By Sam Hemingway

Burlington Free Press [Vermont]

April 30, 2006

http://www.burlingtonfreepress.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?

AID=/20060430/NEWS01/604300313/1009/NEWS05

The year was 1972 and the newly appointed bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Burlington, the Most Rev. John A. Marshall, had a decision to make.

The Rev. Edward Paquette, employed in parishes near Fort Wayne, Ind., wanted to transfer to the Vermont diocese, ostensibly so he could be closer to his aging parents, who lived in eastern Massachusetts.

Marshall was inclined to approve the transfer, writing to Paquette at one point in response to Paquette's inquiry that "Naturally, I am very anxious to have the assistance of as many quality priests as may be possible."

|

|

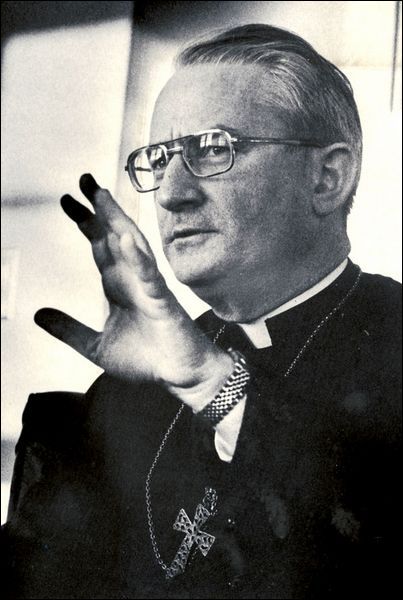

Bishop John Marshall, seen here in 1982, transferred pedophile priests who went on to reoffend. Photo by The Free Press |

Paquette had molested boys at parishes in Indiana and Massachusetts, and Marshall knew it, church records show. The bishop also knew Paquette had received several weeks of electric shock therapy to treat what was described at the time as "this sickness of homosexuality."

Persuaded that Paquette was cured, Marshall agreed to the transfer. In doing so, he overrode an initial recommendation from Indiana that Paquette work in an institutional setting away from children. Instead, he placed the priest at the Christ the King parish in Rutland.

That decision, just six months into his 21-year tenure as Vermont's bishop, was the first of a series of misjudgments Marshall would make regarding priests accused of sexual misconduct, decisions that have since cost the diocese an estimated $1.5 million in damage awards.

According to documents on file at Chittenden County Superior Court, that figure may soon be millions of dollars more.

Jerome O'Neill, the attorney for 16 victims of priest abuse who have lawsuits pending against the diocese, asked Judge Ben Joseph last year to order the diocese to set aside $20.5 million in church assets to cover potential damage awards in nine of the cases, seven of them involving molestation claims against Paquette.

The judge declined to do so at the time, but lawyers for the diocese have publicly acknowledged the diocese under Marshall's leadership did not adequately protect altar boys from being molested by Paquette and listed it as a key reason for agreeing this month to settle the first of 11 cases filed by alleged victims of Paquette.

"The diocese will not assert it did not know of Father Paquette's past problems," the lead diocesan attorney, David Cleary, told prospective jurors in the initial case, brought by Michael Gay of South Burlington, just before it was settled. "I agree the diocese should have been more careful."

In a statement released April 19, the day the diocese reached its $965,000 out-of-court settlement with Gay, the diocese said it would raise the needed money by taking out loans and not tap collections for the church or donations to the annual Bishop's Fund, which helps pay for church social services and education programs,

Last week, though, diocesan officials were busy huddling in a series of meetings to address the financial questions raised by the result in the Gay case. Gloria Gibson, the diocesan spokeswoman, declined to elaborate on the substance of the meetings.

Bishop Salvatore Matano, writing a week ago in the latest edition of the Vermont Catholic Tribune, lamented the pain suffered by the victims of priest abuse and acknowledged the tough times the diocese faces in light of the settlement in the Gay case.

