofa, recalled fondly. He was a clever but kind soul, said his sister, Kristen Ott: "That 'old man' that could talk to anybody." Every morning, she and Jamie left for St. Cecilia's on foot, joining the other boys along the way. Their dad would tag along as far as the SEPTA bus stop, where he began his downtown commute. On weekends, the kids would make the same trek again for Mass. Obedience. Trust. Devotion to the faith. These were the values in Fox Chase. It was an ethos ripe to be exploited by a predatory priest. Suffering in silence

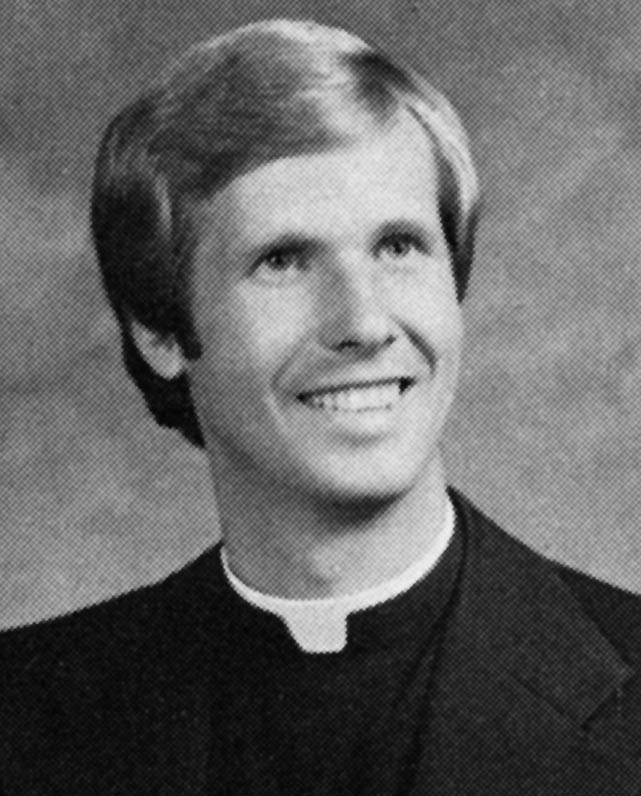

The young priest lorded over the altar boys as they queued up in line for practice one afternoon. Brzyski was militant about them holding their palms together with fingers pointed to the sky; interlacing fingers was akin to pointing to the devil. Anyone who didn't get it right would suffer the consequences: the 6-foot-5, 220-pound priest wrapping his hands around their knotted fingers until their knuckles felt like they were cracking. On this day in the early 1980s, he exploded in anger. An altar boy in line was giggling. Brzyski grabbed him and tossed him headfirst through the confessional's velvet curtains. "What is this guy doing?" Emery thought at the time, petrified. Brzyski had been a priest for four years when he became associate pastor of St. Cecilia's in 1981. Then 30 and the son of a cop, he seemed relatable to the boys. Only years later would parishioners learn the charismatic cleric had sexually assaulted children during his first assignment in Lower Makefield. Brzyski favored a certain type of boy "shy, docile, bright, and intelligent and ... all physically attractive" and as young as 10, a grand jury would later assert.

He targeted children with fragile home lives or exceptionally devout parents, better to keep his sordid acts under wraps. This was a common strategy among pedophiles: They fished in troubled waters. Delaney fit the profile. Altar boy of the year, soccer player, and son of a police officer. But a shy kid, a little kid, whose stepfather drank and who had a bad relationship with his mother. "I came from a broken home," he said. Delaney was just 12 and weighed 80 pounds when Brzyski raped him, he later told prosecutors. Over three years, Brzyski abused him in the grade school, the rectory, and the church sacristy. Once, he was alone in the priest's bedroom when he found a metal lockbox in an armoire. Inside were photos of teen boys, many nude, some from St. Cecilia's. But nobody would talk about what they knew. Argeros was another target. The altar boy lived a block from the church with his sister, his dad, who was a Teamsters truck driver, and his mom, a part-time secretary. St. Cecilia's felt like home to the youngster. At age 11, the priest raped him, pressing him facedown on the rectory floor. Adding to his torture, his job as a newspaper carrier required him to return to the priests' residence each afternoon to drop off the evening Bulletin.

Sitting in religion class later, he and the other children were told that priests were the infallible embodiment of Jesus Christ. Argeros would come to think his terror was God's plan. Jimmy Spoerl had four brothers, a sister, and strict Catholic parents the kind who were thrilled that a priest visited their home and showed interest in their son. They did not know Brzyski was pulling Spoerl from his classes in fifth grade to sexually abuse him. Spoerl, too, buried the horror. Once, he threatened Brzyski that he was going to tell his parents about the abuse. Brzyski scoffed, he said, and cowed him with a lie: He said Spoerl's mom and dad not only knew about their contact they sanctioned it. "He was afraid to go to school," his mother, Catherine Spoerl, said in an interview this year, "and he was afraid to come home."

