The Sins of Our Fathers

Sex Abuse: What the Diocese Knew and Didn't Tell You

By Dave Janoski djanoski@leader.net

Times Leader

July 9, 2006

http://www.timesleader.com/mld/timesleader/14998976.htm

[See other articles in this feature:

- The

Shame of the Diocese: Allegations? Move Father Caparelli. More Allegations?

Move Father Caparelli. Convictions? Keep Quiet, by Dave Janoski, Times

Leader (7/9/06)

- Priests

Feel Hurt, Angry, Guilty by Association: When Scandal Breaks, Say Innocent

Pastors, They and Flock Get Caught in Turmoil, by Mary Therese Biebel,

Times Leader (7/9/06)

- Bill

Aims to Loosen Limits on Suits: Statutes of Limitations on Sex-Abuse Cases

Often Leave Victims with No Options, by Dave Janoski, Times Leader

(7/9/06)

- Crimes

and Accusations, Times Leader (7/9/06) [summaries, assignments, and

photos of accused priests]

- A

Church Re-Educates Itself: Changing Attitudes: The Catholic Church Has

Mandated Special Training to Recognize Sexual Abuse and Abusers, by

Mark Guydish, Times Leader (7/9/06)

- Morning

Note from the Newsroom: the Church Series, by Matt Golas, Times Leader

(7/11/06).]

For years, Roman Catholics in the Diocese of Scranton didn't know that

priests accused of sexually abusing minors continued to preach in their

churches, hear their confessions and teach their children.

But their bishops knew.

As early as the 1960s and as late as 2002, the Scranton Diocese knowingly

employed priests who had been accused of sexual misconduct, according

to court documents and diocesan statements.

|

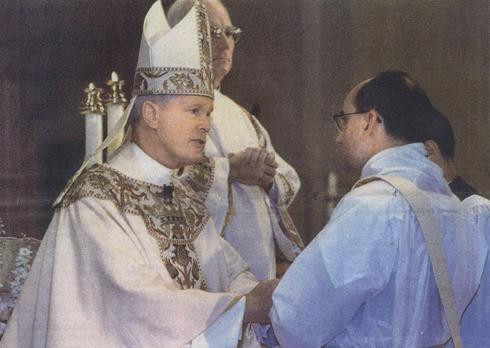

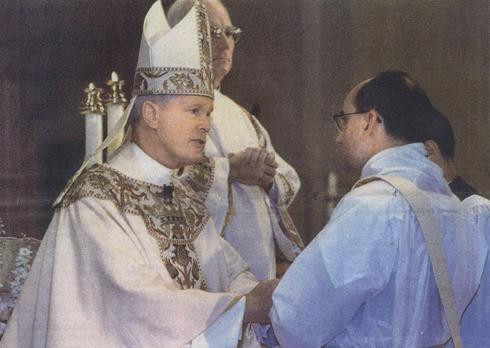

| Bishop James C. Timlin ordains Christopher

Clay in 1998. Clay, one of at least 25 priests in the Scranton Diocese

accused of sex abuse since 1950, has been barred from public ministry.

Timlin, now bishop emeritus, has been accused of failing to protect

his flock from abusive priests. Times Leader file photo. |

A Times Leader investigation, including interviews with alleged victims

and a review of eight lawsuits, some of which had gone largely unreported,

revealed allegations that church officials disregarded warnings of abuse

or merely reassigned accused priests, sometimes with dire consequences.

Bishop Emeritus James C. Timlin – a diocesan official since 1966 – was

personally aware during his administration as bishop from 1984 through

2003 that at least five of his priests had been accused of sexual misconduct

with minors, according to lawsuits and diocesan statements.

Yet they remained in their parishes and posts, some going on to abuse

other children.

What is a tragedy with

the Catholic Church is how many cases were terribly mismanaged,

where a bishop or religious superior said 30 or 40 years ago, 'OK.

You're forgiven. Don't do it again.'

Thomas Plante

Psychology professor at Santa Clara University who has written two

books on abuse by priests |

In 2002, Timlin removed five priests from active ministry because of

a new, nationwide "zero-tolerance" policy adopted by American

bishops in reaction to a nationwide wave of abuse allegations. The policy

required the removal from ministry of any priest who had been proven to

have engaged in sexual misconduct at any point in his career.