"I must seek solutions in these cases which do not jeopardize the services rendered to our people through our diocesan agencies," he wrote. "For us all, our faith is tested throughout this entire painful ordeal." Matano declined a Free Press interview request. Marshall retrospective

Marshall, a Worcester, Mass., native who was chancellor of the Rhode Island diocese before his appointment as bishop of the Burlington diocese in late 1971, was an intensely private man, said a former vice chancellor of the diocese who worked under him.

"He was hard to get to know because he was so private," said William Corcoran, who resigned his priesthood in 2001 and now works for a large nonprofit corporation in Washington, D.C. "He was extremely dedicated, though, a very hard worker."

Monsignor John McSweeney, the diocesan chancellor at the time Paquette was hired, called Marshall a great bishop.

"He was a great guy doing the best he could with what he had," McSweeney said. He declined to comment on the Paquette case.

Corcoran, who worked under Marshall during the bishop's last six years in Vermont, said he was not involved in any of the personnel matters that have since come to haunt Marshall's legacy. Marshall departed the Vermont diocese in 1992 to lead the Springfield, Mass., diocese. He died in 1994.

"Bishop Marshall considered priest conduct issues a private matter between a bishop and the priest," Corcoran said. "He attended to those things personally and did not involve a large number of staff members."

Corcoran said Marshall viewed cases of priest sexual misconduct as moral lapses rather than psychological problems. "Bishop Marshall didn't quite know how insidious pedophilia was, or how to root it out," Corcoran said.

Diocesan documents made public after the Gay settlement bear out Corcoran's analysis of Marshall.

On Nov. 13, 1974, just 23 days after being informed Paquette had molested two boys at a Rutland hospital, Marshall wrote Paquette a letter urging him to take advantage of the treatment he was getting but also informing Paquette he would soon get another parish assignment.

"Your sincere desire to serve as a priest is beyond question in my mind," Marshall wrote.

Even in his last letter to Paquette, dismissing him in 1978 following fresh claims of child molestation at Christ the King parish in Burlington, Marshall was praiseworthy.

"You have so many good qualities as a human being and as a priest, that the people and priests of this diocese, including myself, have come to regard you with affection," Marshall wrote in the April 18, 1978, letter.

A review of the Paquette documents also shows that the diocese and Paquette's doctors viewed Paquette's sexual misconduct with the altar boys not as pedophilia but as "this sickness of homosexuality," as one personnel-board review of Paquette described it.

The documents indicate Paquette was treated for his "sickness" periodically throughout his time as a priest in Massachusetts, Indiana and Vermont, usually by doctors who were religiously affiliated with the church. In nearly every case, the reports that came back to Marshall and his colleagues in the other two states were upbeat.

"He is basically a good man, trying to fulfill role expectations, and I trust with continued support from all of us and continued spiritual direction, his prognosis will be optimistic but guarded," the Rev. Thomas Kane, a clerical psychotherapist, wrote Marshall three weeks before additional revelations about Paquette forced Marshall to dismiss him.

Paquette, now 77, never returned to the ministry after his departure from Vermont. He lives in Westfield, Mass. Unswerving loyalty

Over the years, according to church and court documents, Marshall grew increasingly determined to resolve cases of sexual misconduct by priests internally and, if at all possible, without revealing to the Catholic community the real reason priests who had engaged in sexual misconduct were suddenly no longer around.

Paquette's abuse of altar boys was not disclosed to parishioners in Burlington when he was dismissed in 1978. And, when the Rev. Alfred Willis was removed from St. Anthony Church in Burlington for molesting boys in 1979, Marshall chose not to warn the priest of St. Ann's parish in Milton, where Willis was sent, about Willis' past conduct.

Instead, the parish priest, the Rev. Philip LaMothe, had to learn about Willis' past from some of his own parishioners after molestation claims involving boys at the Milton church surfaced in 1980.

"The pastor advised the bishop that some parishioners of St. Ann's parish had learned there were allegations of similar activity while Willis was at St. Anthony's parish in Burlington," said a statement signed by Cleary in the diocese's $170,000 settlement with Robert Douglas of Burlington, a Willis victim, in 2004.

