Again and Again, Local Claims of Abuse Point to One Priest, the Rev. Neil Doherty, and the Catholic Archdiocese That Protected Him

By Thomas Francis

New Times

April 17, 2008

http://www.browardpalmbeach.com/2008-04-17/news/lambs-to-slaughter/

Around the age of 8, a boy we'll call Sam made a new friend. He was a man in his early 50s, the Rev. Neil Doherty, pastor at St. Vincent Catholic parish across the street from Sam's Margate home.

Sam's family was not religious, and as the boy spent more time with Doherty, it struck his parents as odd. But the boy had trouble controlling his anger, and maybe a mild-mannered priest could be a positive influence.

In 2001, when Sam's violent tendencies landed him in a juvenile court, Doherty wrote a letter on Sam's behalf. He began by listing his curriculum vitae — his master's in divinity, psychology training at Harvard and at Loyola of Chicago, as well as counseling work at Catholic Charities and part-time private practice with Fort Lauderdale psychiatrists. He also said that over his adult life he had adopted five boys aged 6 to 12 and that all had become productive citizens.

|

| The Miami archdiocese has had the reason to doubt Rev. Neil Doherty since the 70s. |

Rescuing troubled boys was Doherty's lifelong holy mission. Sam's parents, he wrote, "can rely on me trying to be a 'good neighbor.' In this particular instance, I have become a sort of 'mentor' to their son."

The rest of the letter is full of psychological jargon about personality disorders that might be the cause of Sam's mercurial behavior and about treatments Doherty could recommend. The tone is humble, deferential, and sensitive. Doherty credits Sam's "intelligence" and calls him "a unique human being." More therapy, Doherty writes, might help Sam in "discovering and accepting his true inner self." Doherty had been happy to provide that therapy, for free.

It was the year before the sex abuse scandals erupted in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Boston. To most, priests were still trustworthy figures.

In retrospect, Sam's parents and social workers might seem nave. You can't say the same about the Catholic Archdiocese of Miami. By the time he wrote his letter about Sam, Doherty had accumulated some 30 years' worth of abuse complaints, each of which followed the same arc: A troubled boy meets Doherty for counseling and later accuses the priest of giving him drugs and then abusing him.

Sam is allegedly one of Doherty's most recent victims. By ignoring reports that Doherty was a sexual predator, the archdiocese, victims allege, made it possible for Doherty to strike again. And again.

North Miami attorney Jeffrey Herman has filed civil suits against the archdiocese on behalf of 11 of Doherty's alleged victims. Dozens of Miami archdiocese priests have been accused of sexual abuse, but none have so many victims. And considering the many boys that Doherty has counseled over the years, Herman expects that still more will surface.

If you were a parent and "your kid was having drug or behavior problems and you called the archdiocese," Herman says, "they sent your kid to Neil Doherty — which was the worst place he could go."

A native of coastal Massachusetts, Doherty moved with his family to Lake Worth in the late 1950s. After graduating high school, he enrolled in the St. John Vianney Seminary in Miami. At six foot three, Doherty made a towering figure at the altar. He seemed even taller in the vestments of a Catholic priest, with all the authority they conferred.

|

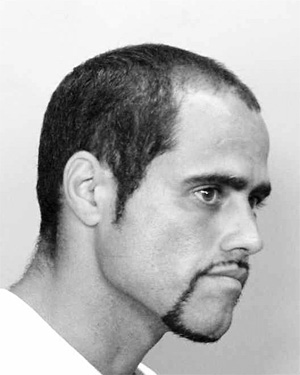

| Soler says Doherty gave him money for drugs in exchange for sex. |

Before Doherty became a priest, his superiors questioned whether he had the qualities necessary to lead a parish. In June 1968, as Doherty neared his subdioconate — the order necessary to become a priest — records show that seminary officials learned of strains between Doherty and his family. They sent him to psychological counseling for his own sake and for the sake of the church. They wanted to be sure he was fit for the priesthood.

