Shining light on a cover-up

A priest and a prosecutor detail how it happened

By Michael Newall

National Catholic Reporter

April 28, 2006

http://ncronline.org/NCR_Online/archives2/2006b/042806/042806a.php

[See also the editor's note by Tom Roberts, A

look into a hidden culture; NCR's editorial in the same 4/28/06 issue of NCR; author Mike

Newall's account below of the interviews he conducted for this article;

and our Web edition of the Philadelphia

Grand Jury Report.]

The call comes on a Sunday morning. It's a sex abuse victim named Billy

on the tail end of a three-day bender of booze and cocaine. He is hysterical,

ranting, raving, saying he wants to die. Will Spade, a 41-year-old assistant

district attorney, is at home in the quiet, leafy Philadelphia neighborhood

of Chestnut Hill, enjoying a lazy morning with his wife and two young

children. Up to this point, September 2002, Spade's involvement with the

recently impaneled grand jury investigating Philadelphia clergy abuse

has been confined mostly to conducting preliminary interviews, sorting

through mounds of procedural paperwork or sitting through strategy prep

meetings.

|

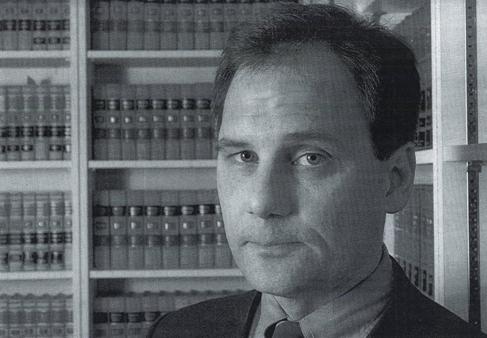

| Will Spade, former Philadelphia assistant

district attorney. Photo by Michael T. Regan |

Spade and another assistant district attorney race over to Billy's mother's

house located in a modest, working-class section of Northeast Philly.

They find Billy sitting on the front steps, his head buried in his hands,

a cigarette burning between his fingers, his crying girlfriend standing

over him while his toddler daughter runs through the shaded yard.

"Do you want to see what they did to me?" Billy shouts, jumping

to his feet. "I'm an animal. I don't want to live anymore."

Billy's brother is also there.

"You're going to the hospital to get help," yells Billy's brother.

"If not, then get out of here. We don't want you around. We all [were

molested] by this guy. You just got to deal with it."

Billy is an intimidating man. He looks like a bodybuilder, and he stalks

around the front yard, punching a metal vent on the side of the house,

bloodying his knuckles. Billy wishes for a knife to stab himself in the

neck, and he speaks of the Indian warrior Crazy Horse who earned honor,

Billy says, by taking revenge against those who stole from him. Billy

promises revenge against the former cardinal of Philadelphia who he says

protected the priest who stole his innocence.

Spade and his partner try their best to calm Billy.

"Think of your daughter," Spade later recalls telling Billy.

"Think of how good it feels in your heart when you hold her in your

arms."

"You can't understand what I've been through," shouts Billy.

"You haven't walked in my shoes. My world is dark now."

"There is a good person inside you, Billy," says the other prosecutor.

"That's why you reached out to us this morning."

Soon, Billy relents and collapses to the pavement. Billy, whose name has

been changed to protect his confidentiality, is involuntarily committed

to a hospital that evening.

Spade goes home to his wife, unable to fully convey the emotions of what

happened.

* * *

The next morning Spade arrived at his office on the 10th floor of the

district attorney's office feeling groggy and dazed. John Delaney sat

talking with two detectives. Delaney is a small, wiry man with the look

of an aging bar brawler. Thirty-three years old, he works odd jobs whenever

he can get them -- mostly roofing or construction -- has two children

he rarely sees and a mother who lives 15 minutes away from him that he

hasn't talked to in three years. He struggles with cocaine and feels vulnerable

when he sleeps, rarely resting straight through a night. His face is lined.

His eyes are jumpy.

Delaney has decided to step forward and tell his tale of abuse. It is

a secret he has kept hidden for more than two decades. At times, he thought

he'd found places dark, deep and empty enough to bury it. But it was always

there, boiling beneath the surface, soothed only by violence, drugs and

self-degradation. He told his ex-girlfriend once. But that was a long

time ago. They were lying in bed, and he was wasted. "I'm going to

tell you this," he recalls telling her, "and then I don't want

to ever hear about it again." She listened and seemed sympathetic

and never spoke of it again.

The two men sat down in a conference room toward the back of the office.

Spade tried to make Delaney feel comfortable, realizing how difficult

it must be for him to share such details with a stranger. As Spade remembers

it, Delaney shifted in his seat, his hands fidgeted, his eyes darted around

the room. He seemed to still feel shame over what happened to him as a

child.

| 'It was like working in a factory,' said Will Spade. 'And in this

factory was a conveyor belt of damaged people. Every day it was another

damaged person.' |

He was a scrawny, shy kid, he told Spade. His father left when he was

an infant and his mother married again, a cop. The family lived on a small

street. Everybody was Catholic and everybody's parents were cops, firemen

or teachers. It was sometime in the fifth grade when the new priest, Fr.

James Brzyski, visited the classroom asking for volunteers for the Altar

Boy Guild. Brzyski was tall and heavy-set with a shock of blonde hair

and a charismatic personality. John enjoyed being an altar boy, often

serving two or three Masses each Sunday. Once, on a special holy day,

he said, he was awarded the privilege of standing on the altar beside

the former Philadelphia archbishop, Cardinal John Krol. [Note from BA.org:

See the Philadelphia

Grand Jury Report's materials on Rev. James J. Brzyski.]

Brzyski befriended John's mother and became a frequent guest at the Delaney

home, chatting up John's stepfather on police affairs -- Brzyski's dad

was also a cop -- and always bringing along some little toy or item of

clothing for John and his sister. John's parents felt honored that a priest

would be lavishing them with such attention. To them, it was a gift, a

blessing bestowed. In their eyes, a Catholic priest was Christ's representative

on earth.

This was a notion new to Spade, who grew up in a devoutly religious Lutheran

household. In his family, Lutheran ministers were respected in the same

fashion as a particularly good teacher or doctor or a judge. They were

not held in the same reverence as Catholic priests. But this almost blind

fealty to the parish priest is a story Spade will hear over and over again

as he interviews victims of clergy sex abuse for the next two years.

Soon, Brzyski began inviting the family over to the rectory. As the grand

jury report detailed, they were humbled by the opulence: the gold-rimmed

plates and shiny silverware, the heavy burnished oak furniture and intricate

mosaics. The priests' home had an otherworldly feel. Holy.

