By David Yonke

Toledo Blade [Toledo OH]

July 15, 2007

http://toledoblade.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20070715/NEWS10/707150304/-1/NEWS

Minnesota attorney Jeff Anderson stood before reporters on the lush green lawn of the Lucas County Courthouse five years ago today and announced he was suing the Toledo Catholic Diocese and former priest Leo Welch.

The high-profile court action by the nation's top attorney for victims of clerical sexual abuse brought to Toledo the national scandal that erupted in Boston in January, 2002, and spread like a dark cloud across the country.

It has been a tumultuous five years for church leaders and lay persons as more than two dozen people sued the Toledo diocese, alleging they were sexually molested as children by priests, deacons, or other church leaders.

The Toledo diocese, which has 325,000 members in 19 counties, also has endured a number of other high-profile controversies including the murder conviction of one of its priests, Gerald Robinson; public protests over the moving of the historic Lathrop House; financial woes leading to staff layoffs; the closing of 17 parishes, and a dispute over the reassignment of the Rev. Thomas Leyland from St. Rose Parish in Perrysburg.

|

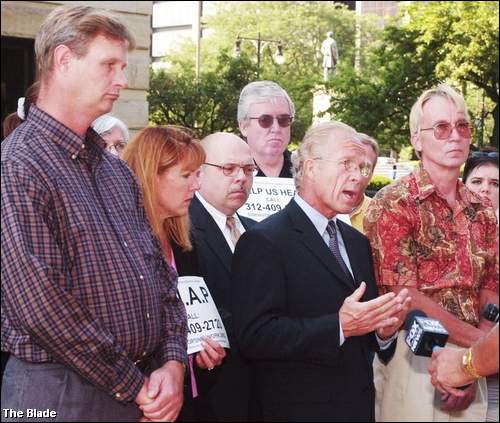

| Attorney Jeff Anderson, center, fi led a lawsuit in 2002 on behalf of Harold Lee, left, and George Keller, right, who were abused as children by Father Leo Welch when the priest served at Immaculate Conception Church in Bellevue, Ohio. |

Mr. Anderson's lawsuit, filed on behalf of two Welch victims, was among 19 that were settled out of court in August, 2004. The diocese paid $1.19 million to 23 victims in amounts ranging from $4,500 to $150,000.

Forty priests in the Toledo diocese have been accused of abusing children between 1950 and 2006, according to the latest figures from the diocese. Updates are published periodically on the diocese's Web site, toledodiocese.org.

|

Church response

Local church leaders have implemented a wide range of programs and policies since 2002, updating their guidelines and instituting new programs, many of which were mandated by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops at its meeting in Dallas in June, 2002.

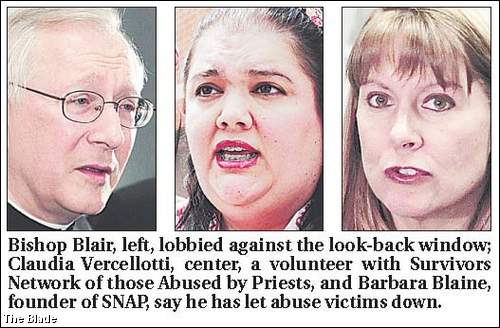

Bishop Leonard Blair, who came to Toledo from Detroit in December, 2003 - 10 months after the death of longtime diocesan leader Bishop James Hoffman - was among those who approved the Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People.

Bishop Leonard Blair was in Europe last week and unavailable for comment, but the diocese's spokesman, Sally Oberski, said the bishop "repeatedly says that he will do 'everything humanly possible' to protect youth from clergy sexual abuse. I believe that this adherence to policy has permeated through the staff and clergy of our diocese."