Rev. Rene H. Gracida (who would later become the chancellor of the archdiocese), was assigned to evaluate Doherty. He ruled that Doherty was "unsatisfactory." Had the archdiocese followed its own standards, Doherty would have been turned away from the priesthood then. But for reasons unclear from archdiocese records, Doherty remained on his pastoral track.

In February 1969, as Doherty approached his ordination, Gracida authored a memo that contained a grudging endorsement. "I consider Mr. Doherty a very intelligent and complex individual," he wrote. "I cannot ascribe logical reasons for my doubts concerning his fitness for ordination." Gracida cited Doherty's "late hours and heavy drinking," but he wrote that he was most worried about the young seminarian's "obsessive preoccupation with psychology." That, Gracida mused, may have been Doherty's true calling. Though he supported ordination for Doherty, Gracida attached a caveat: "I merely wish to express serious doubts as to his fitness and as to his probable chances for achieving stability and happiness in the priesthood." A few months later, in May 1969, Doherty was ordained.

Soon he'd give his church more reason for doubt. In 1971, police raided a halfway house for troubled youth in Palm Beach County, based on allegations of widespread drug use there. Doherty had a supervising role at the halfway house; he had reported nothing about drug use. But a priest who'd been assigned to share a home with Doherty in Riviera Beach, Rev. Martin Cassidy, contacted higher-ups to advise that Doherty should be kept away from drug rehabilitation facilities.

In April 1972, Cassidy made another report, informing Archbishop Coleman J. Carroll that Doherty, then 29, had legally adopted a "young adolescent" named Gary Davis and that Davis slept in Doherty's bedroom. Judging by church records produced in civil suits, Carroll, who had held his title since the archdiocese formed in 1958, did not order an investigation or take disciplinary measures against Doherty. Shortly after Cassidy reported his concerns, however, Doherty received a new assignment to St. Anthony's Church in Fort Lauderdale.

|

| Attorney Jeffrey Herman represents alleged victims in eleven suits against the archdiocese. |

Currently under house arrest in Palm Beach County, Doherty is awaiting criminal trial on charges of sexual battery. He could not be contacted. His attorney, David Bogenschutz, declined to answer questions about Doherty's case, saying that "his side of the story will be told to a jury."

The Archdiocese of Miami did not respond to a list of questions about Doherty, citing legal concerns about pending cases. Archdiocese spokeswoman Mary Ross Agosta did furnish a statement, saying only that the archdiocese had an "on-going appeal for anyone who has been a victim of abuse by a church member to contact the archdiocese's hotline," and giving a toll-free number.

Most of the boys Doherty counseled are now men, but in the cases of complaints against the priest and the archdiocese, their identities have not been disclosed in public criminal court filings or civil suits.

One of them, whom we'll call Kevin, said he was referred to Doherty through the Catholic Services Bureau, an agency that collaborates with other social services to provide shelter and counseling for troubled children, especially those whose parents have substance-abuse problems. It's not clear from the portions of the court file available to the public how old Kevin was when he met Doherty, only that his mother was an alcoholic prone to violent rages, a source of such stress to Kevin that he had difficulty concentrating at school.

In an interview with Det. Eric Hendel of the Broward Sheriff's Office in 2005, Kevin tells of his first meeting with Doherty in 1973, the year after Doherty left Riviera Beach. Kevin was surprised that Doherty wore "sports clothes," he said, rather than the white collar and black shirt and pants priests typically wear outside church. Doherty told Kevin not to bother calling him "Father Neil," Kevin said, encouraging him to call him Gus, the name Doherty said he used with his adult friends. Kevin was even more surprised when Doherty asked if he was sexually active. "I had grown up with a rather strict Roman Catholic family," Kevin told the detective. "This, to me, was a totally new brand of priest."

The boy met with Doherty twice a week. One day, Kevin said, Doherty took out his car keys and flashed a smile. "We're going to skip a session," Kevin recalled Doherty saying. They drove to a house he remembered being "on the waterways somewhere."

Doherty opened a liquor cabinet and lit a joint. "I took a few puffs of that," said Kevin. "I was drinking bourbon. I didn't have a high tolerance at that time, so after two or three drinks I reached a point where I was getting almost ready to pass out. He directed me toward a large bedroom."