"It was at that time that Bishop Marshall then advised the pastor at St. Ann's parish regarding information he had received from certain of the parents at St. Anthony's parish in 1978," the statement said.

Marshall also personally put pressure on the Chittenden County State's Attorney's Office not to prosecute Willis at the time, according to O'Neill, who represents two other alleged Willis victims in cases now pending in Chittenden County Superior Court.

O'Neill, speaking on the day of the Paquette settlement, said Susan Via, a deputy state's attorney at the time, has claimed in a court deposition that Marshall tried to appeal to the Catholic backgrounds of several of the prosecutors in trying to get Willis off the hook.

"Her testimony, under oath, is that Bishop Marshall not only tried to convince the state's attorney not to prosecute, but on top of that, he made mention of the fact that prosecution might constitute the sin of scandal," O'Neill said.

Via, who now lives in Arizona, did not respond to a telephone request for an interview. Then-Chittenden County State's Attorney Mark Keller, now a judge, said in an interview he does not recall the meeting with Marshall the same way.

"If someone had made a threat like that, I think I would have remembered it," Keller said. "My memory is that this was like a thousand other meetings where someone came in to convince us to do something they wanted."

Keller said Willis was not prosecuted because police could not produce a cooperating witness to help make the prosecution's case. The diocese eventually stripped Willis of his clerical status and he now lives in Leesburg, Va.

In 1990, Marshall had another brush with prosecutors when the Rev. Michael Madden was charged with two counts of sexual assault involving boys in Barton. Madden was serving as parish priest at St. Paul Church in Barton and St. John Church in East Albany at the time.

Then-Orleans County State's Attorney Phil White, aware of police evidence that Madden had molested boys at other parishes, wanted to interview Marshall under oath at a deposition about evidence Marshall and the diocese had of other misconduct by Madden.

Marshall, through his attorneys, vehemently objected to the proposed deposition by arguing that under the Constitution, the church was immune from state scrutiny.

Judge Dean Pineles ultimately ruled Marshall could provide the information requested under seal, but Marshall never did so, according to White. The case was resolved when Madden pleaded no contest to two charges of lewd and lascivious conduct.

Madden later settled a civil suit brought by one of his Barton victims for $162,500. Madden died in 2000. Marshall, who banned Madden from priestly duties after the Barton incidents, declined to discuss the case at the time, despite the media attention the case had received. The faithful cope

For the Catholic faithful, the prospect of their church's having to come up with millions of dollars to settle claims of long-ago sexual misconduct by priests is troubling.

"It's not like the diocese has an inexhaustible supply of money," said David Austin, who lives in Vergennes and serves on the parish council of St. Peter Church in town. "I and others like me are ultimately going to bear the financial burden for this."

Austin, however, said he holds no ill will toward Marshall.

"Bishop Marshall made what he believed in his heart was the best decision at that time," Austin said. "We're not privy to all the conversations from back then, and the paper trail in the court doesn't tell the whole story."

He also questioned whether the Catholic Church is being unfairly singled out by the courts for the misdeeds of former priests, while other institutions with employees who engaged in abuse of children have received less scrutiny.

Catholic officials note that at a pre-trial hearing before the Paquette case was settled, Judge Joseph made a point of wondering why the diocese had chosen March, just weeks before the Paquette trial was scheduled to begin, to announce plans to consolidate parishes in Vermont.

"I thought it was curious ... there was a month in which there was extensive publicity about the church trying to close certain parishes," Joseph said, according to a transcript of the March 26 hearing. "It was just a curious time for this publicity to be released."

Cleary, the diocesan attorney, declined to speculate on Joseph's remark, but acknowledged in an interview on the day of the Gay settlement that he was disappointed with some of Joseph's rulings in the Paquette case.

"There were a series of pre-trial motions that not only complicated our ability to defend this case, but in some areas I would say probably made it impossible," Cleary said. "It was not exactly what I'd call a level playing field."

Contact Sam Hemingway at 660-1850 or e-mail at shemingway@bfp.burlingtonfreepress.com

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.