|

| The Death of Father Larson

By Rod Dreher

American Conservative

September 8, 2014

http://www.theamericanconservative.com/dreher/the-death-of-father-larson/

This news jolted me when I learned it just now:

Robert Larson, the Catholic priest convicted of sexually abusing altar boys while serving in the Wichita diocese, has died.

Diocesan officials on Thursday said Larson died Aug. 27 at the age of 84. He was buried in his home state of Michigan.

“We pray for all victims of sexual abuse and for their families,” the Most Rev. Carl Kemme, bishop of the Wichita diocese, said in a statement following Larson’s death. “We continue to learn from them and we recommit ourselves to vigilance in protecting children and young people from the tragedy of sexual abuse.”

Bob Larson was not just any child-molesting priest. As the Wichita Eagle reported back in 2000, Larson destroyed a number of lives. Here, from a National Review Online piece I wrote in 2002, is the story of several of them:

No statistics exist documenting the number of clergy-abuse victims who have killed themselves, but stories like that of Horace and Janet Patterson of Conway Springs, Kansas give us a feel for the worst kind of pain priest sexual abuse can contribute to. In the fall of 1999, their son Eric, 29, shot himself in the head with a Colt .45, ending years of torment that seemed to begin when he was first molested at age 12.

He was an altar boy. His attacker was the Rev. Robert Larson, his parish priest.

Eric didn’t tell his devoutly Catholic family what was being done to him, his father told NRO. They sensed something was wrong with him, but assumed his depression was just part of growing up. He drifted far from the faith as an older teenager, but returned to the Church with great enthusiasm as a junior in college. Daily mass, holy hours, teaching religion class to kids, visiting the elderly, writing to prisoners — these were all part of Eric’s new commitment to faith.

In 1993, he spent three months in a Legionaries of Christ seminary before they sent him away, telling him he didn’t have a vocation to that order. His depression returned and intensified. He began rubbing his skin raw in an obsessive attempt to get clean. He told his family that he loved God, but couldn’t satisfy Him. There were other signs of serious mental disorder.

“Eric would fast severely,” Horace says. “I guess he was atoning, but he would just stop eating. He would get so thin, and we just didn’t know what to do.”

The family compared his gaunt look to that of a concentration-camp victim. What they didn’t realize at the time was that eating disorders can be a sign of sexual-abuse trauma. Eric’s psychiatrist asked him if he had been sexually abused, and he denied it. She told Eric’s parents she could find no cause for his depression, but said he was clearly suffering from post-traumatic-stress disorder, with psychotic tendencies.

The second time Eric was hospitalized for depression, in February of 1999, his sister Becky visited him in the hospital. She told him, “Mom and I just hate your idea of God, some vengeful, vindictive God. We look upon God as a loving, merciful God.”

He told her he didn’t feel that way about God until he was 12, when “Father Larson practically raped me.” Becky immediately told the nurse, who informed Eric’s psychiatrist. When the nurse went to check on him, she found Eric bashing his head against the tile floor. He was placed in full-body restraints, and put on suicide watch.

“The next day, we went to the diocese, in Wichita,” Horace recalls. “We were babes in the woods.”

When Janet told a priest official there what Eric had confessed, the cleric acted surprised to hear it. The priest told her that Fr. Larson had been taken out of ministry in 1988 after similar allegations — six years after he left in Eric’s parish — and sent away for treatment. She assumed that that was the first Church authorities knew of Larson’s tendencies.

Eric left the hospital and moved back in with his family. When his health improved that summer, he rented a house nearby with a roommate. Eric went into another tailspin that fall, one that ended with his suicide.

“It’s a day you can’t take back, when a policeman and a minister come to your door to give you the news,” Horace says. “I sat outside for two hours, crying and waiting for the family to come home to tell them.”

In the suicide note, which his father still has not been able to read, Eric said he was tired of not being able to measure up to God’s expectations. Says Janet today, “No one should blow their brains out because they think they can’t please God enough. I keep talking to victims of priest sex abuse who say that they know intellectually it wasn’t their fault, but that they just can’t feel clean.”