There, Kevin fell asleep, and when he awoke, "I remember feeling sexually aroused... (Doherty) was on the bed with me, performing oral sex on me."

Kevin remembered being "absolutely terrified." But he was too groggy to resist. "I was aware enough that I realized this was a priest," he said. "This was a person who had me in therapy. I was very confused and scared and stayed silent."

He told police that next, Doherty flipped him on his stomach and sodomized him.

Over the next four years, said Kevin, there were "several dozen instances of sex" between Doherty and himself. "I knew I was going to him because I was having emotional problems," Kevin said, but now those problems had multiplied exponentially. "I was confused. I was angry. I was disappointed. I was disillusioned."

Kevin finally broke off contact with Doherty around 1977, he said, after he was approached by an 18-year-old man who claimed he'd been having sex with Doherty since he was 11.

At least three other boys have accused Doherty of abusing them during his time at St. Anthony's in the 1970s.

Much like Kevin, one, whom we'll call Andy, was referred to Doherty in 1975 because he was disobeying his parents. Soon the chats with the pastor became a pleasant diversion from Andy's fourth grade lessons, he told Detective Hendel in 2005. Before long, Doherty opened the file cabinet where he kept marijuana, sleeping pills, and Quaaludes, Andy said. Andy was curious to try them and Doherty was glad to share.

Soon, their conversations broached another mysterious adult subject: sex. "He had a really bizarre attitude toward women," Andy said. "He would talk about inserting objects into their vaginas, and pouring lead into their vaginas to determine if they were a witch."

Doherty, said Andy, had a different perspective on boys. "He said the church frowned on homosexuality," Andy recalled, "but that would probably change once they discovered (that) cum tastes good... I just thought it was fascinating. Is that what the world is all about? My parents never told me about this."

Doherty invited Andy on field trips, purportedly to visit Doherty's mother in West Palm Beach. But Andy told police that Doherty's mother was never home. They would "sit around, watch TV, smoke marijuana, take pills, and drink beer," he said. Andy passed out, and when he awoke, he had pain in his rectum. This happened at least three times, he told police.

When he was 14, Andy broke into Doherty's apartment and stole the keys to the car that the priest drove. He didn't see Doherty after that.

Another boy, whom we'll call Chris, said he was 9 when he met Doherty through the Catholic Services Bureau. Like Andy and Kevin, Chris was referred based on behavior problems in school. When, during their sessions, Doherty asked about homosexuality, Chris expressed disgust, saying he'd kill any man who made a move on him. An adult neighbor had already assaulted him.

Chris had formed a drug habit before he became a teenager. Now he bounced between Boys Town in west Miami and juvenile halls. Doherty always seemed to turn up. He encouraged Chris to call him "Gus" too. Chris thought it was cool that this priest had posters of rock bands on his walls. "He was teaching me to drive a car — you know, the things that a boy would want a father figure to do," he told a detective. In his early teens, he visited Doherty at a home in Coconut Grove, he said, and the priest gave him marijuana.

When he was 15 or 16, Chris escaped from a reform school, and Doherty offered him a place to stay. After a night of drinking and smoking pot, Chris passed out. When he woke in the middle of the night, Doherty was molesting him. "I just laid there frozen," he told police. "This person I had trusted with my entire life... violated me, and there is nothing I could do about it."

After Doherty finished, Chris lay awake listening. "I waited until he went to bed. I got up and I left, and I never saw him again." In 1979, Chris was sent to prison for seven years.

Neither Chris nor Andy told anyone about the abuse, they said — not their parents, not even their friends. "It's not a very cool thing to talk about," says Andy, who agreed to be interviewed recently by phone. "When you're a young person, you want to be accepted, to not have people look at you like you're a weirdo." Having recently turned 40, Andy evidently has overcome that fear and is suing the archdiocese.

In 1979, another abuse report surfaced: a boy who says Doherty drugged and molested a 16-year-old friend. Representing the victims at a deposition last year, Herman handed Rev. Monsignor Tomas M. Marin, the chancellor of the archdiocese, a copy of the April 1979 memo that contained the accusation. Herman asked Marin what the proper response to that report should have been.