Brzyski showered little John with the most attention, often taking him

out to fast food restaurants and movies. One night, he parked the car

behind a supermarket and reached down the boy's pants. John managed to

fight him off, but the attacks continued. Brzyski would corner him in

the sacristy as he vested for Mass, fondling him through his school trousers

and grinding up against him. John warned Brzyski that he would tell his

parents. The priest only laughed, said Delaney, and said, "Go ahead,

your mother knows full well what's going on and is perfectly fine with

it, and your dad doesn't give a shit since he's not even your real father."

One day after Mass, Brzyski took John to his room in the rectory. It was

a small room with a big bed. The walls were unadorned except for a crucifix.

The priest gave him something to drink, said Delaney, and he woke up hours

later, lying across the bed on his stomach, his pants and underwear pulled

around his knees, his shirt and sweater askew. Brzyski, 6 feet 5 inches,

220 pounds, as the grand jury report describes him, filled a small chair

in the corner, his collar undone, his brow filled with sweat. He was smiling.

"How ya feeling, boy?" he said.

John was scared. He fumbled with his clothes and left quickly. He tried

to run but it hurt to even walk. Once home, he stood in the shower for

what seemed like hours, crying, shivering, watching the bathwater swirl

with his blood and disappear down the drain.

"It ruined me," said Delaney in his interview with the prosecutor.

"It ruined me completely."

The two men talked for hours. When it was over, they shook hands and said

goodbye. The rest of Spade's day was spent in a strategy meeting with

one of his bosses. He tried his best to concentrate but, for the life

of him, could not.

* * *

In the spring of 2002, as the Catholic church sex scandal exploded across

the nation, Philadelphia District Attorney Lynn Abraham convened a grand

jury to examine how archdiocesan officials handled sexual abuse complaints

over the last half-century. A team of five prosecutors and two detectives

were handed the daunting task of investigating one of the most powerful

American archdioceses. A long, painful road lay ahead. Investigators faced

contentious church officials, attorneys and stringent statutes of limitation.

Many of the archdiocese's nearly million and a half Catholics were uneasy

about the probe. The press was largely deferential to the archdiocese.

Thousands upon thousands of church records -- that first had to be wrestled

from the archdiocese's "Secret Archive" -- had to be sifted

and sorted. Abusive priests had to be tracked down. Hundreds of victims

had to be interviewed.

Will Spade had seven years of experience at the district attorney's office

when he was assigned to the church case. But nothing, he said, could have

prepared him for the two years he would spend as part of the "God

Squad" -- as some within the district attorney's office dubbed the

investigation's prosecutorial team. Along with the other investigators,

Spade often worked up to 15 hours a day, seven days a week, interviewing

hundreds of witnesses -- victims, priests, church experts and archdiocesan

officials, including Cardinal Anthony Bevilacqua, former head of the Philadelphia

archdiocese -- helping to uncover the shocking degree to which the archdiocese

protected abusers.

During his time with the investigation, Spade would interview and prepare

for the grand jury more than 100 victims of abuse.

"It was like working in a factory," said Spade. "And in

this factory was a conveyer belt of damaged people. Every day it was another

damaged person."

The pain and anguish of the victims often became overwhelming.

"There would be times when I would come home after a particularly

bad day," said Spade, "and I would lie down on the couch with

my head in my wife's lap and cry, uncontrollably cry."

Spade developed close friendships with a number of the victims and became

the most vocal of the prosecutors arguing for indictments to be levied

against the church hierarchy. Paradoxically, he developed a unique friendship

with a former high-ranking archdiocesan priest involved in the cover-up.

The investigation also introduced him to well-known canon lawyer and Jesuit

Fr. Ladislas Orsy, as well as Dominican Fr. Thomas Doyle, the outspoken

advocate of abuse victims.

"Overall the experience reaffirmed for me the belief that power corrupts,"

said Spade. "But while sorting through all the horribleness, I also

encountered so many good and decent Catholic priests. I became drawn to

Catholicism."

He began attending Mass.

Exhausted and emotionally drained, Spade left the district attorney's

office in the fall of 2004, a year before the investigation was completed.

The grand

jury's report released in September 2005 stands as one of the most

comprehensive and scathing accounts of clerical sex abuse and cover-up

ever issued (NCR, Oct. 7). While admitting the problem of sexual abuse

of young people is a "societal evil," archdiocesan officials

blasted the report as "lopsided," "biased" and fueled

by "anti-Catholic" sentiments.

But a deeper look inside the Philadelphia investigation allows for a far

more comprehensive understanding of the church's handling of sexual abuse

complaints. It is a complex -- and often unnerving -- story that leads

deep into the murky grayness of the crosscurrents of anger and pain, betrayal

and forgiveness, hope and dismay, atonement and denial that flow through

the heart of the Catholic church's sex scandal.

* * *

A few months after the emotional Sunday afternoon with Billy, Spade

stood at the side counter of a Dunkin' Donuts located in the bowels of

Suburban Station, Philly's underground railway hub. He recalls being nervous,

checking his watch, waiting for the latest files to arrive. After rounds

of contentious legal arm-twisting, the archdiocese had agreed to hand

over to prosecutors the personnel records of accused priests, which officials

kept locked away in file cabinets in a room guarded by an alarm system

on the 12th floor of their Center City offices. About once a month, a

church attorney met Spade or another investigator with a batch of documents.

Although Bevilacqua pledged to cooperate fully with the investigation,

church attorneys balked and delayed at every possible turn, slowing proceedings

to a crawl. The foot-dragging was especially frustrating to Spade and

the other frontline investigators who spent thousands of hours combing

through the records and interviewing more than 100 victims who stepped

forward. Their tales are sadly similar and revolve around years of depression

and anger, sexual confusion and intimacy issues, or drug and alcohol abuse.

Many have failed marriages and shattered faith. One man took a razor to

his throat, slicing nearly to the jugular, and wrists, reaching the bone.

He survived and has spent much of his adulthood in and out of mental institutions.

Some of the files seemed intentionally vague, using euphemisms like "same

bed: touches" to describe incidents of rape and molestation. Others,

though, are painfully detailed and provide investigators with a blueprint

of how Bevilacqua, who led the archdiocese from 1988 to 2003, and his

predecessor, Cardinal John Krol (1961-88) routinely shuffled abusive priests

from one unsuspecting parish to the next. (One serial abuser was moved

through so many parishes -- 17 in all -- that archdiocesan officials worried

they were running out of churches where parishioners would be unaware

of his predilections.) Abusers were almost never permanently removed from

active ministry. And in almost every case, the civil authorities were

not informed of the abuse.

|

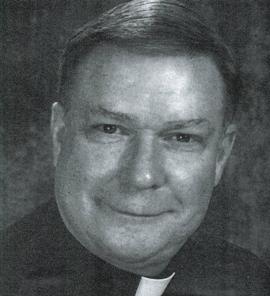

| Msgr. James Molloy |

"It was immediately obvious to us that the hierarchy were dealing

with these complaints not as caring religious people," said Spade,

"but as lawyers concerned with legal culpability. And this is ultimately

what the grand jury found."