After the funeral, the Pattersons began telling friends that Larson had molested Eric. Word spread quickly, and they discovered that there had been rumors about Larson for years. In January 2000, the Pattersons learned that the diocese had been informed in 1981 — a year and a half before Larson came to the Pattersons’ parish — that Larson had molested a Wichita altar boy in 1972.

The Church knew Larson was a pederast, but sent him into parish ministry anyway. And Eric Patterson was only one of his victims.

“After Eric’s death, we were horrified to discover that [Larson] had begun molesting boys in the late ’60s in Wichita, then molested many Vietnamese refugee boys when he was in charge of the Vietnamese relocation program for the diocese in the ’70s, then was sent for treatment for alcoholism,” Janet alleges. “There was a pattern of [diocesan] lying that went on.”

It turns out that five — five! — boys who had been molested by Larson eventually committed suicide. By the time investigations stopped, 17 victims of Larson had been identified.

Hearing of Larson’s death gets to me, because I well remember the telephone conversation I had with Horace Patterson on the day I interviewed him for that NRO article. He described to me sitting on his front porch after having received the news by phone of Eric’s suicide. He watched his wife Janet driving up the lane towards the house, knowing what he was going to have to tell her when she arrived.

Something inside me broke when I heard that story. I was at the time a relatively new father; my son was not yet three. I imagined myself in Horace’s chair on that day. I imagined myself in the places of all the parents of Father Larson’s dead. What would I say to the bishop(s) who allowed Father Larson to remain in ministry, knowing what he was? What would I say to the diocesan officials who repeatedly lied to mothers and fathers about this monster the diocese allowed to come into their midst and prey on their children?

After this essay appeared online, I heard from a Vietnamese-American man who said he was one of the boat people refugees that Father Larson had responsibility for. He too had been molested by the priest, but like so many of the other boys, he did not have the language to tell others what was happening to him. And he was a child in a foreign land. He was scared. They all were.

And the Diocese of Wichita let this happen to them.

Read the Boston Globe‘s account of the five young men, victims of Larson, who killed themselves. Bobby Thompson, one of the men, was abused by Larson starting at age 8:

His mother wrote a letter to Wichita Bishop Eugene Gerber, asking about rumors of Larson’s abuse, wondering whether it could help explain her son’s steep psychological slide. The church’s reply, received two years after the diocese had removed Larson for sexual molestation and sent him to a Maryland treatment center, was curt, unresponsive, and silent about Larson’s abusive conduct, she said.

By the fall of 1996, 21-year-old Bobby Thompson was working for the local library district, shelving books. On the afternoon of Oct. 4, he walked into his mother’s closed garage, started his car’s engine, and sat down to die.

”It has just become too much pain and trouble for me to continue on,” he wrote in a note. ”Thank you for always trying to help me out. The fault for this is not yours. You did everything you could. I don’t want any regret for anyone as this should leave with me. I have seen over and over again that my life will never be how I want it to be. So I have to take the easy way out. Goodbye and love always. Your child, Bobby J. Thompson.”

I can say now that it was that interview with Horace Patterson that planted the seed that ended with me losing my Catholic faith four years later. Horace, though estranged at the time from the church (I don’t know what his status is today), didn’t try to talk me out of being Catholic. He didn’t have to. Every time I talked to a parent of a victim after that, or read a story in the media, I thought, That could have been me; that could have been my child. The bishop would have thrown us to the wolves.

David Clohessy of SNAP issued a statement after Larson’s death. Excerpt:

Fr. Larson was accused of assaulting 17 kids. So logically, given the devastation he caused, I should have been relieved at the news of his passing. And initially, I was.

I called the mother of one of Fr. Larson’s victims, a kind, generous and smart woman named Janet Patterson. She immediately said to me what I’ve often said when predators die: “At least now, we know he’ll never hurt another child.”

But guess how Janet heard about Fr. Larson’s death?

From the bishop? Nope.

From a diocesan official? Nope.

From a parish priest? Nope.

From a concerned Catholic? Nope.

From the same journalist who called me.

Is that too much to expect – that a bishop (in this case, Bishop Carl Kemme) might be sensitive enough to call these mothers whose boys were sexually violated by a local priest?