"Investigate the allegations and see if they were true or not," Marin replied.

Herman pounced. He reminded Marin that the report ought to have been given to the police, not investigated internally by the church. But Marin disagreed: "There is no policy in 1979 that we had to report it," he said.

But there was a law: Florida Statute 415.504. The statute requires persons with knowledge or suspicions of child abuse to report them to the Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services. "What if I told you there was a law that said you had to report it?" Herman asked. "Would that change your opinion?"

"It would possibly change my opinion," Marin answered.

The report of the 16-year-old, plus another allegation that Doherty molested a 6-year-old, prompted an investigation by the archdiocese. Ultimately, Marin's own review of archdiocese records found no interviews of victims or of Doherty — only a consultation with a psychiatrist and a background check to ascertain if Doherty had ever been arrested in Broward County (he had not). The investigation was closed.

If you've been abused by a priest in South Florida, Jeffrey Herman is the guy you call. Herman grew up in a Jewish family in the eastern suburbs of Cleveland. He's in his 40s, has a weightlifter's shoulders and an eager, energetic demeanor. On days he's not in court, he ditches the suit for jeans and vintage T-shirts. He relishes media coverage, which for him is a good way to attract new clients.

So far, Herman has settled five civil cases involving the Rev. Neil Doherty and has six more pending. He has also sued the archdiocese based on reports of abuse by 15 other priests.

The Catholic Church has become a jackpot for Herman, who reasons that it's the church's own fault. "From my perspective, secrecy is a hallmark of the church," he says. "You have this imbalance of power where priests are the parish's connection to God. They have a mandate to keep secrets, to protect the church from scandal. And that was their priority — not protecting children."

In the course of bringing his lawsuits, Herman has learned much about the psychological effects of sexual abuse, how it shames victims into feeling as though they're controlled by forces stronger than themselves. Since the criminal courts' statute of limitations has lapsed for victims who were abused in the '70s and '80s, the civil courts are the only place they can seek justice.

"By coming forward and filing a civil lawsuit, they're taking power back in their lives," says Herman. "Victims have told me this is part of the healing process. By holding the church accountable, they realize, 'This is not my fault.'"

In sexual abuse cases involving priests, the Catholic Church has traditionally used a Canon Law standard to judge guilt or innocence called "moral certainty." It's similar to a criminal jury's instruction to convict only when evidence suggests "guilt beyond a reasonable doubt." Handled internally by the church, abuse complaints boil down to a priest's word against a child's. In Doherty's case, those children were almost always from checkered backgrounds. That appears to have made it difficult for the church to establish moral certainty of Doherty's guilt.

Herman argues that even if the individual kids who claimed Doherty abused them lacked credibility, the sheer volume of reports, combined with their similarity — drugged, then raped — established a pattern that made Doherty's guilt inescapable. "If you're not going to remove a priest until you have moral certainty, you're going to expose kids to a grave risk," says Herman. "In my opinion, the only thing certain about Doherty is that he was going to abuse more kids."

As he shuffles into a conference room in a jail jumpsuit, Jorge Soler no longer looks like the boy he was when he met Doherty. He doesn't even look like the young man in the mug shot, his goatee finely trimmed, from when he was booked at the Turner-Guilford-Knight Correctional Center in Miami. Now, aged 32, his thick beard covers his whole face.

Soler grew up in Little Haiti before the area's cultural renaissance and the emerging Design District. In the early 1980s, drugs and crime made the sidewalks a menacing place for boys to play. He was the youngest of five children in a poor family. Soler had tried drugs even before he met Doherty in 1983 when he was 9. The priest had been sent to Soler's home as an outreach counselor to help his brother Jose, who was three years older and had a penchant for violence. Jose would be placed in foster care. Doherty placed Jorge, who was also troubled, in Miami Bridge, a youth shelter then on NW South River Drive.

With other boys, a lengthy interval passed before Doherty, the friend and counselor, became an abuser. But Jorge Soler remembers his abuse starting immediately.