The files prove false the archdiocese's 2002 claim of 50 credible instances

of abuse by 35 priests in the last 50 years. The actual number of alleged

abusers is closer to 200. The victims -- at least those investigators

are aware of -- total in the hundreds.

The files also contain proof that high-ranking church officials provided

abusers with possible defenses that, according to the report, "might

embarrass or discourage a victim from pressing an allegation." On

one occasion, Msgr. Bill Lynn, secretary for clergy, suggested to Fr.

Thomas Shea -- who previously admitted sexually abusing two boys -- that

perhaps he was "seduced into it" by his 10-year-old victim.

[Note: See the archdiocesan

document with this quote (PDF page 4, first paragraph), and the Philadelphia

Grand Jury Report, Section V, Selected Case Studies, Father Thomas F. Shea, which discusses the document (page 2 of the

PDF).]

"You'd read something like that and have to resort to gallows humor

just to keep from losing your mind," said Spade. "Like 'Yep,

here's another kid asking for it.' "

Investigators searched for someone within the archdiocese who could provide

context to the files.

"We wanted to sit them down like an anthropological experiment and

ask them, 'What were you thinking when you did this? What was going through

your mind when you said that?' " recalls Spade. "The experts

were telling us that we were crazy, that we'd never get anybody to explain

it honestly."

Indeed, most church officials sought -- or agreed to at the archdiocese's

urging -- legal representation from the Philadelphia law firm Stradley

Ronon Stevens & Young. One name conspicuously not on the list is Msgr.

James Molloy, who was the third-highest ranking archdiocesan official

in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It's Molloy's signature that appears

at the bottom of many of the files investigators were poring over.

* * *

Molloy left the archdiocese's central administration offices in 1993

and until his death from a heart attack in early March of this year, most

recently was the pastor of St. Agnes Parish in Sellersville, a small town

45 miles northwest of Philadelphia. It is one of the most distant parishes

to which a Philadelphia priest can be assigned and still remain within

archdiocesan boundaries (or as one priest puts it, "a quaint little

Siberia"). The modern church and small brick rectory stand just off

Sellersville's elm- and sycamore-lined North Main Street.

Molloy, at 60 a reserved-looking man with graying light brown hair and

a placid demeanor, sat in his rectory office waiting for the investigators

to arrive.

"What took you so long?" he had asked, with a nervous laugh,

when they first phoned him two days earlier.

| 'The truth is the truth,' Msgr. Molloy recalled reasoning when making

his decision to cooperate, 'and anyone who sincerely seeks out the

truth is engaged in the building of God's kingdom in some fashion.' |

Molloy had expected to be one of the first called to testify in front

of the grand jury. More surprising, he had yet to hear from the archdiocese.

He had assumed they'd want him under their legal supervision and offer

representation, but their call never came. Along with later developments,

the snub confirmed his suspicions that his superiors and their lawyers

were concerned first and foremost with protecting themselves and not the

functionaries who had carried out their orders.

Friends and confidants warned Molloy that it was foolish to be without

counsel and advised him to request a court-appointed attorney. He decided

against getting a lawyer. He had nothing to hide, no fear of telling the

truth, he said.

Molloy was confident that the records he had so dutifully kept would protect

him and would demonstrate for the court that he was never responsible

for harming any children. At worst, he thought they would paint him as

a naive underling.

He understood there were risks involved in cooperating. The archdiocese

was going to be unhappy.

"But the truth is the truth," he recalled reasoning when making

his decision to cooperate, "and anyone who sincerely seeks out the

truth is engaged in the building of God's kingdom in some fashion."

Spade and another prosecutor arrived at St. Agnes sometime before noon,

carrying documents bearing Molloy's signature. They waited in the rectory

vestibule, worried that Molloy had decided to retain a lawyer.

Molloy invited them into his office to sit down.

"How can I help you?" he asked. "What would you like to

know?"

Spade answered: "We want to know the truth of how this all happened."

* * *

The son of an oil refinery worker, Molloy grew up in East Lansdowne,

a small, working-class neighborhood in Delaware County, Pa. The parish

priests impressed him as being "pretty good guys," and he entered

St. Charles Borromeo Seminary immediately after graduating from high school

in 1964.

He was ordained by Krol.

"Do you promise respect and obedience to me and my successors?"

asked Krol, taking Molloy's hands in his, at one point in the ceremony.

"I do."

"May God, who has begun the good work in you, now bring it to fulfillment."

| Molloy said he never contemplated calling the press, alerting parishioners

or contacting authorities. 'The archbishop was still the archbishop,'

he said. 'He deserved the benefit of the doubt.' |

After some quiet years of parish work in South Philadelphia, Molloy decided

to continue his studies, earning a degree in sociology at The Catholic

University of America in Washington. Not long after returning to Philadelphia,

he was assigned to the archdiocese's Family Life Office, coordinating

marriage preparation services. He enjoyed the administrative aspects of

the assignment but had little ambition or desire to move up the central

administration ladder, he said. He wanted to return to full-time parish

work.

"I wanted a peaceful little parish somewhere," he said during

one of a half-dozen interviews with this writer, totaling close to two-dozen

hours. "And maybe one day to become a pastor."

By 1987, Krol's failing health had brought an end to his nearly three-decade

reign over the Philadelphia church. His successor, Bevilacqua, a charismatic,

conservative-minded canon lawyer and civil lawyer, immediately went about

reorganizing the archdiocese, breaking it into six regions, each overseen

by an administrator known as a vicar. Bevilacqua appointed the highly

respected Msgr. Edward Cullen as his vicar for administration. Status

reports were demanded from all department heads. Molloy suspected the

highly nuanced organizational charts included in his reports from the

Family Life Office might have been what got him appointed assistant vicar

for administration, answerable only to Cullen and Bevilacqua.

Molloy became the day-to-day operator of the archdiocese's "Central

Tower." It was his job to ensure that all administrative paperwork

heading for Bevilacqua and Cullen was "ready for primetime."

He excelled at his new position. In his first week alone, he prepared

120 memos outlining proposed construction projects.