The Toledo diocese was one of the first in the nation to set guidelines for dealing with sexual abuse by clerics when it adopted a policy in 1988.

|

| Toledoan Tony Comes was profi led in the 2005 Oscar-nominated documentary ‘Twist of Faith’ and became one of the most visible figures in the national clerical sex abuse scandal. |

Among the steps taken since 2002 cited by Ms. Oberski are the creation of a review board that hears allegations of abuse; a pastoral response team that provides pastoral care for both victims and offenders; a code of pastoral conduct for priests, deacons, pastoral administrators, staff, and volunteers; extensive background screening, training, and fingerprinting measures, and mandatory attendance for church employees and volunteers at Protecting Youth Workshops.

Twice, in 2003 and 2004, the Toledo diocese was found to be in compliance with the Dallas Charter after independent audits ordered by the conference of bishops.

'Nothing has changed'

Mr. Anderson and several abuse victims interviewed by The Blade said, however, that they feel much more needs to be done to bring clerical offenders to justice and to protect children in northwest Ohio.

"The good news is that several survivors have surfaced in Toledo," Mr. Anderson said last week. "The bad news is that in Toledo, by reason of the laws of Ohio and the intractability of the hierarchy there, nothing has changed. It is business as usual."

|

According to Mr. Anderson, who has filed more than 2,000 lawsuits against Catholic dioceses nationwide, the primary obstacle faced by abuse victims in Ohio is the statute of limitations.

The state legislature last year extended those time limits in which abuse victims can file lawsuits from two years to 12 years after a person turns 18 but rejected a proposal to waive the statute for a year to allow lawsuits by people abused as long as 35 years ago. "The Ohio bill is a crazy bill that doesn't mean a thing," Mr. Anderson said. "In California, a look-back window did pass and as a result California has become progressive and permissive in allowing survivors to come forward."

Delaware passed a similar bill last week that included a look-back window, he said.

"That window is absolutely vital, and a repeal of the statute of limitations or the creation of a look-back window is what's necessary to expose the problem and bring the perpetrators to justice," he said.

| Significant local developments in the clerical sexual abuse scandal: March, 2002: Frank DiLallo, Toledo diocesan case manager charged with dealing with allegations of abuse, is quoted in The Blade as saying that in his six years on the job there have been "absolutely no allegations of priests abusing children." April, 2002: Former Toledoan Teresa Bombrys sues the Toledo diocese claiming she was abused as a child by the Rev. Chet Warren, a priest in the Oblates of St. Francis de Sales religious order serving in Toledo. In March, 2005, Bishop Leonard Blair, from the pulpit of St. Pius X Church, apologizes to Ms. Bombrys for the abuse. June, 2002: The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, meeting in Dallas, adopts a "zero-tolerance" policy for abusive priests as part of its Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People. June, 2002: Bishop James Hoffman permanently removes four priests from ministry for allegations of sexual abuse of minors. July, 2002: Jeff Anderson holds a news conference outside the Lucas County Courthouse announcing a lawsuit against the Toledo diocese and former priest Leo Welch. August, 2002: The Toledo Catholic Diocese signs a voluntary cooperation agreement with the Lucas County Prosecutor's Office pledging to open all its files involving allegations of child sexual abuse. September, 2002: The Blade reports that former priest Dennis Gray, then working as a dean at Rogers High School, had been accused of sexually molesting teen boys before leaving the priesthood in 1987. A letter from the diocese to one victim states that Gray "has admitted to us he is guilty of child abuse." The ex-priest is removed from his Toledo Public School position and eventually sued by nine men claiming he molested them when they were children. October, 2002: Toledo diocesan priests Stephen Stanbery and Patrick Rohen call for Bishop Hoffman's resignation over his handling of the clerical sexual abuse crisis. December, 2002: In a three-part investigative report, The Blade reports 24 cases of child-abuse involving priests and church workers in the Toledo diocese between 1960 and 1994. February, 2003: Bishop James Hoffman dies of cancer at 70, having led the Toledo diocese since 1981. September, 2003: The Toledo diocese announces restrictions on counseling sessions for victims of clerical sexual abuse. The policy sets a 25-session cap unless further treatment is approved by a panel. October, 2003: The Vatican announces that Auxiliary Bishop Leonard Paul Blair, 54, of Detroit, will be the next bishop of Toledo. He is installed Dec. 4. January, 2004: The Toledo diocese is found to be in full compliance with the 2002 Dallas Charter, according to an independent audit ordered by U.S. bishops. May, 2004: The diocese reports that it is laying off 11 employees and cutting some programs because of a $600,000 shortfall in its $6.7 million fiscal budget. January, 2005: Twist of Faith, a documentary about Tony Comes abuse by Toledo ex-priest Dennis Gray, premieres at the Sundance Film Festival in Utah. It later is nominated for an Oscar and is broadcast on HBO. August, 2004: The diocese settles 19 sexual abuse of minors lawsuits, paying out $1.19 million to 23 victims. December, 2004: The Toledo diocese is found to be in compliance with the Dallas Charter after a second independent audit. March, 2006: The Ohio legislature passes a bill extending the statutes of limitations for civil suits involving sexual abuse victims but rejects a provision for a one-year window allow suits for incidents dating back as much as 35 years. November, 2006: The Catholic Conference of Ohio announces a $3 million fund to provide counseling for victims reluctant to ask the church for help. Recipients of the funds must agree not to sue the church. |