Doherty would pick Soler up at Miami Bridge and take him shopping for new shoes, shorts, and jeans before they were joined by two other boys, both named Victor. One was of Colombian descent, the other Puerto Rican. Doherty served them drinks that Soler thinks were drugged, possibly with Valium or Quaaludes, a popular sedative at the time. "He turned me on to drugs by not telling me he was giving me drugs," Soler says with a bitter smile.

Relaxed by the drug, Soler and both Victors were assaulted. On some occasions another priest — a junior pastor at St. Mary's Cathedral, possibly a seminarian, was also present. That priest took nude photographs of the boys and joined Doherty in raping them, he says.

Soler remembers riding in Doherty's car, the priest drunk or high on Valium, scanning Biscayne Boulevard for a boy who would turn a trick. Doherty had no interest in men. "If they were over 18, he didn't want to mess with them," he says.

Sometimes when he visited Doherty he'd be given $200, enough for a big drug score in the '80s. Other times, "it was hard to get a dollar out of him," he says, even when Soler was willing to trade sexual favors.

The abuse first came to light in 1983. During a counseling session with Dr. Simon Miranda, a court-appointed therapist, Soler started weeping and finally described how Doherty abused him. Archdiocese documents show that Miranda reported Soler's allegation immediately to Archbishop Edward McCarthy, but no investigation occurred.

Four years later, Soler himself sought out Doherty at the archdiocese pastoral center. "I wanted money for drugs," Soler explains. "He had said if I ever needed money to call him, but he was ignoring me."

Doherty was not at the pastoral center. Desperate, the 15-year-old boy resorted to blackmail. He informed a nun, Sister Joyce Newton, that he'd had sex with Doherty and contracted a venereal disease. Newton phoned Doherty, who instructed her to give Soler money from the center's petty cash drawer just to get rid of him.

This time there would be an investigation, by archdiocese chancellor Gerard T. LaCerra.

Documents subpoenaed in a civil suit Soler has filed against the archdiocese suggest that LaCerra's investigation was biased. As Soler's attorney, Herman calls the investigation "a fraud" and "a sham."

A month after Soler made his charges at the pastoral center, LaCerra wrote a letter to Archbishop McCarthy detailing Doherty's explanation for the incident. Doherty claimed he didn't know Soler except as a youth staying in a rooming house with other "clients" Doherty says he was trying to help. "This guy, if he was the same one I recall, was on 'crack' and acting crazy already," Doherty wrote. "The people who lived there wanted to get rid of him, because he was stealing from everyone."

The priest also attacked Sister Newton's credibility. He told LaCerra that the nun was sexually attracted to him and so "frustrated" by his lack of interest in her that she accused him of being gay and hating women. Soon after, Doherty fired Newton on grounds she was "mentally ill and severely unreliable." He claimed she had conducted interviews of pastoral center staff who encountered Soler during his visit, but "that detailed account was taken from my desk around the same time I fired Sr. Joyce Newton."

LaCerra attached his own letter to Doherty's, marking it "strictly personal and confidential." In it, LaCerra explained to the archbishop that Soler was "an acknowledged homosexual prostitute and drug dealer" and that Newton was a "seriously ill person" who was part of an effort to "defame Fr. Doherty."

In July 1987, four months after he spoke dismissively of Soler's report to the archbishop, LaCerra began his formal investigation. His report indicates that during one of his visits to the Soler household, Jose called. He was put on the phone with LaCerra, who asked him about his younger brother Jorge's clients. "Father Neil" is the first client Jose mentioned. The report also cites an interview in which Jorge told investigators of occasions when Doherty became drunk and had sex with him as well as the Victors and several other boys.

LaCerra never reported these allegations to the police, and no archdiocese records have materialized suggesting Doherty was disciplined. Instead Doherty continued his pastoral work counseling boys.

In August 1992, Archbishop McCarthy forwarded a letter to LaCerra. The letter opened with a now familiar refrain: "Our son was given drugs, Quaaludes in excess — and then raped by Father Neil Doherty, presently pastor of St. Vincent Parish in Margate, Fla."