And Kemme kept Fr. Larson’s passing secret until the priest was actually buried. He orchestrated it so that Fr. Larson’s death would be reported on a Friday, the day when fewer people see the news.

Is it too much to expect that a bishop might promptly be what every bishop repeatedly pledges to be – “open and transparent” about predator priests?

You learn eventually that expecting anything like normal human compassion in matters like this is too much to expect from bishops. Protect The Institution is their prime directive. If you get a bishop who does otherwise, pray for him and support him, because chances are he’s facing pressures from within the church’s leadership class that we on the outside can scarcely imagine.

The Catholic blogger Kevin O’Brien says all Catholics must do what their bishops will not:

While Catholics are looking to bishops to be representatives of Christ, that’s also what non-Catholics are looking at every one of us to be. [Emphasis his. -- RD] Become a Catholic, admit that you’re Catholic, and you’re on as much of a mission as any priest, deacon or bishop.

Every person we meet every single day of our lives is longing for something. He’s longing to see the Face of Christ.

And it’s our job to show it to him. Especially if our bishops won’t.

And we can only show others His face if it we let it shine through ours.

Along those lines, let me say that the reason I found Horace Patterson to interview in the first place was thanks to the help of a New York City priest who had learned earlier of their suffering, and reached out to comfort and to help the Pattersons. Understand: he reached out across the country to do whatever he could for a Kansas farm couple whose son had suffered and died because of the malign indifference of the Diocese of Wichita. That Catholic priest was the face of Christ to them when nobody else in a Roman collar would be. Think about that.

UPDATE: From Paul Pfaff:

It has been 30 years since I learned that my confessor was sexually abusing my sister, a dozen since I have worked with SNAP and 3 since I stopped working for the Catholic church helping victims of abuse. With all that personal experience in this mess, one of my most poignant experiences also involves Horace and Janet Patterson.

I was in a swank hotel room in downtown Dallas, June 2002, with several SNAP representatives, 15 or more bishops and cardinals, and some others. Janet pulled out Eric’s suicide note to read and excused Horace from the room – it was still too much for him to hear. She proceeded to read her son’s last testament. Raw, pure emotion. She said she wanted the church leaders to understand what sexual abuse can do, so they would stop it.

As she read I noticed a distinct difference in response to this outpouring from Janet. Most everyone gathered was crying, fully engaged and in the moment. It was so much to take in. At least 2 of the bishops present were among that group – +Lori and +Galante. Yet there were a dozen or more bishops & cardinals with dry eyes and body postures that indicated something between disconnect and contempt. These were the leaders of the Catholic Church in the US, people I’d seen interviewed on national media.

In the face a mother reading the last words of her son, these Vicars of Christ did not – could not – engage in love and compassion. They lacked the empathy to connect, the pastoral skills to show mercy, and even the human decency to pretend. Yes, they may have been in shock – it was a shocking letter – but the response was chilling. Their lack of an empathic, human response haunts me to this day.

It was repeated often in the early years of this crisis that the bishops “just don’t get it”. Amen.

UPDATE.2: From an essay Janet Patterson wrote about her son Eric:

Shortly after this, he did a complete turnabout, embracing Catholicism fervently. Daily holy hours, weekly visits to a nursing home, teaching 5th grade CCD, writing to a prisoner in Texas, continuing his pro-life activities, attending a weekly Bible study group on campus, getting confirmed – all these actions filled him with hope and enthusiasm.

Easter weekend, he proudly announced to us that he wanted to become a priest. in my heart I knew he would be a good priest, caring intelligent, and faithful to our Lord’s teachings. After graduation, he headed to the East coast as a candidate for a seminary program. He wrote letters telling of his feeling that this was truly where he belonged. The night before he was to fly home for a short visit, the directory asked him to wait in a room, that he needed to talk to him. After waiting three hours, shortly before midnight, Eric was told that he was not being accepted, that he was to take everything with him the next day, and not to tell anyone there that he would not be returning.