Originally, sexual abuse complaints were processed by the Office of the

Secretariat for Clergy, which handled all priestly personnel issues. (By

canon law, the archdiocese was required to keep a written record of both

the victim's claims and the accused priest's response.) But as accusations

began to pile up in the late 1980s, the responsibility was shifted to

Molloy, he suspected, because of his administrative prowess.

"It was a matter of happenstance," he said. "They needed

someone with my talent for drudgery."

Molloy met victims in a small office on the 12th floor of the archdiocese's

Center City headquarters, which was located across the hall from the cardinal's

large office and a few doors down from the "Secret Archive"

records room. The secretary for clergy, Msgr. Bill Lynn, was also present.

One of the men would take notes while the other conducted the interview.

To avoid giving the impression that the accused priest might be guilty,

Molloy said he and Lynn were instructed not to treat complainants with

excessive sympathy or compassion.

"We were functionaries, auditors," said Molloy. "Our job

was to interview the victim and the accused priest, then write up a report

for the archbishop. We didn't have marching orders to do anything other

than that."

It was an exhausting and time-consuming job, Molloy said.

"I did all my own typing," he said. "Because of the required

confidentiality, I didn't have secretarial assistance."

All victims were offered counseling paid for by the archdiocese. "But

none of them ever came in looking for money," he said. "They

were there because they wanted the priest reported and removed."

The accused priest was called in separately -- "Most times they'd

lie and deny it," said Molloy -- and no other witnesses were interviewed.

Accused priests were sent to the archdiocesan-owned St. John Vianney Medical

Center in nearby Downingtown, where they would undergo "multidisciplinary"

evaluations. A doctor there almost always ruled out pedophilia, a finding

that, under canon law, would have required that the priest be removed

from ministry. But in nearly every case, the priest was reassigned to

a different parish.

"To determine if a priest was a pedophile," reads the grand

jury report, "the 'treatment' facility often simply asked the priest.

Not surprisingly, the priest often said no." [For this quote, see

the Philadelphia Grand Jury Report, Section III, Overview

of the Cover-Up by Archdiocese Officials, PDF page 17.]

The shuffling of abusive priests troubled Molloy from the very beginning.

"But," he wrote in one of the many e-mails this reporter exchanged

with him during the final two months of his life, "I was in no position

to question the authority of my bishop. As a canon lawyer, the cardinal

was much more knowledgeable than I when it came to the requirements of

canon law. As a civil attorney, the cardinal was much more knowledgeable

than I when it came to the requirements of civil law. And as the archbishop

he was entitled to a presumption on my part (as his subordinate of goodwill)

that he was doing the right things as best he knew how. He was, by his

office, entitled to a commitment of reverential trust on my part."

Molloy was rarely privy to the discussions concerning reassignments. (The

authority to reassign priests belonged solely to the cardinals, Krol and

Bevilacqua. Cullen acted as his consultant.) "Anyhow it would be

uncharacteristic of me to be combative to my superiors," said Molloy.

"Even if I disagreed, I did not see it as my role to make a big deal

out of it."

* * *

One of the earlier cases Molloy handled was that of Fr. Nicholas Cudemo.

Molloy would later tell the grand jury that Cudemo "was one of the

sickest people I ever knew." According to the grand jury's report,

Cudemo "raped an 11-year-old girl, molested a fifth grader in the

confessional, invoked God to seduce and shame his victims, and maintained

sexually abusive relationships simultaneously with several girls from

the Catholic school where he was a teacher." His own family sued

him for molesting a cousin. [See the Philadelphia Grand Jury Report, Section

V, Selected Case Studies, Father

Nicholas V. Cudemo, PDF page 1.]

"He exemplified all of the character traits common to pedophiles,"

recalled Molloy. "He was egocentric, narcissistic, histrionic, impulsive

and lacked self-control. He annoyed me very much. I couldn't understand

why he was being given such latitude."

Cudemo already had numerous allegations and subsequent reassignments on

his record. Molloy told the latest victim that although he still had to

talk with Cudemo, he had "no reason not" to believe her. He

assured the victim the cardinal would suspend Cudemo if he contacted her

family. Upon learning of his remarks, Molloy said, Cullen verbally reprimanded

him for "overreaching."

(According to the grand jury report, Cullen, who is now bishop of Allentown,

Pa., told Molloy "never to tell victims that he believed them."

The report continues, "Doing so would have made evident the church

official's knowledge of other criminal acts and made later denials difficult.")

[For this quote, see the Philadelphia Grand Jury Report, Section III, Overview

of the Cover-Up by Archdiocese Officials, PDF page 13.]

Cudemo was ordered to report to St. John Vianney Hospital for an evaluation.

"But he balked at having to go," recalled Molloy. "He was

worried that if he went other priests would know that something was wrong."

The archdiocese consented to his protests and agreed to send him to Saint

Luke's Hospital in Maryland, where he was diagnosed as a pedophile. The

doctors thought Cudemo had probably committed more abuse than he was admitting

and, in all likelihood, would continue to abuse.

"Of course Cudemo was very unhappy with this diagnosis," said

Molloy. "So, he asks for a second opinion conducted by a psychiatrist

of his own choosing."

Again, the archdiocese consented.

"And wouldn't you know," said Molloy, "this new doctor

came back with a much sunnier diagnosis."

Bevilacqua allowed Cudemo to remain in active ministry.

Cudemo was eventually removed from his pastorate after a victim threatened

to file a lawsuit. When the lawsuit was dropped, Bevilacqua gave Cudemo

a celebret, which declared him "a retired priest in good standing

in the archdiocese of Philadelphia." A celebret, which attests to

the bearer's being free of canonical censure, is needed to gain permission

to say Mass in another diocese.

"The Cudemo case was when I truly realized that I couldn't be sure

that I could trust my superiors to do the right thing," said Molloy.

"So I decided to operate in a manner that would eliminate the need

to trust anybody."

Molloy said he then went into "hyper-documentation" mode, taking

great pains to make his files to Bevilacqua and Cullen as detailed as

possible.

At the time, he said, it was the best contribution he felt he could make

to the situation, to history. If it all blew up one day -- and he was

pretty confident it would -- he wanted as detailed a record as possible

to exist. If his superiors were making the correct decisions in handling

the abusers, they would be happy to have his reports. If his superiors

were making the incorrect decisions, then his reports would help explain

what went wrong.

"I wanted my memos to be there," he said, "if the archdiocese's

decisions were eventually put on the judicial scales."

He was also motivated by self-protection.

"This way anyone could come along in the future and say this was

right or this wrong," said Molloy. "But they could never say

it wasn't all written down. No one could ever say I shaded or hid any

info."

Molloy said he never contemplated calling the press, alerting parishioners

or contacting the authorities.