The letter tells of a boy we'll call Tony, who had been an A-student at a Fort Lauderdale high school in 1978 when his parents went to meet with Doherty about counseling their son. Pastor Doherty at St. Anthony's, "absolutely charmed us," Tony's parents wrote. "So you can imagine how easy it was for Father Doherty to hide behind his authority as a priest and... to take advantage of a mentally ill, gullible 17-year-old boy. It was leading a lamb to slaughter."

In the letter, and in a later meeting with LaCerra, Tony's parents alleged that Doherty brainwashed their straight son into believing he was gay. On at least one occasion Doherty took Tony to a Palm Beach motel, his parents said, where he gave the boy beer, marijuana, and Quaaludes, then raped him after he fell asleep.

Six months before Tony was to graduate, he dropped out of high school. Two months after that he ran away from home. Tony's parents wouldn't see him again for five years. He moved out of the region, became deeply depressed, and was leading what his parents called a "hand-to-mouth existence."

In 1994, LaCerra wrote a memo recounting a phone conversation he had with Tony in which LaCerra offered counseling. Tony rejected the offer on grounds that archdiocese counseling was what had created his problem in the first place.

Doherty was sent for psychological treatment at the Institute for the Living, a resort-like clinic in Hartford, Connecticut, that's a frequent destination for troubled priests. The archdiocese's ostensible goal was to determine whether Doherty had the psychological makeup to continue as a pastor, or if he should be removed. Dr. Richard Bridburg recommended the archdiocese issue a "temporary suspension from [Doherty's] duties while further investigation is taking place."

In December 1992, Chancellor LaCerra wrote a letter to Bridburg in which he said Bridburg's ruling was "at variance with my remembrance of our (previous) conversation." LaCerra recalled that a less formal solution had been agreed on, and that Doherty would simply "take time off to work on personal issues." LaCerra's letter contained a chilling passage that could have exposed LaCerra and Archbishop McCarthy to criminal charges: "If perchance your report would ever be placed under subpoena, the archdiocese could look quite negligent for not having immediately removed Fr. Doherty from his pastoral assignment."

Herman points out that in legal terms, "negligence" is the knowledge prior to a crime's being committed. "This is only negligence," says Herman, "if (Doherty) abuses again. LaCerra basically expects him to abuse again."

Ultimately, LaCerra convinced Bridburg to revise his recommendation, and Doherty was allowed to choose his own counselor — in this case, a friend who questioned why Doherty was being "targeted" by false claims. The friend suggested the archdiocese accept Doherty's "candid and forthright assertions of his innocence."

Apparently, it did just that.

As for the claims made by Tony, memos by LaCerra to the archbishop show the chancellor characterizing the family as extortionists and deriding the credibility of Tony's claims based on his refusal to accept counseling. After Tony's family threatened to bring their story to the media, LaCerra negotiated a speedy out-of-court settlement. In 1994 the archdiocese paid Tony's family $50,000 in exchange for a promise not to sue.

Assistant State Attorney Dennis Siegel seems to take Herman's view on church officials' handling of the complaint. In 2003, as Siegel prepared a criminal case against Doherty, his research turned up evidence that could support a criminal case against the archdiocese as well. In a letter he informed the archdiocese that only the statute of limitations prevented him from filing criminal charges against it.

By then it was too late to prosecute LaCerra, who died in July 2000 of a heart attack while aboard a plane bound for Israel. McCarthy died in June 2005. Doherty, in the meantime, returned to St. Vincent in Margate to resume counseling boys.

By the late 1990s, Doherty had every reason to feel invincible. A slew of boys had come forward to report abuse but not a single charge had stuck.

At roughly the same time that the archdiocese reached its settlement with Tony's family, it was welcoming a new archbishop, Rev. John C. Favalora, who had previously held that position at dioceses in Alexandria, Louisiana, and St. Petersburg, Florida.

LaCerra's role as chancellor had passed to Msr. Marin, who was greeted by a disturbing report from a group of parishioners at St. Vincent in Margate. The group had written to Archbishop McCarthy alleging that Doherty was stealing from the church till and that he had placed a known male prostitute on the payroll. Since McCarthy had ignored the report, the group hoped Favalora would investigate.