In interviews with the Times Leader shortly before the policy was adopted,

Timlin maintained it should not be applied to priests who had been accused

in the past, received treatment and returned to ministry without further

problems.

Such priests were similar to others who had been treated for alcoholism

and returned to duty, he said.

In addition to Timlin, at least two other Scranton bishops, both now deceased,

were aware of accusations against priests, but allowed those priests to

continue ministering to local Catholics, according to lawsuits.

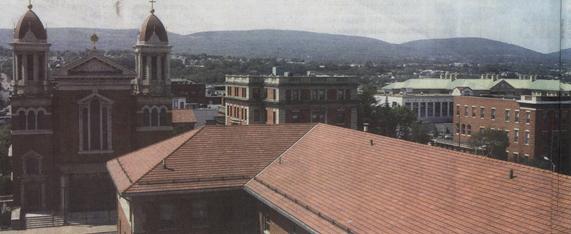

|

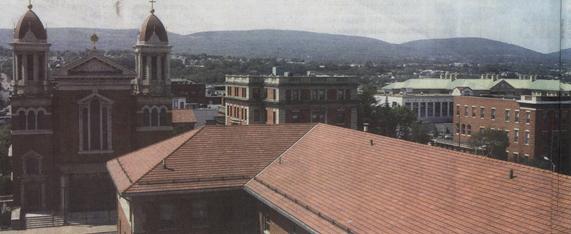

| The church hierarchy runs the diocese

from a cluster of buildings near St. Peter's Cathedral on Scranton's

Wyoming Avenue. The cathedral is at left. Times Leader staff photo

/ Aimee Dilger. |

Timlin, through a diocesan spokesman, declined to be interviewed for

this story. In an e-mail message, spokesman William Genello said the diocese

would not answer any of the Times Leader's questions about its handling

of abuse allegations:

"I must say your approach to this issue is curious – focusing on

cases that are decades old and priests who have been deceased for many

years? I certainly hope this does not reflect any personal or institutional

animosity toward the Catholic Church."

Times Leader President and Publisher Patrick McHugh defended the paper's

approach, pointing out that the investigation had uncovered new details

of already publicized cases and revealed some cases that had not been

reported before.

"While many of the cases and priests cited in the series are indeed

well in the past, a clear pattern of actions and behavior has emerged

on the part of people whose responsibilities should have led them to act

more in the interests of parishioners and those harmed. Local church leaders

appear to have failed their flock," McHugh said.

"To suggest any animosity on the part of the Times Leader or its

staff is absurd. Many of the most senior managers of the paper, including

the editor and me, are of the Catholic faith. This series will stand on

its merit."

Numerous accusations

At least 25 priests serving in the Scranton Diocese have been accused

of having sexual contact with minors since 1950, according to diocesan

reports.

The diocese has never released the names of all of the accused, but has

acknowledged sexual misconduct accusations against eight priests whose

names became public because they were arrested or sued or because their

removal from ministry became public knowledge. The Times Leader has uncovered

the names of three more, all deceased.

In 2004, the diocese reported

that 25 of its priests were accused of misconduct involving 46 minors

between 1950 and 2002. In a press release that year, the diocese said

charges against 15 of the 25 priests were "founded," but it

did not define the term or describe how a case was determined to be "founded."

A diocesan spokesman recently declined comment on the report.

The diocese's data were gathered for a nationwide study

commissioned by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops that concluded

4 percent of American priests serving between 1950 and 2002 had been accused

of abuse. The percentage in the Scranton Diocese was 2.86, based on the

diocese's figures.

The 2004 study, compiled by the John Jay College of Criminal Justice using

reports submitted by Catholic dioceses and religious orders around the

country, cited other studies to suggest that abuse of minors by priests

might be less prevalent than abuse by those in other professions or American

adults at large.

"If you take studies of school teachers, that research suggests there's

about 5 percent of school teachers who have sexual contact with a minor

child," said Thomas Plante, a psychology professor at Santa Clara

University, a Jesuit university in California, who has written two books

on abuse by priests.

It's the church's mishandling of abuse cases in the past, not the numbers,

that has fueled the nationwide abuse scandal, he said.

"What is a tragedy with the Catholic Church is how many cases were

terribly mismanaged, where a bishop or religious superior said 30 or 40

years ago, 'OK. You're forgiven. Don't do it again.'

"It's the secrecy. It's the cover-up. It's the leadership making

tragic mistakes."