On the way home from the airport, Eric stunned us by saying, “They didn’t want me”. My heart lurched, my mind reeled, alternating between anger and disbelief. He was given no explanation, he said, but told us that God must want him somewhere else. Over the next few days, I watched as parishioners asked Eric where he would be studying for the priesthood. Bravely, he told each one, “They didn’t want me”, leaving them puzzled and surprised. After Eric’s death, while going through a box containing his papers, I found a paper dated a few days before his departure from the seminary. At the top of a detailed set of notes in blue ink, he had his perpetrator’s name written in red. Evidently, he had revealed his sexual abuse, leading to his rejection by the seminary. How much pain he must have gone through, finally confiding his painful secret, only to be turned away so callously. But he continued trusting in the Lord, continued teaching CCD, and making holy hours.

A few months later, Eric took a teaching position at a Catholic preparatory school two hundred miles from home. Fluent in Spanish, he taught English as a Second Language, Spanish, and religion. After over a year teaching, he had begun fasting, unknown to us, evidently trying to please God and to have a sense of control over his life. By the time we realized that Eric was in trouble physically, and mentally, he weighed only about 170 pounds, far too thin for his 6 feet 8 inch height. Entering a hospital psychiatric unit, he attempted to combat his anorexic condition and battle with psychotic depression. Asked if he had ever been sexually abused, he denied that he had. His psychiatrist was troubled by Eric’s illness, sensing that the root cause had yet to be discovered. Over a month later, Eric returned home, where we cajoled him to eat and to drink, as he had no desire to do so. Eventually, with medication, he grew stronger and healthier. For the next three years, he was a successful computer salesperson, receiving gratitude from his many customers for his courteous, professional help.

Once more, however, his weight began to plummet. Fearing hospitalization, he attempted to regain control of his life by going back on his medication. Deeply troubled, he sobbed uncontrollably one night in our living room, his best friend beside him. He dreaded hospitalization, but we succeeded in getting him admitted for treatment. As a different hospital this time, he had the good fortune of having the same psychiatrist. She was convinced there was a missing link, that some unknown cause lay at the root of his illness.

Two days later, when Becky, Eric’s older sister, visited

|

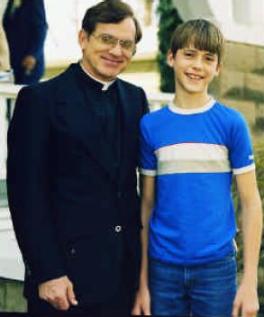

Fr. Larson & Eric Patterson

|

him in the ward, she told him that we hated his idea of God, a vengeful God Who could never be pleased. We viewed him as a loving and merciful God. Asking him if he always felt that way about God, she was surprised at his answer, “No, it all changed when I was twelve”. Then he revealed his molestations but didn’t wish to talk about it in detail. Becky consulted with his nurse, sensing that this revelation was crucial to her brother’s recovery. Later, the nurse found Eric in his room, beating his head on the floor and against the sink. After putting him in full-body restraint, the staff heavily sedated him and placed him on suicide watch. A sexual-abuse therapist began sessions with Eric, and we were hopeful that healing could begin with his long-buried secret finally exposed. He returned home about six weeks later, eventually resumed his job, and decided to move in with a friend from work. A little more than eight months after he disclosed his sexual abuse, Eric left work one Friday with no explanation, sat on the porch of his friend’s house smoking a cigarette, and then sometime that afternoon placed a gun to his head. When his friend arrived home from work, he was faced with a nightmarish scene. The police could find no suicide note, but acting on a hunch, Eric’s friend went to his computer, searched among his files, and discovered one entitled, “Hope”. Dated six days before his death, the note revealed Eric’s intense struggle to please God, yet always falling short of His expectations. With that, our handsome, intelligent, compassionate son was gone.

Another Janet Patterson essay is here. A third one is here. Read them all.

|

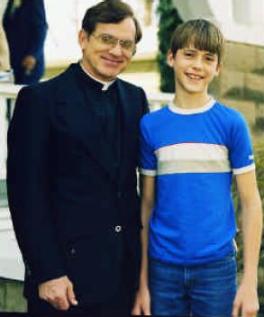

Janet & Eric Patterson

|

|