The archbishop assigned it to Marin, who met with the group. Marin testified that during that meeting the male prostitute wasn't mentioned. In 1995, he drafted a letter, to be read at a Sunday service and bearing Favalora's signature, describing how the archbishop had examined the parishioners' report but that two audits found no evidence of financial impropriety. "Likewise, (Favalora) examined personal accusations made against Father Doherty and found them baseless," the letter continued — an apparent reference to the report involving the male prostitute.

But in depositions last year, Marin said the investigation only focused on the financial charges. He claimed to be unaware of the allegation about a prostitute. Though Favalora became archbishop in December 1994, the same month that the archdiocese settled its case with Tony's family, both Favalora and Marin claimed ignorance of the $50,000 payment.

Favalora testified that he did not remember receiving a letter alerting him to Doherty's relationship with a male prostitute. If he had, he would have passed it to Marin, he said. "As Archbishop of Miami, I presume that the people that I delegate the matters to looked into the things that needed to be looked into," he said.

"And do you know whether they did?" Herman asked.

"No, I don't," Favalora replied.

In Msr. Marin's deposition, Herman asked whether the settlement, combined with the long history of abuse allegations in Doherty's personnel file, ought to have warranted a more thorough investigation of the Margate pastor.

"Hindsight is 20/20," Marin replied.

That doesn't bring an ounce of comfort to Sam, who agreed to speak to New Times on condition of anonymity. At a coffee shop in Margate not far from where he says he first met Doherty, he speaks through a clenched jaw on a mid-March afternoon. He was in fourth grade and playing football near his home across the street from St. Vincent's landscaped courtyard when he stepped away from the game to smoke a cigarette. The 8-year-old saw Doherty's tall form step out of a car and walk toward him.

"I hid my cigarette — like, cuffed it," says Sam, "and (Doherty) says, 'No, man, if you want to smoke it's not that big of a deal.' He was trying to be the cool adult. He was trying to gain my trust that way — and it worked."

The two struck up a friendship, and it progressed quickly. "We would talk for hours and hours about my beliefs," says Sam. "He is a very intelligent man. He was my friend at first. Then he was my mentor. Then he was my father. And it went from that to the abuse."

It would be a while before Sam's parents learned of their son's new friend, and when they did they didn't approve. But Sam still visited Doherty almost every day, he says.

The priest would pour Sam a soda in a red plastic cup. In a 2005 interview with a police detective, Sam recalled that on one occasion after drinking the soda, "I passed out, and I walked out of (Doherty's) house later not remembering what had happened." He had pain in his rectum. Asked by the detective to elaborate, Sam responded irritably, "I felt as if I'd been fucked in my ass."

Sam found a wad of money in his pocket which he also didn't remember. The rest of the details mirror the familiar stories of boys 20 years before: Alcohol and drugs leading to blackouts and waking to Doherty in the midst of his assault.

It was the end of Sam's childhood. He was no longer interested in BMX racing or playing war games with kids from the same cul-de-sac. He was depressed, and Doherty recommended drugs. "I'd get angry all the time, and he said to drink beer and smoke pot because it would lessen my anger," says Sam. But those chemical effects made him yearn for uppers, "which is when I took coke."

Sam's family was not wealthy. His allowance was $5 a week, and he dressed in hand-me-down clothes his older brother got from a thrift store. But he says Doherty was willing to finance the boy's drug habit, which had progressed to heroin. When he was placed in a juvenile home for misbehavior, Doherty visited him there. Sam lost touch with Doherty when he was sent to prison for possessing an illegal weapon and dealing drugs.

Thanks in part to the counseling he received while incarcerated, Sam says, he came to understand how Doherty's abuse had affected his life — how it was at the root of his depression and his chemical addictions.

Sam has a vivid memory of a night not long after his release from prison when he was walking along NW 18th Street near St. Vincent Church. "I was trashed... fucked up on Oxycontin," says Sam. "And he approached me." By then Sam had taken to carrying a knife to defend himself in the rough crowds where he moved. "I was so filled with rage I pulled my knife. I shined the blade in the streetlight so he could see it. I said, 'If you come near me, I'll kill you.'"