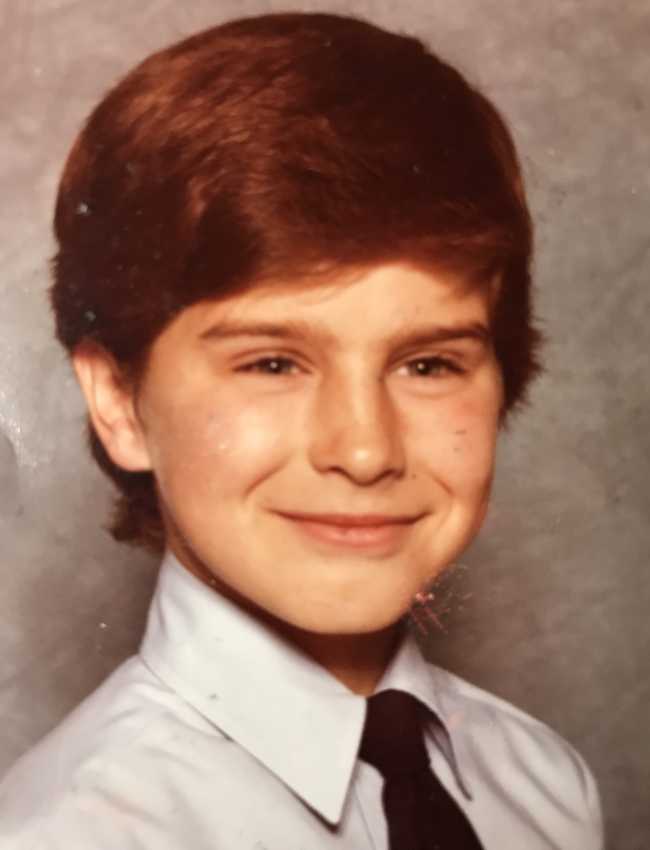

Jimmy Spoerl was in 5th grade at St. Cecilias when Rev. Brzyski began to sexually abuse him in the early 1980s, a grand jury asserted. Spoerl died in March 2016. Among the parish adults, there had been signs, even suspicions. Some quietly gave the associate pastor a nickname: Frisky Brzyski. Years later, one victim would tell the grand jury about the time a priest had walked into the St. Cecilia's sacristy as Brzyski was fondling his genitals only to walk out. But nothing happened. In 1984, Brzyski suddenly disappeared from Fox Chase. A whistle-blower priest had given archdiocesan officials evidence that Brzyski had abused boys at the Lower Makefield parish. Brzyski admitted "several acts of sexual misconduct," including with a 7th grader, church officials' records would later show. They sent Brzyski to a treatment center for priests in Maryland, where a top clinician declared him to be a pedophile. The archdiocese, however, did not tell parishioners the truth. "They said he had a mental breakdown," Catherine Spoerl recalled. "It said so in the parish bulletin." Then-Cardinal Krol privately described the priest as a "wolf in sheep's clothing." But he took no steps to notify law enforcement, even after Brzyski walked out of treatment and abandoned ministry in 1985. Not long after, one of Krol's top aides ordered in writing that no effort be made to identify his victims at St. Cecilia's. Scandal explodes, victims implode The furor over clergy sex abuse may have been ignited in 2002 by revelations in Boston, but the patterns of conduct and long-term impact on victims followed the same path worldwide. Children who are sexually assaulted often wrestle silently for decades, unable to understand or process their abuse. Some blame themselves, some question their sexuality, many plunge into destructive addictive behavior. Clergy abuse stings with still more psychological poison: victims attacked by a man of God. The boys from St. Cecilia's were no different. Delaney and Spoerl battled drugs, alcohol, or depression and began acting out as they entered high school. Argeros, too, lost his way. A high school guidance counselor chided him for not performing up to his high IQ. A few years later, he dropped out of George Washington University. Once in the early 1990s, Argeros, then back from college, was in a Roxborough diner when he spotted Brzyski in a booth. They exchanged glances but no words. Still, the encounter shook him. In the ensuing years, he began to lose his grip, even grapple with suicidal thoughts. A critical moment came in 1998, he said, after he had moved to New York and was giving stand-up comedy a try. One night, the manager at a comedy club touched his thigh; Argeros dashed to a friend's apartment and panted three words. They had to do with Brzyski. "He got me!" Argeros called out. "He got me!"

|

.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.