"The archbishop was still the archbishop," he said. "He

deserved the benefit of the doubt."

One of the final cases Molloy handled was that of Fr. Stanley Gana. Ordained

in 1970, he was one of the most prolific abusers detailed in the grand

jury's report. "Fr. Gana sexually abused countless boys in a succession

of Philadelphia archdiocesan parishes," reads the report. "He

was known to kiss, fondle, anally sodomize, and impose oral sex on his

victims." [The first quote is from the Philadelphia Grand Jury Report,

Section II, Overview of the Sexual Abuse by Archdiocese Priests, Pattern

Study of Father Stanley Gana. The second quote is from Section V,

Selected Case Studies, Father Stanley Gana, PDF page 1. See also the Philadelphia

Grand Jury Report's materials on Gana.]

Two of Gana's victims informed the archdiocese of their abuse in the early

1990s. At around the same time, Molloy said, he was ordered to investigate

a young seminarian that was believed to be engaging in homosexual relationships.

The seminarian told Molloy that Gana had abused him as a child for five

years beginning when he was 13 years old. The seminarian provided the

names of two other boys whom Gana had also molested. In filing his report

to Bevilacqua, Molloy strayed from his usual recitation of the facts and

injected his own bit of advice, suggesting to the cardinal that a "forensic

psychiatrist" examine Gana. In Molloy's eyes, offering this common

sense suggestion was some type of bold, defiant course of action. He was,

he said, a "frustrated messenger."

"By suggesting a forensic psychiatrist, I was saying this is serious

business," said Molloy. "That this man could still be abusing

kids and should be investigated by the authorities."

Molloy's advice was ignored. The seminarian was expelled from the seminary.

According to the report, archdiocesan officials instructed Gana to keep

a "low profile." [See Philadelphia Grand Jury Report, Section

V, Selected Case Studies, Father Stanley Gana, PDF page 21.] He was allowed to remain in active

ministry. For his part, Molloy was informed that he was being reassigned

from central administration. He had not requested a reassignment -- to

do so, he said, would have been openly insubordinate and disrespectful

of the bishop -- but he was grateful to be leaving his post. The secrecy

surrounding the complaints had become too much for him. "It had gotten

to the point where I felt like I was working for the CIA instead of the

church," he said.

|

| Cardinal Anthony J. Bevilacqua, retired

archbishop of Philadelphia, in 2003. Photo by CNS / Nancy Wiehec. |

He suspected his new position at St. Charles Borromeo Seminary, where

he was rector from 1994 to 1999, resulted from his superior's displeasure

with his handling of the Gana case. "Was I the best man for the job?"

he asked of his reassignment. "Or were they getting uncomfortable

with how I was doing things? I don't know."

In his final act as assistant vicar for administration, Molloy requested

the alarm code to the records room be reprogrammed and that all the locks

and combinations to the filing cabinets and safes be changed. He wanted

to make sure no one could ever accuse him of coming back to steal or alter

the reports he had written.

"I washed my hands of the place," he said, "and just prayed

and tried to have faith that they'd do the right thing in future cases."

* * *

The grand jury met twice a week in the top-floor conference room of

a gray, modern Center City office building, two blocks from where the

spire of the Basilica of Sts. Peter and Paul rises into the sky. The conference

room was wide with high ceilings. Jurors sat in rows of chairs positioned

in front of windows offering a view of North Philadelphia.

Aquilla Allen, a quiet, soft-spoken white-haired grandmother from Southwest

Philadelphia, usually sat in the first row. Allen was baptized Catholic

and attended St. Agatha in West Philadelphia until her mother passed away

and her aunt began taking her to Methodist services. As an adult, she

married a Baptist and remained Protestant. But she always held fond memories

of her Catholic upbringing.

| Juror Aquilla Allen was shocked that the archdiocese didn't conduct

more serious investigations when allegations arose. Most times, if

the accused priest denied what happened, that was good enough for

the archdiocese. |

She was filled with a certain amount of skepticism when the judge informed

the jury that they had been selected to hear evidence of a sexual abuse

cover-up within the church. The news reports of the scandals made her

uneasy. She could accept there were some problem priests but she had a

hard time believing that the church would orchestrate a full-scale cover-up.

The victims sat at a long table facing the jurors.

Allen and the other jurors were often reduced to tears.

Alfred Roberts, a thin man with angular cheekbones, was the sole black

victim to testify. He spoke in a trembling voice and shook and cried while

he testified. "You know you're the only colored altar boy, Alfred,"

he said the priest who repeatedly raped him had warned, "and that's

a privilege for you and your family. You don't want to embarrass your

family and start any trouble. No one would believe a colored boy talking

about a priest anyway."

There is John Delaney, who explained how the priest who began raping him

when he was 10 years old made him believe that his own mother consented

to the abuse.

"I've harbored this feeling toward my mom for going on 20 years,"

Delaney testified, "only to come to find out the other night that

it wasn't true. She had no idea. She had absolutely no idea. I've been

hating her for 20 years for no reason whatsoever, and that's not right.

That's my mom."

Spade, the assistant district attorney, asked Delaney why he allowed the

priest to have sex with him even as he grew into his older teenage years.

Delaney paused for a long moment. "I don't know," he said, "I

don't know." Everyone cried during his testimony. Even Spade.

Some of the testimony is so shocking Allen wishes she could forget it

as quickly as she heard it.

"These were just babies, 9 or 10 years old," said Allen. "And

to think they had to live with the fear of this happening day after day

and not knowing if it would ever end. It was heartbreaking."

As terrible as the stories of abuse were, Allen reasons that if you pulled

the roof off of any organized church, you'd find sick, perverted individuals

abusing their power. What shocks her most is how the leaders hid everything.

"In the beginning, I didn't want to think that this could ever happen,"

she said. "But after hearing all this testimony, you almost started

to believe that abusive priests would alert other abusers and let them

know they could come into the Catholic church and be protected."

Allen was shocked that the archdiocese didn't conduct more serious investigations

when allegations arose. Most times, if the accused priest denied what

happened, that was good enough for the archdiocese.

"They were feeding these kids to the wolves," she said.

Jurors were not allowed to directly question witnesses. Rather, they submitted

their queries orally to prosecutors who then posed the questions to the

witnesses. Allen regularly found herself holding onto her seat and biting

her tongue during cross-examinations of church officials.

| 'I was learning about canon law and the rituals and history and

tenets of the Catholic faith,' Spade said. 'And I found myself being

drawn into it.' He began attending Mass. |

Lynn, the secretary for clergy, testified to why Gana was allowed to

remain in active ministry, even after a young seminarian and two other

men accused him of abuse. Gana, Lynn explained, was not only having sex

with children. He was also sleeping with women, abusing alcohol and stealing

church property. "You see," said Lynn, "he was not a pure

pedophile. Otherwise he would have been removed." [For the first

half of this quote, see the Philadelphia Grand Jury Report, Section V,

Selected Case Studies, Father Stanley Gana, PDF page 1.]