Doherty backed off. Sam hasn't seen him since. If there's a next time, it may be in a criminal trial.

In 2002, after the scandal in the Boston archdiocese, Msr. Marin conducted an inventory of abuse charges against active priests in the Miami archdiocese which finally led to Doherty's placement on administrative leave. In 2004, Doherty retired.

Today St. Vincent is led by Rev. Joseph Maroor, who conducts Mass with a cheerful, earnest demeanor. On a Sunday in March, about 400 parishioners fill the pews of the T-shaped church. In his sermon, Maroor speaks about how in the moments before Mass he entered the sacristy and saw an elderly man holding a sign. "It said, 'Don't tell God how big your problems are. Tell your problems how big your God is.'" Maroor beamed. "What a wonderful truth!"

It'll take a very big God to get the Catholic Church out of its current fix. Herman is not allowed to say how much his clients have received in settlements so far, nor would he estimate how much he expects to win on unsettled cases. He says only that "millions" would be a fair characterization.

Kevin, the boy referred to Doherty for counseling related to his alcoholic mother, told no one about having had sex with Doherty until a few years ago, when he saw an article about another victim who was suing Doherty. Kevin told police that in the decades since the abuse, he's thought about Doherty every day.

Andy, another '70s-era victim once impressed by Doherty's willingness to talk to him about adult subjects, has moved away. "It really ruined my life for a long time," he says by phone. Like other abuse victims, Andy has battled addiction and had trouble keeping jobs and building relationships. Now, he says, he's clean, employed, and engaged to be married.

Jorge Soler's life after Doherty has followed a more tragic arc. He has accumulated a long rap sheet of drug offenses and currently awaits trial on charges of credit card and car theft. Soler says his attorney has negotiated a plea deal that would give him about five years in prison. A recovering crack cocaine and heroin addict, Soler says he's made progress in drug treatment; he's holding out hope for a program that would allow him a measure of freedom in exchange for drug screening

Soler is a Baptist now. That faith, plus his family and a 10-year-old daughter, are enough to stave off the thoughts of suicide that have plagued him for as long as he can remember.

Does he think Doherty's religious faith was genuine?

Soler shakes his head. "That's a disguise," he says of the priestly garments Doherty wore. "He doesn't care about nothing. Going around raping little kids: That's his belief."

Two other alleged victims whose accounts were not included in public files are in jail too, one for grand theft and armed burglary and the other for murder.

For Sam, who once flashed his knife at the priest, the shame of having been raped by Doherty made him resolve to kill himself a few years ago. Until then, he had never told a soul about what happened, he says. But something prompted him to call a friend and tell her about Doherty's abuse. He said he planned to commit suicide. And for the first time in a decade, Sam wept.

His friend convinced Sam not to follow through, to live, if only to see Doherty receive justice. Today Sam is the one victim who appears in the criminal case Assistant State Attorney Dennis Siegel is building against the priest. A conviction could put Doherty, now 63, in prison for the rest of his life.

"It's pretty much retribution," says Sam, taking a drag on a cigarette. "There's no making it OK. I don't think if he was beaten in public and dragged naked through the streets so people could throw rocks at him it would be OK."

Yet seeing Doherty punished would make it just a little easier for him — and, Sam guesses, other victims — to get through the day.

Sam hasn't had a good night's sleep in ten years, he says. Doherty appears in his nightmares constantly. In dreams he acts out elaborate revenge fantasies: In one, he decapitates Doherty with a rusty shovel.

He's hardened himself, he says. When strangers say hello he ignores them. He still carries weapons, though now only a bat and a nightstick instead of guns or knives. Recently he broke off ties to a white supremacist group. Sam has met ruthless people, but he calls Doherty "the only monster I've ever met in my life."

With evident pride, Sam says "I'm not a nice person." He describes himself now as an agnostic. Asked whether he believes in Heaven and Hell, he says, "I would like to believe there's a Heaven, but I doubt it." Eyes flashing, he adds, "And if there's anything like Hell, then I'll see him there."

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.