Costly claims

The Scranton Diocese's handling of accusations during the past 40 years

has proven costly.

Since 1995, diocesan attorneys have negotiated settlements in at least

four cases involving priests accused of sexual contact with minors, at

a cost of more than $835,000, the diocese says. Three other suits are

ongoing.

Many of the settlement details – and pertinent diocesan documents – remain

sealed from public view because of confidentiality agreements between

the diocese, other defendants and plaintiffs.

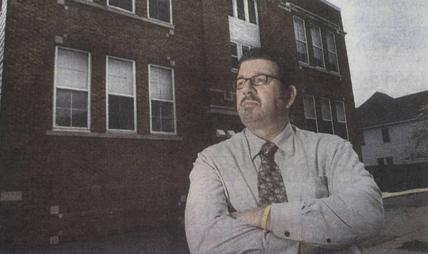

|

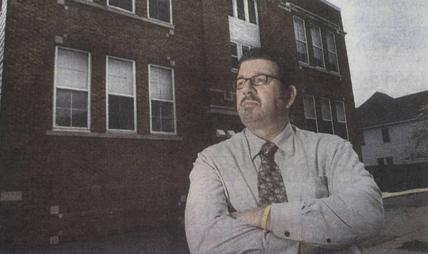

| Thom Pesta in the former schoolyard in

Luzerne where he says he was fondled by his pastor, Father Lawrence

P. Weniger, decades ago. The school, Sacred Heart, has moved to a

different location. Times Leader staff photo / Clark Van Orden. |

But a Times Leader review of available documents and interviews with

victims indicate the Scranton Diocese's reaction to abuse charges has

often paralleled that of the Philadelphia Archdiocese, which was the target

of a stinging grand jury report last year.

The grand jury, which found 63 priests in the Philadelphia Archdiocese

had been credibly accused of abuse, said that diocese covered up abuse

allegations, failed to adequately investigate them and kept dangerous

priests working in jobs where they had access to more potential victims.

In its investigation of the Scranton Diocese, the Times Leader found:

• In 2000, Bishop Timlin and his then-vicar

for priests, Father Joseph R. Kopacz, were informed by other diocesan

clergy of suspicions that Father Albert M. Liberatore Jr.,

a Duryea pastor, was sexually abusing a teenage boy, according to a suit

filed in U.S. District Court in Scranton. Liberatore denied the allegations

and accused his accusers of misconduct, the suit said. Timlin never brought

the allegations to a diocesan review board set up to consider such cases

and told Liberatore and the other priests to "put the issues behind

them," the suit claims. The victim's family was not told of the allegations

and the abuse continued for two years, the suit said. Liberatore was arrested

3 1/2 years later, after Timlin retired, because of information uncovered

by a private investigator working for the diocese. Liberatore, who pleaded

guilty in the case and was sentenced to 10 years probation, is a defendant

in the victim's federal suit along with Timlin, Kopacz and the diocese.

• In 1999, church

officials in Minnesota informed Timlin, Kopacz and Auxiliary Bishop Joseph

Dougherty of allegations that Father Carlos Urrutigoity,

the head of a conservative religious society in Pike County, had engaged

in improper conduct with a Minnesota seminarian, according to a federal

lawsuit. The diocese later said the facts in the case were inconclusive.

Urrutigoity and another priest in the Society of St. John in Pike County,

Father Eric Ensey, were later accused of sexual misconduct

with a student at St. Gregory's Academy in Moscow, where the society was

temporarily housed. Ensey initiated the sexual contact in 1997, when the

boy was a 16-year-old junior at St. Gregory's, according to the suit.

In December 2001, a former associate of the society publicly revealed

the allegations against Urrutigoity and Ensey. They were suspended from

ministry by the diocese the following month. The alleged victim from St.

Gregory's sued the priests, Timlin and the diocese, among others, in March

2003. The case was settled for $454,550 last year, with the diocese paying

$200,000. Timlin's successor, Bishop Joseph Martino, withdrew the diocese's

approval for the society to operate here. It has since moved to Paraguay.

• In April 1988, Timlin received anonymous

letters alleging a Towanda priest, Father Robert Brague,

46, was involved in a relationship with a teenage girl from his parish,

according to Brague's deposition in a civil suit. Brague had initiated

sexual activity with the girl in 1987 when she was 17. Brague met with

Timlin in April 1988 and denied the allegations. Timlin took no action,

Brague testified. Four months later, after the girl became pregnant, Brague

admitted to the allegations.

