Victims' mothers say Larson should remain in prison

By Chris Strunk

Newton Kansan

July 24, 2004

http://thekansan.com/stories/072404/

Janet Patterson will spend the rest of her life advocating for the rights

of sex abuse victims. And she hopes a former Catholic priest who, she

said, drove her son to suicide will spend the next two years behind bars.

Robert Larson, convicted in 2001 of fondling altar boys at St. Mary's Catholic Church in Newton 20 years ago, is eligible for parole in September.

|

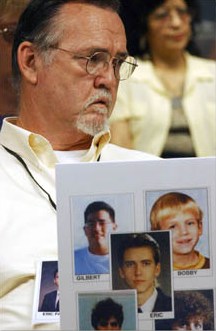

| During the parole board's public comment session in 2002, Horace Patterson holds the photos of five former altar boys whose families say committed suicide as a result of Robert Larson's abuse. Medford Logsdon / Newton Kansan. |

The Kansas Parole Board will have a public comment hearing from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. Friday at the Finney State Office Building in Wichita before making its decision next month.

"He will always be a danger, and he needs to serve the full sentence," Patterson said. "It was as harsh of a sentence as it could be for what he pled to and what he was held accountable for. But compared to the accumulative effect his actions had, this is minimal."

|

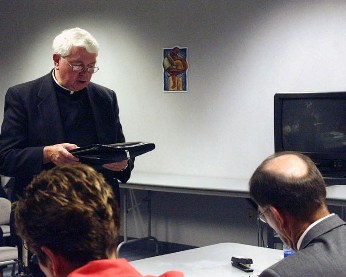

| Monsignor Charles Reagan pleads on behalf of Robert Larson in 2002 at a parole hearing. |

Larson pleaded guilty in Harvey County District Court in February 2001 to one count of felony indecent liberties with a child and three counts of misdemeanor sexual battery.

Larson was sentenced in March 2001 to 3 to 10 years prison. After serving half of the minimum sentence, Larson was denied parole by the Kansas Parole Board in 2002 because of "the serious nature and the circumstances of the crime and the objections regarding parole," the board said.

The nature of the crimes also caused the board to extend to this year Larson's second parole eligibility.

Regardless of how his second parole hearing turns out, Larson will be conditionally released from prison under supervision in March 2006.

|

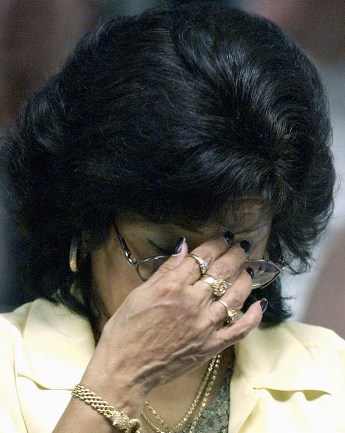

| Rachel Rodriguez mother of Gilbert Rodriguez and aunt of Paul Tafolla. |

Larson spent 30 years as a priest in the Wichita Catholic Diocese. The offenses for which he was convicted took place in the 1980s, while he was a pastor at St. Mary's. He was removed from the parish in 1988 for what Eugene Gerber, then the bishop of the diocese, acknowledged were several allegations of sexual abuse. Larson was sent to an institution in Maryland for treatment. He was eventually stripped of his title and responsibilities as a priest.

|

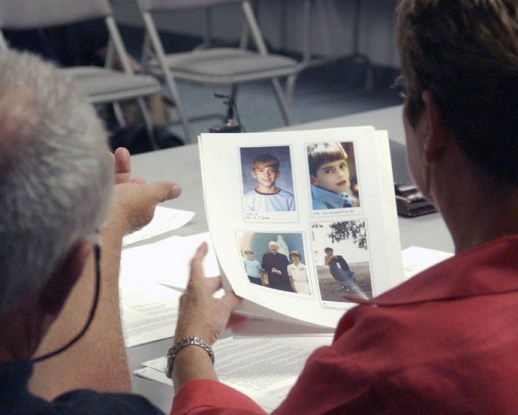

| Parole board looking at photos of the victims. |

Larson was retired and living in Willoughby, Ohio, when the charges were brought against him in Harvey County District Court.

Since Larson's conviction, several incidents of priest sexual abuse across the country have come to light, creating a firestorm of reaction from the church and from victims.

Decision in Dallas

Catholic bishops gathered in Dallas in 2002 to discuss the widespread problem and decide how far the church should go in punishing clergy who molest children.

What resulted was a "Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People," approved by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. The conference also established the Office of Child and Youth Protection to oversee the implementation of the charter.

|

| Paul Schwartz stares back at nuns speaking about how good Larson was during a parole board hearing in 2002. |

"The damage caused by sexual abuse of minors is devastating and

long-lasting," the charter reads. "We reach out to those who

suffer, but especially to the victims of sexual abuse and their families.

We apologize to them for the grave harm that has been inflicted upon them,

and we offer them our help for the future. In the light of so much suffering,

healing and reconciliation are beyond human capacity alone."

The charter calls for dioceses to:

- Reach out to victims of sexual abuse and their families in an attempt at "healing and reconciliation," including counseling, spiritual assistance, support group and other social services.