When asked why the archdiocese did not follow up on further accusations

of abuse against Gana, Lynn replied, coolly, "It must have fallen

through the cracks."

"We all just gasped at that," remembered Allen. "It was

sickening."

Allen recalled Bevilacqua as "arrogant and cocky" during his

testimony. "He would ignore every question and answer with the same

refrain of 'Our main concern was the safety of the children.' It was angering

because it was obvious that his main concern was protecting his priests

and the church."

Bevilacqua testified in front of the grand jury a total of 11 times. "You

could tell how annoyed he was at having to be there," said Allen.

"His tone, his mannerisms, they never changed. He was always cold.

And every time it was the same thing of 'I'm the cardinal and I'm telling

you our main concern was for the children.' "

Allen wondered how someone could be in a position of power all those years

and never do anything to stop the evil being committed against those children.

"In the end," she said with a sigh, "I guess he knew that

regardless of what he did he'd always have people supporting him."

* * *

Spade sat at the prosecutor's table, listening as another attorney asked

Lynn to identify for the grand jury a batch of documents detailing the

transfers of dozens of abusive priests. It was as if the courtroom had

become an arena for the unimaginable. Fr. Nilos Martins, who in the mid-1980s

was the assistant pastor of Incarnation of Our Lord in North Philadelphia,

invited a 12-year-old boy, Daniel, up to his rectory room one Saturday

afternoon to watch television. The priest ordered the child to undress

and then anally raped him. Spade listened as Daniel, now a Philadelphia

police officer, testified that as he cried out in pain, the priest kept

insisting, "Tell me that you like it." When the priest was done,

he gave Daniel a puzzle as a present and told the boy to get dressed and

leave.

|

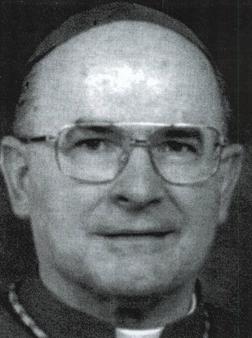

| Bishop Edward P. Cullen, who now heads

the Allentown, Pa., diocese. Photo by CNS. |

A few days later, Daniel returned to the church to serve Mass as an altar

boy. The pastor, Fr. John Shelley, had learned of the attack from a teacher

Daniel confided in. He informed Daniel that he was no longer welcome as

an altar boy. Word of the attack then spread through the parish school.

According to his testimony, one of Daniel's teachers, a Sr. Mary Loyola,

began to refer to him as Daniella, prompting laughter from the rest of

the class. When Daniel begged his teacher to stop, she gave him a demerit.

[See the Philadelphia Grand Jury Report, Section II, Overview of the Sexual

Abuse by Archdiocese Priests, Pattern

Study of Father Nilo Martins.]

"I can't be sitting here listening to this," thought Spade.

"I must be imagining what I'm hearing."

The names of the victim and Sr. Mary Loyola were changed for the report.

The investigation was taking a toll on Spade. One of his best strengths

as a prosecutor, he said, was that he had always been comfortable dwelling

in the extreme emotions that typify a criminal case. But the procession

of shattered victims was becoming overwhelming.

"Every day you were either talking to a victim on the phone or having

a victim come into the office or putting a victim through the grand jury,"

he said in an interview. "Most of them were men, and seeing a grown

man cry really shakes you up."

During that period, if he was not at the office, he was interviewing a

victim or witness. If he was not working on the case, he was thinking

about it, obsessing about it. He was depressed, moody, and distant to

his wife, who was unable to share his experiences due to confidentiality

constraints.

"The emotions of the investigation became a raw wound," he said.

"It was always there, festering."

He found himself becoming overprotective and paranoid about his own children's

safety. "I was dealing with all these cases where kids were betrayed

by those they were taught to trust the most," he said. "I was

like, 'My God, you can't trust your children with your friends, teachers,

or even other family members.' I don't think it's healthy to be like that."

From the very beginning of the investigation, public relations spokespersons

connected to the archdiocese condemned the probe as an anti-Catholic witch-hunt.

The Catholic-bashing talk became a running joke among investigators. Three

of the five frontline investigators were Catholic.

"I was raised Catholic," said former prosecutor Maureen McCartney.

"I had 12 years of Catholic school. My family is very Catholic. It

is a big part of my life. This was never an anti-Catholic project. It

was just something that needed to be done."

McCartney, who had two-and-a-half years experience in the district attorney's

family violence/sexual assaults unit before joining the church probe,

said separating her personal faith from the failings of the institution

helped her get through the investigation.

"It was never my nature to look at a priest and say, 'Wow! You're

perfect,' " she said. "I wasn't shocked to learn that they're

fallible."

Spade was impressed with how his fellow investigators hung on to their

faith. "These were people I liked and respected very much,"

he said. "And it was compelling for me to see how despite all the

horrible stuff we were encountering, their belief in this institution,

their belief in this faith, was still so very important to them."

Spade grew up attending weekly services at the Lutheran church, Sunday

school and the altar boy guild. He fell away from his faith during college

but as a young lawyer living in Philadelphia, he began attending St. Mark's

Episcopal Church.

"I was always very analytical about my faith," said Spade, "and

I would sit and think about what is God. What exactly is God? How do you

know there is a God? I used to play with that a lot but I always ended

up believing."

The investigation allowed Spade an opportunity to meet the noted Jesuit

canon lawyer Ladislas Orsy. Along with two other investigators, Spade

drove to Washington, where Orsy is a professor at Georgetown University.

Over lunch, the Jesuit delivered a long discourse on how the general attitude

of the Vatican, as well as the local hierarchy in Philadelphia, was to

save the "institution" from scandal while the biblical precept

to protect children went largely ignored.

Orsy quoted Jesus in the New Testament: "If anyone causes one of

these little ones who believe in me to sin, it would be better for him

to have a large millstone hung around his neck and to be drowned in the

depths of the sea." He spoke fondly of the time of the Second Vatican

Council when "we were talking about reform of the church all day

and all night, in churches, in schools, in sidewalk cafes."

The investigators spent the better part of day with Orsy. Spade would

also work closely with Fr. Thomas Doyle, an advocate for clergy abuse

victims, and many other "good and decent, hardworking" Catholic

priests.