Mr. Anderson's 2002 news conference involved a lawsuit he filed on behalf of George Keller and Harold Lee, two men now in their 50s who were abused as children by Father Welch when the priest served at Immaculate Conception Church in Bellevue, Ohio.

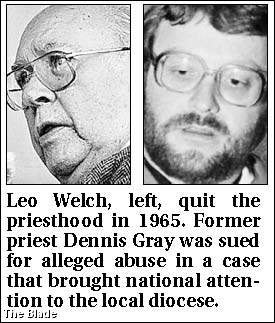

Father Welch, who quit the priesthood in 1965, told a Blade reporter in 2002 that he had molested an unspecified number of boys, saying, "I was sick," and that it was "a case of sexual experimentation."

Mr. Lee, now 55 and living in Roanoke, Va., said last week that he had hoped his lawsuit would spur changes in the state's statutes.

"I was 9 years old when I was abused," he said. "Even in my 20s, I was not able to talk about it. In fact, I would never have talked about it, except George needed some help."

Mr. Keller, the first Welch victim to go public, said he knew of four dozen other boys who had been invited for weekend getaways to Father Welch's cottage in eastern Lucas County, where the abuse occurred.

When no other victims came forward, Mr. Lee felt he had no choice but to join Mr. Keller in the lawsuit and to participate in the news conference, where he slipped away from the cameras at one point to fight back a flood of emotions.

"I was in a situation where I did not want to be," he said. "It was hard."

He said he received a monetary settlement from the diocese that was "six figures" but said the negotiations with the church's attorneys were traumatizing.

"I just got the feeling that not just in the Toledo diocese, but all over the country, that every diocese was just trying to pay off people to shut them up," Mr. Lee said. "I lost my faith and they didn't do anything to help me get it back. I felt like it was just big business, dealing with a customer."

He said he had hoped to be kept informed of, and perhaps participate in, church efforts to draft policies for monitoring offenders, but was never given the opportunity. "I don't know whether the settlement and the work to go through that was worth it," Mr. Lee said. "It just stirred up a lot of bad emotions and quite frankly, you think that you've buried things in your head long enough that the pain isn't there. But going through that, it sure awakened a lot of bad emotions."

Accountability

Catherine Hoolahan, a Toledo lawyer who has represented more than a dozen victims in lawsuits against the diocese, said none of her clients wanted to sue.

"In every case, my clients said, 'If I could have gotten criminal prosecution, I wouldn't have done this.'

"On the one hand, it's not about the money. On the other hand, it is from a symbolic standpoint because money is all we've got, it's all we can ask for," Ms. Hoolahan said.

She said her clients were disheartened to find that the average settlements in Toledo were one-third those in Cleveland.

"They were not in it for the money, but money is the only yardstick we can use. My clients thought the diocese of Cleveland cared three times as much as the diocese of Toledo," Ms. Hoolahan said.