- Have mechanisms in place to respond to allegations, including a review board made up of primarily lay Catholics. The board will advise the diocesan bishop in his decisions.

- Avoid confidential agreements with victims.

- Report allegations to public authorities and cooperate with investigations.

- Remove the accused from his ministerial duties if a preliminary investigation warrants it.

- Permanently remove the accused from ministry if an investigation establishes an act of sexual abuse of a minor, past or present.

Last year, the Wichita Catholic Diocese produced updated codes of conduct for church volunteers and clergy.

The diocese also released in 2003 a revised policy on suspected abuse of children, which diocese Bishop Thomas J. Olmstead called an extension of a 1992 policy.

"We as a diocese will work with parents, educators, civil authorities and various organizations in the community to provide the safest possible environment for minors," Olmstead said in the policy.

According to the policy, priests are removed permanently from the ministry if sexual abuse is admitted or established.

|

| Eric Patterson's mother Janet listens to testimony during the 2002 parole board hearing. |

The policy also calls for educational and preventative measures, such

as background checks on potential diocesan priests, volunteers and employees.

The policy implements a "Safe Environment Program" to prevent,

identify and respond to abuse.

"The Catholic Diocese of Wichita will have as its primary concern the alleged victim's safety and well being," the policy states. "We will be committed to pastoral care for the alleged victim, the family, the accused and the congregation."

Not enough

Patterson said the diocese policy doesn't go far enough in helping victims recover.

She said the diocese should:

- Make public the names of known perpetrators within the diocese. Because of statute of limitations involved in abuse cases, many past incidents will never be made known, Patterson said.

- Publish support group news in the diocese's paper.

- Accept and publish occasional letters written about the issue of abuse.

- Require the Review Board, during its investigation of allegations, to meet with those making accusations against priests.

- Devote funds for victim recovery services, such as education, job counseling, therapy, medications and relationship counseling.

"We have made a start, and the public consciousness has finally been pierced," Patterson said. "... But we're not satisfied with the church's response to victims past and present. There are too many hoops to go through for a person grappling with this. And they're not given the resources. Whatever the church does, it should consider whether the action will help or hurt. We need to have that as our yardstick.

"I don't want anyone else to go through what my family went through," she said. "And if they do, they shouldn't have to go through it alone."

The aftermath

Patterson's son, Eric, shot himself in 1999, years after he was molested by Larson while the priest served the Pattersons' church in Conway Springs, Patterson said.

The charges for which Larson was convicted, however, involve four former Newton altar boys.

"I want to emphasize that if we can speak out, we can become survivors," Patterson said. "That's the goal for all of us, to be able to take back our lives. ... Eric survived in a very real way. I believe Eric is unlocking so many doors in our efforts to force accountability and support survivors. I'd love to see more and more families involved."

Patterson, the Kansas spokesperson for the advocacy group Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (known as SNAP), plans to speak at the public comment hearing Friday.

So will Rachel Rodriguez of Newton.

Rodriguez said her son, Gilbert Rodriguez, and nephew, Paul Tafolla, killed themselves because of the suffering Larson caused when the two served as altar boys.

Larson's sentence "is not enough time," Rodriguez said. "You know, someday he's going to walk out and have a life. And that bothers me. I feel like the pain I have is going to be there for the rest of my life."

Rodriguez said not a day goes by when she doesn't think about her son and the pain he suffered that would drive him to suicide.

She tries to push away the anger she has for Larson, Rodriguez said. It's hard.

"I live with this every day, and I will for the rest of my life. And it's just so painful," she said. "I wrote (Larson) a letter once, and he didn't respond. I was hoping that he would at least say something as a man of the cloth, something comforting, something that would show me that he made mistakes and was sorry for them. But he never responded to that letter."

Seeking closure

Rodriguez said she has not attended the Catholic Church for some time. She wants to. She just can't bring herself to go. It's too painful, she said. She doesn't want to think about the dedication her son had for his faith. And the horrible things that happened to him.

"I was hoping ever since it started that there would be closure; that there would be something said or done that would give me comfort," she said. "... I would love to go to Mass again. I'm looking forward to that day."

Rodriguez said she would like to ask Catholic officials questions about the church's policies and the past abuse. She wants to know why allegations against Larson weren't acted on long ago. She wants an apology.

"This will never be over for me," she said. "I still struggle every day. I still think about it every day."

Darren Razor, also a former altar boy in Newton, said he has suffered bouts of depression as an adult. Razor and Paul Schwartz, who lives near Kansas City, were two of the four boys Larson admitted to molesting.

"I'm going to deal with it the rest of my life," Razor said in 2002. "Eighteen months (of prison time) is nothing."

But Larson had his supporters at the 2002 hearing.

"A lot of what has been said up here has been stretched," Angela Burger, who worked with Larson in serving the needy in Wichita during the 1970s, said during the 2002 hearing. "Father Larson was a good man. ... I watched him work tirelessly for thousands of people. ... We're holding a man in prison who can be outside doing good. This man is a good to society. ... I beg and plead that we show forgiveness."

Priests also supported Larson.

"We don't come in any way to condone or excuse any crime," said retired Monsignor Charles Reagan. "We simply make a plea for mercy in his parole. ... He has shown that he is deeply sorry for having offended God, bishops, his fellow priests and all Catholics."

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.