He moved to Florida, where he continued to serve as a priest until his

death in 1997. The diocese and Brague settled the victim's suit in 1995.

The terms were not disclosed.

• In 1968, Bishop J. Carroll McCormick –

and Timlin, who was the bishop's secretary – were informed by a Hazleton

police officer that Father Robert N. Caparelli had been

accused of molesting two altar boys in the city. Caparelli, who denied

the charges, was sent to a Catholic rest home for a month. There he was

evaluated by a psychologist who urged the diocese to investigate the allegations

further and wrote that if they were true, the priest would probably molest

again. Caparelli was quickly reassigned to a Lackawanna County parish

and continued to serve in local schools and churches until his arrest

on sex abuse charges in 1991, during Timlin's administration as bishop.

By then he had molested four more boys, maybe more, according to his diocesan

file and lawsuits. In the 1970s, Caparelli admitted to his superior at

an Old Forge church that he had groped at least one boy there. It is unclear

if that pastor, William Giroux, ever alerted the bishop or other diocesan

officials. Caparelli died in prison in 1994, presumably because of AIDS.

• In 1962, a 12-year-old altar boy at St.

Therese's Church in Kingston Township, Thomas Harris, told Father Michael

Rafferty, a priest at his school, Gate of Heaven in Dallas, that his parish

priest, Father Francis Brennan, had fondled and sodomized

him, according to a lawsuit. Rafferty met with Harris' parents, but refused

to alert then-Bishop Jerome D. Hannan, the suit said. When approached

directly by Harris' parents, Hannan assured them Brennan would be "taken

care of," the suit said. Brennan was reassigned to a convent, but

not punished in any way, the suit said.

He remained an active priest until his death in 1974. At least one other

man claims he was sodomized by Brennan at St. Therese's during the same

period, when he was 14.

Harris could not be reached for comment.

Rafferty, retiring as pastor of Our Lady of Sorrows Church in West Wyoming,

declined comment.

Shroud of secrecy

The Scranton Diocese has consistently fought to keep information on accusations

against its priests from becoming public.

In many cases, it has asked judges to seal from public view all or some

documents in lawsuits filed by alleged victims of abuse.

"There are confidentiality issues with the records, although plaintiffs

are allowed to have them," said James E. O'Brien Jr., a Scranton

attorney who represented the diocese in all the lawsuits reviewed by the

Times Leader.

"There are accused that have been exonerated. There are some victims

that deserve some privacy."

But church critics say such secrecy is aimed primarily at protecting dioceses

from legal liability.

David Clohessy, national director of the Survivors Network of Those Abused

by Priests, said the 2002 scandal in the Boston Archdiocese, where 141

priests were accused of abuse, was uncovered only because victims' attorneys

successfully pushed for court orders to obtain diocesan documents, which

were then made public.

"That's what every bishop is afraid of," Clohessy said. "A

bishop does not want to take the witness stand and reveal how much he

knew and how little he did about these criminals."

In at least one case, the Scranton Diocese offered a cash payment to an

alleged abuse survivor in exchange for keeping silent.

William Nothoff says he was forcibly sodomized in the rectory at St. Therese's

Church in Kingston Township in the 1960s by Father Francis Brennan, whose

alleged abuse of Thomas Harris during the same period is the focus of

an ongoing lawsuit.

Nothoff told no one of the abuse for three decades, but he said it contributed

to "rough spots" in his life, including substance abuse problems.

In the mid-1990s, Nothoff told his story to a church employee in Arizona,

where he lives.

"I was literally falling apart. It felt like a grenade had gone off

in my head," he said in a recent phone interview.

The church employee contacted the Scranton Diocese, which began paying

$120 per week for counseling for Nothoff and offered him a $5,000 settlement,

provided that he never go public with his story.

Nothoff never signed the settlement and didn't take the $5,000. During

a 1995 trip to Northeastern Pennsylvania for a family wedding, he gave

an interview to the Times Leader, which printed his story, without revealing

Brennan's name. The diocese promptly stopped the counseling money, he

said.

In an interview with the Times Leader at the time, Monsignor Neil Van

Loon, diocesan chancellor in 1995, described the $5,000 offer as an act

of "mercy or kindness," because there was no way to prove or

disprove Nothoff's allegations.