"I was learning about canon law and the rituals and history and tenets

of the Catholic faith," he said. "And I found myself being drawn

to it."

He began attending Mass.

Spade would discuss his feelings with his wife, Karen, a lapsed Catholic.

"I would tell her how I really liked the faith and she would say,

'Are you out of your mind? You're seeing what this institution has done

to these kids and you're saying you like it?' And I'd say, 'No, I don't

like the institution but I like the faith, I like the intellectual and

spiritual part of it.'

"It's funny," he continues. "We were all being bashed as

being anti-Catholic and here I was defending the church to my own wife,

who was Catholic."

* * *

It is springtime, early morning. Spade and Molloy drive along the suburban

sprawl and roadside towns leading from the village of Sellersville to

Philadelphia. Today, Molloy will testify in front of the grand jury. Working

closely together, the two men have struck up a friendship.

They make small talk as they drive.

"Are you nervous?" asks Spade.

"Not as nervous as my brain is telling me I should be."

"I understand the risk you're taking."

"But like I always tell people when they're facing a tough decision,"

says Molloy. "Jesus didn't get up on the cross on Good Friday because

he didn't have anything better to do. He did it because it was the right

thing to do."

Once, while going over old documents, Spade had asked him, "Father,

you're such a nice guy, how could you have been a part of this? I mean

you had to know what you were doing was wrong."

"He didn't have any real answer," recalls Spade, "other

that it was his job and that he was trained to be obedient to his cardinal."

When it is all done, when the report is finally released, a single sentence

on Page 41 will distinguish Molloy from others who participated in the

handling of the complaints. It reads, "Molloy displayed glimpses

of compassion for victims." The local press will not make such distinctions.

Articles will be written labeling him an "enabler" of abuse.

He will receive hate mail from people who read those articles. [For the

exact quote from the report, see Philadelphia Grand Jury Report, Section

III, Overview

of the Cover-Up by Archdiocese Officials (PDF page 13).]

Molloy was unhappy with the final report.

"Overall, it is accurate in that it captures the failures of the

institution in ensuring the welfare and safety of children," he said.

"But it left out parts of the story, parts of the context that would

allow someone a full understanding of what happened."

The report makes no mention of Molloy's uneasiness with the reassignments

or his suggestions for using a "forensic psychiatrist."

It also makes no mention, he said, that in many cases, the archdiocese

was honoring victims' requests for confidentiality by not contacting the

authorities or alerting parishioners. He emphasized that in all cases,

Bevilacqua had abusive priests undergo multidisciplinary evaluations.

"In most instances, the report would rule out pedophilia," he

said. "So, you're the archbishop and you have a report of abuse occurring,

say 12 years ago. There are no recent allegations of abuse. Pedophilia

has been ruled out. What do you do with the guy? Do you send him back?

All these things are debatable. I myself would not have sent some of them

back into ministry. I would be paranoid about taking a chance like that.

However, it's not as if the archbishop was acting arbitrarily. He had

a basis for making these decisions. In retrospect a lot of people disagreed

with the basis he used for his decisions. But it was probably state of

the art for its time."

He believes the scathing tone of the report was due to the investigators'

anger over the archdiocesan attorney's "hardball tactics."

"I look back and say what happened was insufficiently protective

of the welfare of children," Molloy said. "But I don't want

to say there was a lot of badly motivated men trying to conspire to achieve

a cover-up."

As for his own regrets, he said, he wished he had shown more compassion,

offered more assistance to the victims he encountered.

"I regret that very much," he said. "More than anything."

He said he sat down numerous times to write letters offering assistance

to John Salveson, the president of the Philadelphia Survivors Network

of those Abused by Priests, SNAP.

He said he wanted Salveson to know he would meet with the victims with

whom he had had contact "to try to answer any questions they had

about the way things had developed in the diocese with their cases."

But he never finished the letters.

"I had to hesitate in the end because there is the possibility of

lawsuits being filed down the road, and I did not want to create a situation

which would be construed as an attempt to manipulate people's opinion."

In the aftermath of the report and the media articles, Molloy held a town

hall meeting at St. Agnes, giving parishioners a chance to ask him any

questions or voice concerns. He also took the initiative to meet with

two parish families who had relatives who were sexually abused.

At the time of the interviews with this writer, which occurred during

the final three months of Molloy's life, he said attendance at St. Agnes

was strong and collections were increasing. "People have been supportive

and understanding."

"After all," he said. "I wasn't the one making the decisions.

I was just a frustrated messenger."

Would he have done anything differently?

"I suppose that I would like to think that there could have been

more insistence on my part that some of these perps could have been dealt

with more severely." Or maybe, he said, "I would find some polite

way of convincing the archbishop that it would not be good for me to accept

appointment to a position in such an office of the central administration."

But in the end, he said, "My job now is the same as it was then.

To do the assignments I get from my bishop to the best of my ability."

* * *

On March 7, a cold, cloudy Tuesday, Molloy returned to the St. Agnes

rectory office after visiting patients at a local hospital. He spent a

few minutes joking with the secretary and then, at around 4:15, headed

back to his room to take a quick nap before the 5:15 Mass. He never showed

up at the church. He was found sitting up in his bed. Both his parents

suffered with heart problems and his family believes he died from a heart

attack.

A memorial Mass was held at St. Agnes, attended by Cardinal Justin Rigali,

Bevilacqua's successor, the archdiocese's six auxiliary bishops and hundreds

of priests and parishioners. Fr. Stephen Dougherty, a friend of Molloy's

dating back 40 years to the seminary, was the homilist. He began his homily

by reciting Molloy's own words from an invitation to worship posted on

St. Agnes' Web site. "Come into this house and bring all you are,"

Molloy had written. "No need to check your failures at the door.

They are no perfect people here. You are invited, so come. Come in seeking,

come in wandering, come in hurting. Come into this house of companionship

and compassion. Come in. You are welcome here."

At the end of Mass, Rigali spoke briefly, offering condolences to Molloy's

family and remembering him as a good man and a dedicated priest. No mention

was made of Molloy's cooperation with the grand jury investigators.

"I'm disappointed nothing was said about it," Spade said after

the funeral. "After talking with Molloy for a long time, I believe

he was a good and decent man who was a product of the church he had committed

his life to. I think he realized mistakes had been made and would have

liked people to know that he helped get the truth out."

* * *

On a recent Sunday afternoon, Spade sat in his living room and read

for me a personal note he had scribbled on a yellow legal pad after a

particularly long and agonizing day just a few months into the investigation.

"I'm beginning to believe it [the investigation] will amount to nothing

more than just a scathing report which will set out in detail the way

the archdiocese through Krol and Bevilacqua allowed child abusers to continually

abuse children without removing them from their ministries."