Tony Comes, one of nine victims who sued former Toledo priest Dennis Gray for alleged abuse, was profiled in the 2005 Oscar-nominated documentary, Twist of Faith, which brought national attention to the local diocese.

Mr. Comes, a former Toledo firefighter, became one of the most visible figures in the national clerical sexual abuse scandal.

He said last week that he had hoped his story would help bring about positive changes in Toledo.

"I staunchly was going to change the church from the inside out: 'Nobody's going to run me out of there,'•" he said.

But he has since given up on that quest. "Since Cardinal Ratzinger was appointed Pope [in April, 2005], I don't see a light at the end of the tunnel. I've become a member of [nondenominational church] CedarCreek with my wife."

He still follows closely the diocese's dealings with abuse victims, and feels the results have been consistently disappointing.

"I don't think the Toledo diocese has really done anything other than window dressing. They exhort I don't know how many platitudes, saying they care, but time after time they have defended the indefensible and let the wallet determine what they do," Mr. Comes said.

Defending the diocese

Ms. Oberski said diocesan leaders have become "hyperalert and hypervigilant" since 2002 in their efforts to protect youth and to respond to allegations against diocesan employees or volunteers.

All clergy and personnel are expected to follow Ohio laws on reporting abuse allegations to civil authorities, she said, and the pastoral response team recently created "a healing packet" that contains "pertinent information on grief, anger, depression, sexual abuse, prayer cards, and Scripture to aid victims in their healing process."

The diocese regularly states that anyone with allegations against a priest, employee, or church volunteer should contact the diocese and report the allegations to civil authorities, Ms. Oberski said. She also said the nine members of the pastoral response team watched Twist of Faith together "in order to sensitize themselves to the pain of victims."

One of the factors that led Mr. Comes to quit the Catholic Church was Bishop Blair's lobbying efforts against Senate Bill 17 and its look-back window.

The Ohio Conference of Catholic Bishops actively opposed the window, saying it was unconstitutional, and proposed instead a civil registry on which the names of alleged perpetrators would be listed.

"I made eight visits to Columbus and they just gutted that bill," Mr. Comes said. "It seems no one wants to hold anyone accountable."

Trying to heal

Extending the statutes and opening the look-back window also were key concerns of Claudia Vercellotti, local coordinator of SNAP - the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests - who estimated she made 100 trips to Columbus to meet with legislators and testify before committees.

"This was my vehicle for healing," said Ms. Vercellotti, 37, whose alleged abuser was a diocesan lay leader. "If we could get the law changed, then we could keep other kids from becoming victims. We can't protect kids in the here and now until we clean up the past."

Ms. Vercellotti first stepped before the cameras saying she was an abuse victim at the 2002 courthouse news conference, weeks after undergoing neck surgery following a car accident. Wearing a thick neck brace, she said she was reluctant to speak out at first and gave only her first name to the media.

She has since become the most visible and outspoken victims' advocate in Toledo, working as an unpaid volunteer for SNAP.

She said her role has been difficult, taking a toll on her job and her personal life. But she remains an active and faithful Catholic seeking to bring about reform from within the church.

"If you had told me six years ago, 'Claudia, you're going to be public enemy No. 1 in the diocese office,' I would never have believed it," she said. "The cost has been significant, but the choice is either to be at home and be miserable or to stand up and do something about it."

At the 2002 news conference, Mr. Anderson said he hoped the Welch lawsuit would provide "leverage" to get diocesan officials to negotiate. He called for local church leaders and victims advocacy groups to sit down together and create a plan for "prevention, healing, and reconciliation."

Ms. Vercellotti said she is still waiting to meet with Bishop Blair, despite writing him more than a dozen times.

Barbara Blaine, a Toledo native who founded SNAP in 1989 and serves as national president of the group which has 5,000 members, also feels Bishop Blair has let down victims of clerical sexual abuse. "Bishops are working harder than ever at public relations, but fundamentally they still protect their secrets more than they protect their flocks," Ms. Blaine said.

Contact David Yonke at: dyonke@theblade.com or 419-724-6154.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.