Van Loon said Brennan "had a good record with nothing to indicate

anything but a clean record."

But Van Loon said the diocese was concerned Nothoff might sue, even though

the statute of limitations would have expired decades earlier:

"We're not going to waste $5,000 and then have him attempt to sue

us. It would be public, we would have to get legal counsel ... and for

what end?"

It's unclear if Van Loon or other diocesan officials in the 1990s were

aware of the accusations against Brennan allegedly made to Bishop Hannan

by Thomas Harris and his parents in 1962.

Van Loon, now a diocesan official stationed near Williamsport, declined

comment through a diocesan spokesman.

Trying to help

Some alleged victims of abuse by priests say they aren't interested in

suing, but are motivated to go public to protect children from similar

abuse.

Thom Pesta said that until the nationwide priest abuse scandal broke in

2002, he thought Monsignor Lawrence Weniger was just a "lone, sick

man."

"I always thought it was an isolated event. Then I found out it was

not."

Pesta said he and other boys at Sacred Heart School and Church in Luzerne

were fondled by Weniger more than 40 years ago. The incidents happened

on the playground, in the sacristy and on church grounds, Pesta said.

"We had a little support group. We laughed about it. I don't know

if it was because it was funny."

Pesta said he told his parents about Weniger, but they didn't believe

him.

"I refuse to believe the bishop didn't find out about this. I find

it hard to believe that for all the kids it happened to, this never came

out."

Pesta said he believes the incidents contributed to his withdrawn nature

as a child and might be one of the reasons he has shunned organized religion

as an adult.

"It's not like my world crumbled. But I spent much of my time alone.

"I had led a tortured childhood but the rest of my life was fine."

Pesta grew up to work as a musician and as an operations director at Walt

Disney World in Florida. He now works at Guard Insurance and lives in

Kingston.

Weniger died in 1972.

When the allegations of abuse by priests in Boston and other dioceses

began receiving media attention in 2002, Pesta asked for a meeting with

then-Bishop Timlin about Weniger.

In an interview with the Times Leader from that period, Timlin acknowledged

there had been allegations about Weniger after his death:

"I knew him, but we never knew anything about this. There have been

several people who have accused him. Because of all the publicity, I did

talk to somebody about that. I apologized. I never knew anything about

it."

Pesta recalls his meeting with Timlin somewhat differently.

"He basically said, 'I'm sorry you left the church.' He was certainly

not admitting or denying anything.

"He said what you would expect a politician to say."

THE SERIES

These are times of transition for the Roman Catholic Diocese of Scranton.

The center of gravity in the 11-county diocese – home to 355,000

Catholics – is shifting eastward to the fast-growing Poconos. While

many churches in Luzerne and Lackawanna counties have been forced to close

or merge because of shrinking congregations, others are being revitalized

by an influx of Hispanic parishioners.

The number of priests has declined by half since 1960, adding more pressure

for consolidations and closings and expanding the roles of lay church

volunteers.

Catholic parents who grew up in an era of inexpensive and thriving elementary

and secondary schools now find their choices limited, as the diocese closes

school after school, citing financial pressures and declining enrollments.

Also, the diocese’s leadership finds itself confronted with allegations

that it mishandled sex abuse charges against some of its priests, with

victims’ advocates calling for legal changes that could open the

diocese to increased liability.

Today, the Times Leader begins a four-part series on a church challenged.

Today: The Scranton Diocese stands accused of not doing enough to protect

parishioners from abusive priests.

Next Sunday: The dwindling number of priests puts more pressure on those

who remain and provides new possibilities and responsibilities for lay

volunteers.

Sunday, July 23: Falling enrollment and financial pressure have whittled

away at the diocese's school system, and more school closings are likely.

Sunday, July 30: What will the diocese of the future look like?

LEARN MORE

• For more information on the issue of sexual abuse by priests,

go to the following Web sites:

www.snapnetwork.org:

Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests

www.usccb.org/nrb:

U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops National Review Board

www.bishop-accountability.org:

A large collection of documents related to abuse by priests

www.virtus.org:

National Catholic Risk Retention Group Inc.

www.dioceseofscranton.org:

Diocesan site contains information on programs to prevent abuse

Times Leader Associate Editor/Investigative Dave Janoski may be reached

at 829-7255.

|