"Prophetic, huh?" he asks now.

It was apparent to investigators almost from the start that they would

most likely not be able to prosecute the hierarchy for the cover-up. Pennsylvania's

statutes of limitations -- among the most stringent in the country --

protected archdiocesan officials from prosecution. Experts agree that

most child abuse victims repress their memories of the abuse for decades

before reporting it. But until 2002, a victim of child abuse in Pennsylvania

had only two years after their 18th birthday to file charges. After the

clergy abuse scandal broke nationwide, the statutes were extended to a

victim's 30th birthday. Still, time had expired in all but one of the

cases investigators were examining.

There was also another major obstacle to prosecution. Because of the way

the archdiocese is set up legally, as an "unincorporated association"

rather than a corporation, investigators realized that a loophole in Pennsylvania

law most likely protected church officials from being prosecuted for crimes

such as endangering the welfare of children, intimidation of victims and

witnesses, and obstruction of justice. In short, Pennsylvania law did

not seem to hold Bevilacqua or other church officials responsible for

"the supervision of children." Only the individual priests who

committed the abuse could be prosecuted, but they were almost all protected

under the statutes of limitations.

"What the hierarchy had done should have been a crime," said

Spade. "But there were no legal precedents that allowed us to hold

them responsible for endangering the welfare of children."

Division developed within the district attorney's office on how to proceed.

Some believed the office should indict Bevilacqua and other church officials

in the hope of creating new precedent. Others within the office viewed

indictments as irresponsible and unlikely to succeed, given the narrowly

defined laws. They feared failed indictments would tie the investigation

up for years, which would delay them from releasing a detailed report,

create sympathy for church officials, and open the office up to even more

accusations of Catholic-bashing than the archdiocese was already hurling

at them.

| Although a report could document the cover-up, Spade felt a public

trial could bring more awareness to the issue of clergy sex abuse.

'My argument was let the public see the pain of the victims.' |

"That's where we had arguments," said Spade. "On whether

or not we should try and push the envelope."

Spade was among the most vocal calling for indictments.

"We were in a situation where we all believed the law was wrong,"

he said. "And I felt we had an opportunity to persuade the court

to make new law. I thought we should present the evidence and let a judge

decide."

Although a report could document the cover-up, Spade felt a public trial

could bring more awareness to the issue of clergy sex abuse.

"My argument was let the public see the pain of the victims,"

he said. "Let the public hear the ridiculous explanations from church

officials on why they didn't report abuse. Let the cardinal, the head

of the Philadelphia church, take the stand and argue that he was not responsible

for the safety of children."

"We all wanted to go after them every way possible," adds investigator

Maureen McCartney. "But our job was to look at the law and see if

these horrific crimes could be prosecuted. Sadly, the law was grossly

inadequate."

As times passes, Spade said he can now see both sides of the argument.

"I was immersed in the pain and suffering of the victims," he

said. "I was arguing with my heart."

He has remained friends with John Delaney and the McDonnell brothers,

John, Brian and Alex, and they have told him that the report has helped

in their healing process. He plans to join efforts to lobby state legislators

to ban statutes of limitations in child sexual abuse cases.

"When someone is harmed, there should be retribution," he said.

"I thought that's why we have a legal system."

He still occasionally attends Catholic Mass and he and his wife have decided

to send their children to a Catholic grade school in the Philadelphia

suburbs run by the Sisters of Mercy but not directly associated with the

archdiocese.

"That was important to us," said Spade. "We liked the ideal

of service and charity that the sisters instill in the children, but we

did not want any school that was actually run by archdiocese officials."

[Michael Newall is a freelance writer working in Philadelphia.]

A Reporter Gets behind the Scenes

in Philadelphia

About this story

Reporter Mike Newall of Philadelphia spent months interviewing, rechecking

information and corroborating the recollections of those he interviewed

with details in the Philadelphia grand jury report released Sept. 21.

What resulted is a highly detailed behind-the-scenes look at the culture

in which the sex abuse scandal and its cover-up was carried out in the

Catholic church. While there are elements of the story that are distinctive,

certainly, to Philadelphia, the attitude of church officials depicted

here was hardly peculiar to a single diocese or chancery office.

I asked Newalf to provide a brief rundown on the principals he interviewed

and the amount of time he spent with them.

- Tom Roberts, editor

Prosecutors

Will Spade: During a five-month period from October 2005 to March 2006,

I interviewed Spade in person nearly a dozen times. Our interviews would

usually last two to three hours. There were too many follow-up phone calls

and email exchanges to catalogue. I also interviewed Spade’s wife.

Maureen McCartney: twice, in person, for a total of about three hours.

Jurors

Aquilla Allen: once, in person, for two hours

Jerry Corrento: once, in person, for one hour

Victims

John Delaney: once, in person, for about two hours. In addition, I spoke

to him in numerous follow-up phone calls. I was able to corroborate John’s

story with information from the grand jury report.

The McDonnell brothers: I interviewed John, Brian and Alex McDonnell

each numerous times for a story I wrote for the Philadelphia Weekly in 2004. I also interviewed John McDonnell

specifically for this story, over the phone, for about 30 minutes. Their

stories were all corroborated by the grand jury report.

Alfred Roberts: I interviewed him once in person in the spring of 2004

for about three hours, followed by numerous phone calls. Alfred was not

specifically interviewed for this story. His story was corroborated by

the grand jury report.

Msgr. James Molloy

I first interviewed Msgr. Molloy over the phone twice, in October 2005,

for a total of an hour. I then visited him at his rectory twice in January

2005. On those occasions, we talked for a total of about seven hours.

We continued our conversation with numerous phone calls and lengthy e-mail

exchanges. I talked to him a few weeks before he died. He said he was

happy his side of the story was being told.

[Note about this Web version: The text is from the National

Catholic Reporter Web site, at the URL provided at the top of this page.

The section "A reporter gets behind the scenes in Philadelphia"

was not included in the NCR Web version, but it was included in the printed

copy of the newspaper, enclosed in a box at the bottom of the second page

of the article (page 6 of the paper). BishopAccountability.org typed this

section for inclusion here. The photographs, which do not appear in the

NCR Web version, were scanned by BishopAccountability.org from the hardcopy

of the newspaper. The boxed excerpts from the article were typed by BishopAccountability.org

to suggest the layout of the original article, where they are set in display

type in the outer margin of each page but the first. We also increased

the point size of the asterisks that separate the article into sections.

Links to related NCR articles, to the Philadelphia Weekly article by Newall,

and to the Philadelphia grand jury report were added to this Web version

by BishopAccountability.org.] |